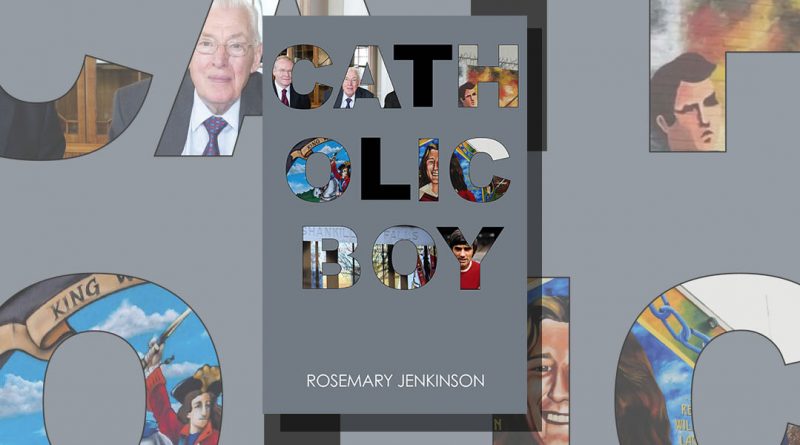

Catholic Boy by Rosemary Jenkinson

-Reviewed by Jenny Booth-

Catholic Boy (Doire Press) is Rosemary Jenkinson’s third collection of short fiction, shortlisted for the 2019 Irish Selection for the EU Prize for Literature, as well as making the Edge Hill Short Story Prize longlist. The stories in Catholic Boy are largely set in Belfast, where Jenkinson spent some of her childhood and, after a period away at university and teaching English abroad, returned to as an adult. Belfast is not just a place that Jenkinson experienced as a background to growing up, but one that as an adult she has gone to considerable lengths to live and understand. In an interview with The Gloss magazine, Jenkinson recalls spending time with Loyalist communities looking for writing material where she was, “issued with threats of being put in a wheelie bin and burnt, being dragged down a hill by my neck – all experiences submitted to in the name of research.”

This breadth of experience is reflected in the writing. Belfast appears as an atmospheric presence. There are the landmarks of the Troubles, the Falls and Shankill roads, the Divis Flats, the peace walls. Jenkinson’s own roots in Protestant East Belfast reflectively and poetically appear. Alex ‘Hurricane’ Higgins, who the narrator meets in a chance encounter, twirls his cue ‘like a band-pole on the glorious Twelfth.’ Working class Protestant men are described as ‘the new model army of the East, where they were all churned out, identically hard as if hammered straight out of the long-defunct shipyards. ‘ Jenkinson intersperses politics and history with the natural setting. A Belfast tour guide’s internal narration reads:

“Then onto the safety of the Shankill with its oul familiar stories and today the riotous autumn leaves raced along with the bus as it crossed the border and a sudden shaft of light spilled out of the clouds and the heath on the mountain top shone gold.”

Many of the characters in the stories display frustration with, or are at odds with sectarian identities. Ruth who seduces Jarlath, the eponymous ‘Catholic Boy‘ reflects, “He came from the other side of the peace line and it didn’t faze either of them.” In ‘One City, Two Tours,’ Glen works for a Protestant tour guide and has a cousin in the UVF, yet has ‘long ‘Catholic’ hair and hippy clothes.’ He secretly flirts with Finn, a woman from the rival Catholic tour who tips him off about such opportunities as playing a hunger striking republican in a film shoot. In ‘Giannino,’ Vivian, from a Catholic background, receives death threats when he publishes articles in a local newspaper critiquing Irish Republicanism. The stories suggest other things are or will become more important than sectarianism; love; a wider world. In ‘Giannino,’ Vivian’s Milanese flatmate Gianni is tone deaf to the hierarchies and conventions of Belfast. Vivian initially fears Gianni’s innocence as dangerous, but comes to see him as unburdened by provincial concerns and hatreds; he concludes, “the real way into a new world was not through religion or beliefs or ideas but through people.”

Another feature of the collection are female protagonists who are unapologetically independent and sexual. The woman in ‘Revival,’ describes Alex Higgins as ‘preeningly sexual, loose-limbed in the pleasure of predation.’ The implication of the story is that they are at least similar enough for the narrator to understand and admire something in him. In a later story, ‘Love History‘, the female protagonist says ‘I liked hunters. I understood them because I was one myself.’ ‘The Ideal Man‘ opens with Jess making a new years resolution to get married by the year’s end. She dutifully sets her designs on Stephen, ‘a graphic designer and twenty-seven which was perhaps a bit young, but that was okay because he was balding and looked older.’ Reader, she doesn’t marry him. I also enjoyed reading stories about characters drifting and exploring, not in a Patrick Leigh Fermor Grand Tour way, but teaching English in language schools across the continent and signing on.

If we didn’t face imminent annihilation from climate change, these stories could be a valuable record of a time when it was possible to spend days writing, fucking and signing on, which even today seems almost too fantastical to believe.

Writing about sex is a necessarily personal and therefore highly subjective thing. However, ‘he was on top of me and it suited me that way because I could hold on to his rocks of buttocks while he dug and stabbed inside’ didn’t especially set my mind on fire. A deeper issue might be that the female protagonists in the collection are, mostly without exception, hard drinking sexual hunters. This might lead them to different ways of seeing the same thing, the focus on explicit eroticism in ‘Love History’ for example, contrasts with the tenderness in ‘Song For a Polish Stranger,’ but as the collection progresses there’s a sense of predictability.

The same could apply to the other common trait in the collection that could be designated ‘outsider frustrated by rigid sectarian identity.’ In the final story, ‘The Lough,’ Damian, a former member of the IRA feels sadness and horror when recalling his involvement in the abduction and murder of a mother of three children. This must be writing at the margins of Jenkinson’s experience, yet she imagines Damian’s situation with great empathy and sadness as well as offering the ultimate justification for the collection’s weariness with sectarianism. However, Damian has long rejected violent Republicanism by the time the story takes place. While minor characters in the collection are partisan, there’s little to explain what might motivate someone to adhere to sectarian identities rather than dismiss them.

I couldn’t speak to whether an overabundance of partisan voices of either side already exists in literature. I feel more confident that sexually independent liberated women aren’t massively overrepresented.

However, I did observe a certain uniformity of outlook within the collection’s protagonists. Whether this is valid or important as a criticism is down to the tastes of the author and other readers.

Catholic Boy is an irreverent, lively, funny and thoughtful collection of stories. Jenkinson makes use of her deep knowledge of Belfast, as well as her experiences outside of it, to deliver a perspective of the city and Northern Irish identity in the 21st century that is detailed, tangible and complex.

*

—

- View the twelve titles on the Edge Hill Short Story Prize 2019 Longlist (announced 30 May 2019)

Sabotage Reviews will be taking a look at a number of the indie-published titles on the longlist, including Leila Aboulela’s Elsewhere, Home (Telegram/SAQI), Michael Conley’s Flare and Falter (Splice), Wendy Erskine’s Sweet Home (Stinging Fly), Clare Fisher’s How the Light Gets In (Influx Press), and Vicky Grut’s Live Show, Drink Included (Holland Park Press).

- View the six titles on the Edge Hill Short Story Prize 2019 Shortlist (announced 9 August 2019)

The winner of the Edge Hill Short Story Prize for best single author collection will be announced on 25 October 2019.

—