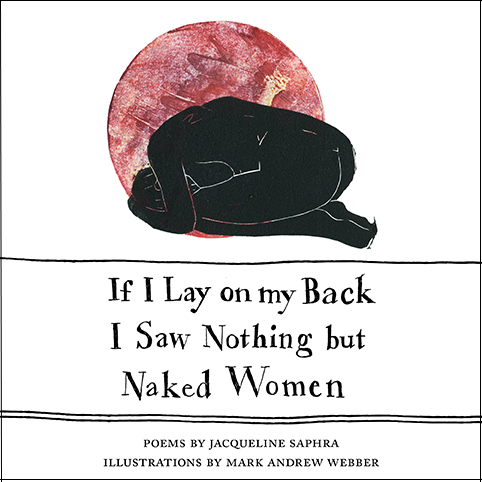

If I lay on my back I Saw Nothing but Naked Women by Jacqueline Saphra (ill. by Mark Andrew Webber)

-Reviewed by Alice Allen-

Jaccqueline Saphra’s sequence of prose poems opens with the startling statement:

When I was a child I tied my mother

and father together with bandages and

put a song in their mouths.

What follows is an extraordinary memoir of childhood: haunting and comic, disturbing and bizarre. It is a child’s view of the world but narrated by an adult, and so the story is told with a double perspective, the fresh naïve vision of a child laminated with an adult’s wry humour.

The child’s parents and their subsequent partners march through the poems trailing a variety of character traits, variously flamboyant and bohemian, intense and absent-minded, neurotic and utterly lost as they pursue their respective professions and interests at the expense of those around them. On one level the child inhabits an exciting world. The adults are often figures of fun and absurdity, hiding in cupboards to study law books, opening the door to the postman naked, making hopeless pottery jugs that won’t pour properly. This is the material of quirky family anecdote but the sequence is underpinned by a darker tone. Like the mothers, fathers and step-parents in fairy tales, the adults appear self-serving and fallible, disconnected from each other and, more importantly, from the child. There is sadness at the heart of these poems. In a world which seems to provide little emotional nourishment, comfort and stability is sought by attempting to control and order words, her own words and those of the people around her.

But this attempt to control words is an impossible task. Like the inanimate objects in a Svankmajer stop-motion film, words in Saphra’s poems exist as objects which can come alive and have a will of their own. Hiding problematic words in the compartments of a desk, the words multiply and converse:

Sometimes they whisper

in the dark. At quiet moments, if I put

my ear to the ink blotter, I hear the

longer ones mount the shorter ones.

Weeks or months later, I catch little

phrases or cries coming from inside.

More disturbing still, words from stories told by her mother ‘re-formed themselves and sidled back into her open mouth’ while she slept.

Elsewhere, words are used in the power struggle between the child and her step-mothers. The second step-mother liked some of the child’s words so much ‘she often kept the best ones for herself’, once ‘pulling a whole string of them out of her sleeve at a dinner party’. The third step-mother ‘bagged up all my old words, took them to the charity shop in her rusty Honda and redesigned my father’s house around him’. The child’s words are appropriated or taken away in an assault on her identity and her position in the family.

In the final poem of the sequence the mother and father are living on different continents and words spoken via long distance telephone calls become increasingly unsatisfactory and frustrating:

You could

never be sure what you heard. Certain

phrases were often bent or broken in

transit, complete sentences drifted away

and were lost in the exchange.

And so the written word finally seems to provide a means of attaining control and permanence in an elusive and beguiling world:

Airmailed scrawls in permanent

ink proved more dependable. Tightly

trussed with rubber bands, unable to

escape, the words waited immutably in

the dark.

Like the bandages she fastens her parents together with in the opening poem, the rubber bands are used to hold the parents’ words together and to keep the text still. But it is an ironic victory; the words remain obscure and unattainable, hidden in the dark.

Despite this darkness, the poems in this book are alive with the child’s close-up vision of the world. Her step-father, the artist ‘had a palette made of hardboard and his ancient brushes shed bristles onto the paintwork’. This is a world of light and strong colour and Mark Andrew Webber’s linocut studies in the nude human form perfectly complement the tone of the text. The dark form of the nudes are set alongside blocks of jewel-like colours – yellows, pinks and blues, sometimes fragmented, sometimes whole. In an interview with the Poetry School, Saphra described the project as a picture book for adults and, as in all successful picture books, the text and the illustrations work together to create a unified emotional effect. As you would expect from an Emma Press publication, this book is an object to cherish, to handle carefully and read over again.