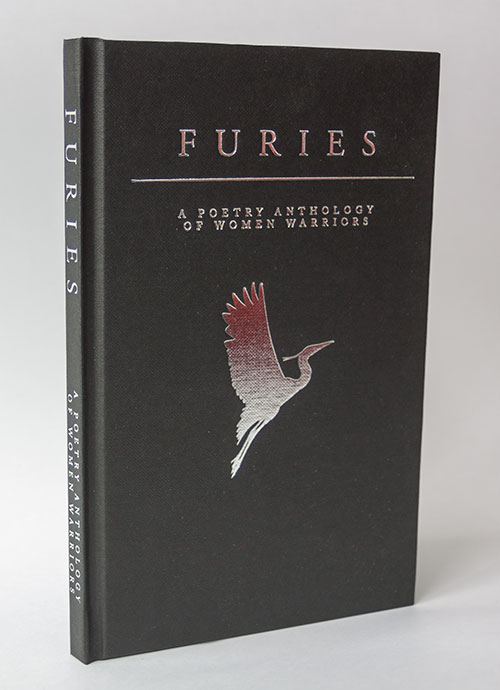

Clinic III (ed. Rachael Allen, Sam Buchan-Watts, Andrew Parkes, and Sean Roy Parker)

-Reviewed by Faye Lipson–

Born out of the London-based multidisciplinary arts platform from which it derives its name, Clinic III bears a certain weight of expectation. Its predecessor anthologies have both been warmly received, with a previous Sabotage review praising Clinic II for containing ‘poetry ripe for the stage as much as it is for the coffee table’. This new anthology does not fall short.

Clinic III is as zippy, slick and well-oiled as a vespa, and it prowls smartly across a modern poetry landscape, revving and purring by turns.

The book’s dramatic changes of pace begin with its extraordinary cover, for the poetry therein is sandwiched between a disorientating abstract collage on the front cover, and a gory comic about a cartoon hammer on the back. I often take high production values in a book to be a signpost for similarly high editorial values. In the case of Clinic III, my belief is corroborated.

There is a pleasing absence of the more stultifying prosy work we sometimes see elsewhere, as this vehicle carries little extra baggage. Much of the work is light and crisp, with a flair for musicality and deft use of internal rhyme. Perhaps because of the interdisciplinary nature of Clinic, which seeks collaboration between music and poetry, many of the 35 poets possess a well-developed poetic ear. These poems read beautifully.

Eileen Pun (fabulous name) was a judicious choice of opening poet for this book. Her ‘Studio Apartment: Sunday’ is witty and well-observed, appropriating the honeyed tones of a Foxtons advertorial to explore the ‘bijou palace’ of the pokey London studio to which so many are consigned. Artfully blending urbane humour and ennui, Pun sets the tone for the rest of the anthology.

Another standout poet is Henry King, whose three poems whisper in dialogue with each other across the pages. ‘For Ava’, with its beautiful lyric qualities, draws out the biblical qualities of the Ava (derivative of Eve), positing the name’s newborn recipient as an Edenic emblem of hope and newness. Just across the page, ‘The Third Adam’ speaks of a fall from grace into urban desolation.

The excellent Helen Mort provides a note of melancholy with a beautifully understated poem about mournful-eyed whippets. It is also good to see Clinic editors Rachael Allen, Sam Buchan-Watts and Sean Roy Parker investing in the success of the book by each doing their own skilful poetic turns.

All this is to say nothing of the startling and absorbing artwork with which the poems are interspersed. It is my complete inadequacy as an art critic, rather than any deficiency in the art itself, which prevents me commenting further on this aspect of the book.

If I have one small criticism of this book, it would be that a tiny portion of the poetry it features is almost completely impenetrable, even with repeated readings. Megan Levad’s work, particularly ‘Young Digerati’, perhaps best encapsulates this difficulty. The use of disconnected phrases and mysterious left and right alignment seem to allude to work created by arcane rules.

The poem pelts you with discombobulating phrases from opposite sides of the page: ‘told our families “Once a year/ up next: The Way We Live Now/ double vanity!’ I am sure there is method in the madness, but it’s not discernible to me.

Let there be no mistake about this: I am very much for poetry which rewards the patience of the reader by a slow and gracious peeling back of its folds of imagery. Indeed, I believe the best poetry can continue to spark new readings, understandings and lateral connections in the mind of the reader many years after she has first encountered it.

However it feels like Levad’s work was constructed using particular rules or writing exercises which I was not privy to. There is much to commend about experimenting in this way. Nonetheless, when publishing such poems in an anthology, the reader mustn’t be forgotten. A general framework of literary appreciation is not always adequate for understanding works produced by more obscure sets of rules or exercises. I think that in a number of cases, a line or two of preamble about the creation of the poem would have enhanced my experience as a reader. Having said this, the vast majority of the book would be very accessible to a patient and committed reader, and a joy to have on one’s bookshelf.

Overall, Clinic III is as appetising to the poetry fan as fresh brains are to a killer zombie – a fact not missed by Clinic poet Jonny Reid, whose ‘Twenty Zombies’ sums up my feelings toward the book exactly: ‘I am zombie 20, and oh my god you look delicious’.

Pingback: clinic » clinic iii