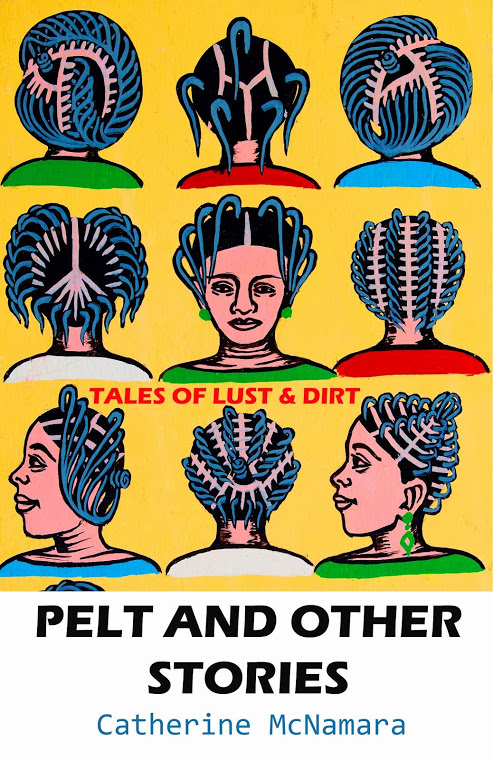

Pelt and Other Stories by Catherine McNamara

-Reviewed by Eleanor Hemsley-

Looking at the cover of Pelt and Other Stories I half-expected to read about women kicking men’s arses and winning in every confrontation. I expected to be reading about empowerment and equality across the globe, but instead I got something much better. I opened the book and found myself lost within an in-depth exploration of humankind that didn’t sweeten the reality of the world, but instead showed the true nature of humans. And this is where I will begin.

I find that with most books I read I become so lost in the fantasy characters, wishing that I was them, that I don’t realise just how fake they are. In these short stories though I found myself sympathising so much more, because I could see all of these things happening. I could believe that a mother who had never been exposed to science would turn her back on medicine, even if it hurt her daughter, that a woman who has been raped would deny it and pretend it never happened, that a man could be so proud that he’d rather risk his life than be ashamed.

It’s the cruel nature of the characters that drew me to reread the book a second time. The first time I read it I found myself shocked that some of the things happened, but the second time I could see that it all could happen, and probably has. So I found that McNamara had cleverly and subtly made me wonder why all this was such a shock to me to begin with. This isn’t a fantasy, it’s realistic, like reading a newspaper (except with much better wording). McNamara made me realise just how cruel humans could be, and at the same time made me accept that it’s a reality that most of us deny.

In these short stories McNamara has managed to capture the essence of so many different relationships, and has portrayed them well. She shows a woman, silently disagreeing with her husband, then another outwardly disobeying hers. Of course there’s the typical clingy-mother-independent-daughter relationship too, only told in a way that’s different to what I expected.

It was lovely to find how different each story in this book was. I found it disappointing to see that some stories were overly predictable, that from the start I could guess what was going to happen, but then in other stories I found I was led to believe one thing only to see everything turned around at the end. Take the first story, ‘Pelt’, for example. All the way through I could see the struggle between black and white veering towards white, with Rolfe seemingly favouring his estranged wife, and even the girls who work for him, putting the white woman above the black, so naturally I felt empowered at the end when the beautifully outspoken black woman comes out on top. But at the same time I felt cheated that I had been led to believe one thing and ended up with another.

I found this happening in many stories, yet the feeling of being cheated never stopped me from reading, probably because I found I instead got the better ending; the one I wanted or feared. And then I found that when it came to the stories that didn’t surprise me I was more disappointed because I wanted the exciting and unexpected ending. Either way, I found each story just as compelling as the last until I found that the last page had turned and there was nothing else to stay awake for.

The author’s voice shows prominently in these stories. At first I found it unique and exciting. I loved the bluntness of the character in the first story, the way she described her lover’s wife as having ‘thin downy lips and a wide jaw. Little breasts. Flat arse.’ This made me laugh and I could hear my friend saying the exact same thing. I love how real it is, how McNamara isn’t polite, but instead gets right down to what she wants to say. I found the character raw and this made her even more endearing.

That is, until I kept reading. I got to the second story, then the third, and all the way through the book just waiting for another voice to pipe up and take the stage, but no luck. Don’t get me wrong, I love the originality and the brutality of this narrator, but every narrator in the story has the exact same voice, with the same tendency to be harshly truthful. And this disappointed me. I found it hard to distinguish between the stories and narrators, found myself getting confused about who was who and where they were, and even in one instance couldn’t figure out the gender of the narrator until the end of the story.

But then it occurred to me that perhaps this was purposely done. I look at the book now and see that it is a realistic yet fictional observation of the way humans are with each other and themselves, and it makes me wonder whether the same voice was used over again to add to this meaning. It could be McNamara’s way of saying that deep down all humans are the same, that all of us are just as blunt and bitchy and cruel as each other. I know, it’s a horrible lesson to get out of a book, but it’s what we read for. We read to experience things we would never experience elsewhere, to feel things we’ve never felt before and never will, and to think new thoughts. So whether the voice doesn’t change to show the monotony of people’s thoughts or just because the author found it hard to get out of it we’ll never know, but it made me see just how similar we all are.