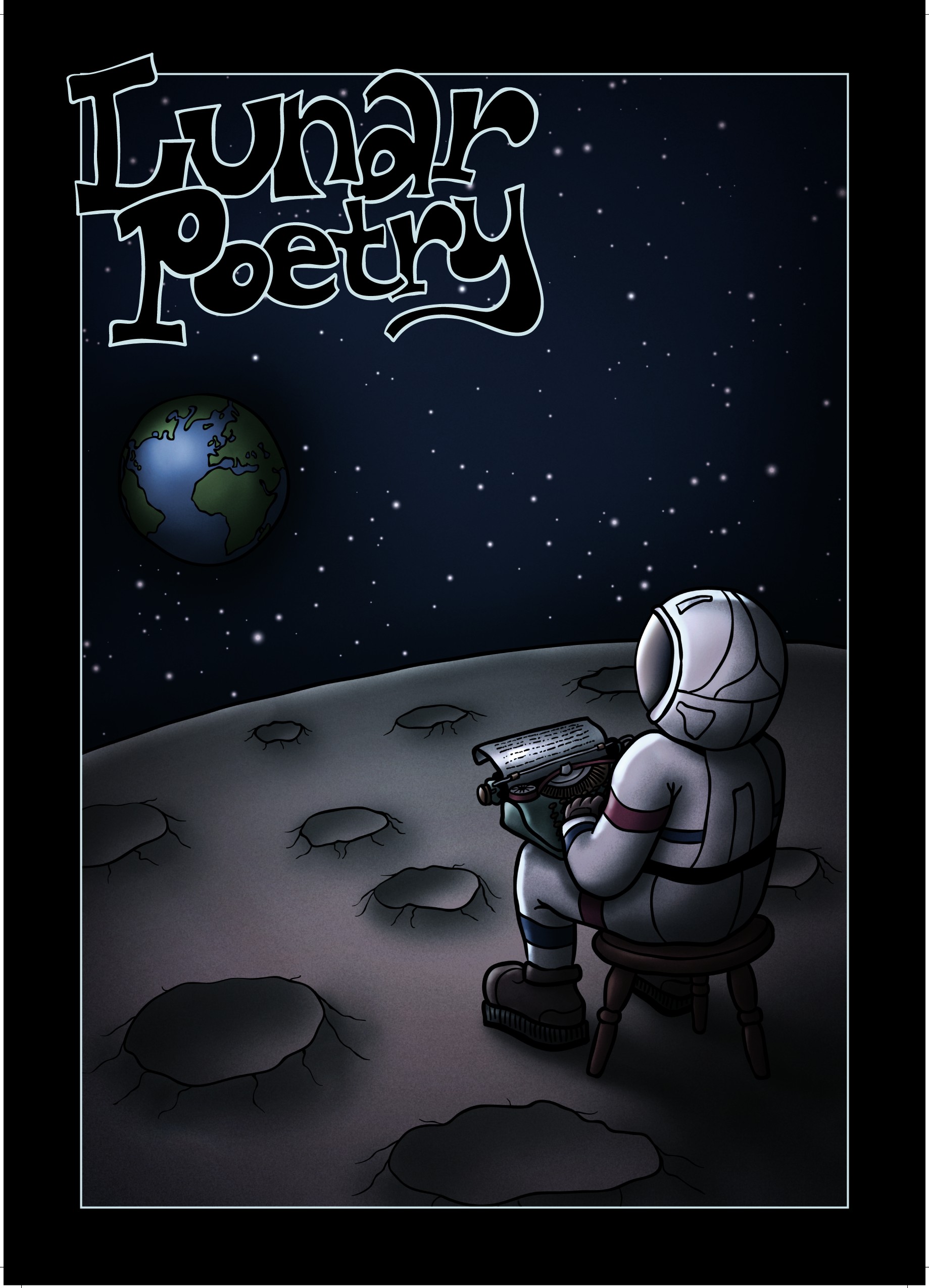

Lunar Poetry #1

-Reviewed by Zara Raab–

Lunar Poetry earns its name in this first issue, full of tunes and nonsense, word play and wit (right down to the names of the poets), weddings gone awry and stanzas sent topsy-turvy. Lesley Burt’s “Turning the Picnic Tables” recreates in four tercets Manet’s famous painting (Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe) with gender roles reversed: male nude ogled by a gaggle of fully dressed women picnicking on the grass. Kirsten Irving’s ” Lunar Poem 1,” which open this issue, recounts the story of a bride who disappears the morning after her wedding, “the upstart day so raucous in its light”:

She must have gone down for omelettes,

gone out for a smoke, or a walk or perhaps

to call on her lawyer. Perhaps by lunch

you’ll be some way sober, signing a disclaimer [. . . ]

Also in this vein is D.S. West in a spectacular end-of-romantic-love-poetry poem, “Let Her Be the Last.” It begins with the usual how-do-I-love-you’s, but quickly figures a stanza that’s gotten out of hand as a living person, who must be drugged and taken to the E.R. The stanza-as-man wakes and runs “his hand across the stitches: ‘What have you done to me?’ he asks.

