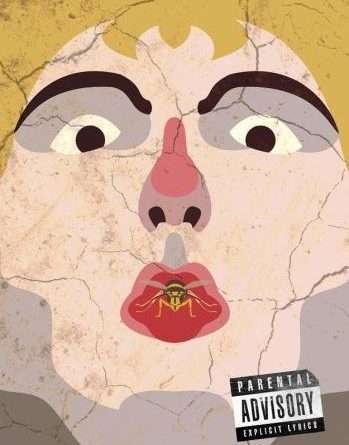

Bad Kid Catullus edited by Jon Stone and Kirsten Irving

-Reviewed by Fiona Moore-

If you read this book on public transport, you may miss your stop. If you let your friends (or in my case their grown-up children) get their hands on it, you may never see it again. It’s absorbing, visually interesting and massive fun.

Some of poetry’s power comes from mystery, all the more so when the writer, time and place can be reimagined again and again: Catullus, lived approx 84-54 BC, a famous Roman poet of love and hate. Do you have to be a fan of his or ancient Rome to like Bad Kid Catullus? No, absolutely not. I admit that comes from a Catullus fan – but if you enjoy the contemporary practice of playing around with poem texts, from genre makeovers, OULIPO, cartoons and collage to multiple translations and high Roman lowlife, then you may like it very well. Also if you have a taste, vicarious or not, for “vice and voluptuousness” (the editors), and for things done with zest and invention. And there’s perhaps something a bit Frank O’Hara Lunch Poems about Catullus – a hopelessly anachronistic thought.

The book contains a selection of Catullus’ short lyrics in Latin: mostly his love/sex poems, which run through the gamut of emotions: romantic love, passionate sex, obsession, jealousy, disillusionment and obscene invective. After each poem there’s one or more (mostly) English versions and responses. Sometimes, the first of these versions is an 18th or 19th century translation, or a mash-up of two or three. This works both as a commentary on how perceptions and language change, and a starting-point for the contemporary versions. I think of Catullus as a victim of Victorian and 20th century bowdlerisation, especially because of the poems’ popularity as school texts, so it’s interesting to find explicit 19th century translations of some of the gay sex poems.

Part of the entertainment is seeing how different poets tackle the same poem. Catullus’ poem VIII (“Dammit, Catullus, forget the stupid girl” in the editors’ 6-word summary) is transformed into 19th century slang by Rowyda Amin and a ‘Secutor v Retiarius (Gladiator Version)’ by Kirsten Irving. The last three lines have Catullus asking whom his girlfriend Lesbia will now love, kiss etc, and telling himself to hang tough. Respectively:

Whom now shalt join giblets? Whose lawful blanket be called?

To whom shalt smacks give? Whose gan nip?

But thou (Catullus!) shut your bone box and die game. (RA)There will be no crowds. No title to snatch.

No iron-head partner, no muscle to slit.

I will hold up my shield against your echo. (KI)

Lovely last line, that.

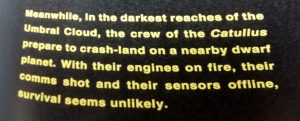

Catullus LI was already a version of a famous poem by Sappho, printed here in the original Greek. He envies the man who can sit next to his beloved Lesbia, hear her laughter etc – when he (Catullus) sees her, his sight’s blurred, a fire runs beneath his skin, his ears ring… We get six modern pulp genre versions, from Teen Vampire to Western. Jon Stone’s ‘Space Opera Episode LI’ has a neat metaphor for the love-symptoms:

Anyone whose teenage years included a Latin teacher not wanting to talk about poem XVI can find various translations of “Pedicabo ego vos et irrumabo”. Sexual invective is Catullus’ way of getting back at critics. Richard O’Brien provides ‘Position 16: The New Criticism’ from the Carmina Sutra, a set of concrete poems in more or less Karma Sutran shapes. This one is a mash-up of critics agonising over how to translate Catullus’ more scurrilous poems.

There are writing exercises, one for each poem. For example, “Future archaeology. Transcribe some toilet block graffiti. Take it home and translate it into Latin. Now re-graffiti it somewhere else. Bonus points if the subject is romance.” This nice idea is also a sort of comment on Catullus’ short poems: romance and obscenities, separate or combined. There are some graffiti-worthy phrases in a set of univocalic poems by Harry Giles; for XXI, in which Catullus warns the lustful Aurelius off trying to seduce a boyfriend, Giles chooses O, for the wide vocabulary it offers from blowjob to coxcomb to dong.

Catullus is a poet of many moods, one of which is deeply heartfelt. (To what extent do you think this is genuine, and does it matter? (discuss).) Heartfelt is the mood least caught in this book, whose tone tends more to invective, humour, sex and vice. Which is fine; those aspects of Catullus have not been done justice in the past.

One exception is the only version of CI, Catullus’ poem mourning his brother’s early death. From the formality of the original elegiac couplets Jei Degenhardt makes a poem of fragmented grief:

Many bodies. Many flat oceans. I’ve been moving

, arriving’s misery. Brother. Funeral.

Last things for you, dead

and silence speaking with ashes

since we’re taken from me.

I guess copyright was a barrier to including any contemporary scholarly translations, e.g. from Peter Green’s The Poems of Catullus. It’s churlish to question that when the editors must have spent ages on the book, working to get everything right. It’s beautifully set out and produced.

This review could go on because there’s so much to talk about. I’ll end with what’s maybe Catullus’ most famous work, LXXXV, a single elegiac couplet.

Odi et amo. quare id faciam, fortasse requiris.

nescio, sed fieri sentio et excrucior.I hate and love. Why I do so, perhaps you ask. I know

not, but I feel it, and I am in torment.

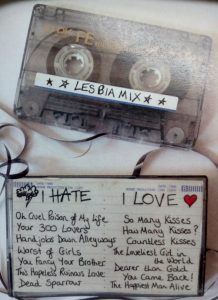

That was Francis Warre Cornish in 1904. Here’s Abigail Parry’s mixtape:

That’s not a bad summary of the Catullus /Lesbia love story. We could all do our own mix-tape of Catullus and this book is a good starting point. In his dedicatory poem Catullus hopes his “little book” will outlast a generation. Well done Sidekick for helping propel it through its 22nd century. Bad Kid Catullus would make a great present: for poetry lovers, lovers of Latin, other literary types and lovers generally.