The shortest Judas put his palms up,

as though pitching a movie.

It’s the greatest thing. Don’t

be mad, but–your doctor told us

there was a better poem

hiding in your intestinal lining,

and –”

I’m going to die soon, aren’t I?”

“Pretty spectacularly, yeah. Want

some E?”

It seems appropriate then that at the heart of this spunky issue is a long piece, the first of a two-part essay on Spoken Word poetry, by Paul McMenemy, the editor of the magazine. Although it is often thought that print magazine (“page”) poets and spoken word (“stage”) poets traditionally ignore each other, McMenemy introduces a historical refutation with Tim Wells’ “ranting poets” project, an archive cataloguing relevant articles, reviews, and interviews of that movement’s decade that demonstrate the superficiality of this imposed divide.

The poems in this issue are anything but shut up in a book, though the 80-page magazine is bound. Some poems, like Bob Beagrie’s “Wolfling”, can be found set to music on the magazine’s audio page [www.lunarpoetry.co.uk]. Performance, too, seeps into such poems as Hugh McMillan’s clever riffs in dialect on Greek gods interfering as usual with humans, “couldnae help it a Goddess telt me to” (“Bacchus and Ariadne”). Dialect and colloquialisms, another link to performance, feature in “Zeroes,” by Gary from Leeds:

It’s still nil-nil lads

It’s never not nil-nil hereCaptain call to arms

Though they’ve just smashed

Their fifth in

Against a rag-tag squadron

of misfiring misfits

Who’ve never acquainted

Barn door and banjo

in Anger or any other stateIt’s still nil-nil lads

Goal number six

Has just dribbled home

Goalie lips quiver noticeably

Defenders look away

This issue includes interesting versions by Martyn Crucefix of the I Ching, the ancient Chinese text that gives advice on wise government:

In this world, where what is laid straight

engenders so much running crookedly

Crucefix’s text warns, “You want to govern? Serve the good? / Look to reserve as much as you give.” Governing a nation is compared to frying “a delicate fish” and “real power is female, rises from beneath.” All of us can probably take the meaning of:

Whatever is problematic must be

dealt with while it is still manageable–

anything serious while it’s incipient…

Elsewhere, there’s blathering by Godefroy Dronsart in “The Miser’s Dream” and “Streetwise Manners”, but more serious, even somber poems, as well, such as Myra Schneider’s evocation of the early winter doldrums in “Windows”: “All day the grey, low-bellied sky weighs me down. I pine / for a hint of tangerine, of rowanberry but hopelessness, / like the damp, is quick to nose its way into everything.” Magdalena Wolak sings of one under the delusion that he no longer exists (“song of Cotard”). Fanni Suto’s haiku (“Summer wires”) subtly evokes the rusty browns of autumn. Strong, too, is work by David Grubb, as in these lines from “Approaching Prayer”:

it is the time of dead

nettles and wind gusting its cold ghosts.

What do the stones have to say,

can you hear the old speaking sticks?

What remains is earth tokens, owl ideas,

the light behind the eye.

What does an old wind have to say

as it lies down with lies, these cracks

between prayers and white grass?

In Grubb’s “The Names of Parrots” the owner and caretaker of a bevy of parrots dies, so the parrots await their evening cake in vain. And when they are taken to a hill top for the casting of their owner’s ashes to the wind, they wait “as the white dust was caught by a wind and rose and rose towards / the top of the sky, beyond bird song. . .”

Another strength of Lunar Poetry are its reviews. A regular feature, called “A Poem in Detail,” sees critics take one poem from the issue for a roundtable discussion. This month Wynn Wheldon, David Clarke, and Claire Trévien debate questions of truth–“the way in which poetry inhabits this world between fiction and reality”– in Carolyn Oulton’s poem “Second prize answer” featuring Hester C. Cholmondeley at age 12 1/2–one of five poems by Oulton in this issue..

But “A Poem in Detail” is just a taste of what comes toward the end of the issue: Half a dozen or more full reviews of recent poetry collections, each sensitive and well-crafted, no mere précis, but a thoughtful accounting. For me the most insightful and interesting reviews were those by David Clarke. These included three new books from the Irish press Doghouse (and final books, as Doghouse will cease publishing with these collections): Gene Berry’s Unfinished Business, Mary O’Gorman’s Flames of Light, and Catherine Ann Cullen’s Strange Familiar.