Refracted Light: 20 Poets Respond to Jackson Mac Low’s Light Poems ed. by James Wilkes

– Reviewed by Ryan Ormonde –

Refracted Light is a mini-anthology providing a multi-site response by 20 poets to Light Poems by Jackson Mac Low, ‘a layered process of creativity that extended over more than two decades’. A couple of responses, in line with Mac Low’s ‘diastic’ grid-tool for generating poems, develop a transparent or pseudo-transparent process of encoding and decoding. These are Mac Low’s 1st Light Poem Transcribed to Morse: Script-Score for a Three Person Performance by Chris McCabe, and Star Fain I (Table of Bioluminescence) for Jackson Mac Low / Star Fain II for Jackson Mac Low by Redell Olsen.

There is a certain delight (de-light?) in working out McCabe’s three-stage process here. Mac Low’s first Light Poem is scanned for a pattern that can be translated into Morse code, which in turn generates letters that refer back to Mac Low’s chart. Loaded with potential energy, this text is underscored by a titular wish that it be performed by three people. Mac Low’s chart is a generator: it invites anyone to perform its Tarot-like procedures (or not). Redell Olsen chooses to construct a new chart, shifting Mac Low’s system towards a more contemporary threading of texts, in a work that surpasses the late poet’s artistry while honouring his ingenuity. This new chart stands alone as a work ‘after Mac Low’.

Stephen Emmerson encourages us to experience words as pharmaceuticals: are the identical sugar pills in a bottle labelled ‘LIGHT’ comparable to Mac Low’s light names? In Light, Emmerson’s captioned photograph makes reference to a presentation at the anthology launch. Is selecting and taking a pill the procedure we perform here? What is the outcome? Holly Pester has an equally distinctive practice, in this case a regenerating performance-study of phonetics in sympathy with innuendo. In Lamps are a Turn on, she tugs out anthropomorphic lights from Mac Low’s chart and lets them play together.

Two poets concern themselves with light as experienced by Inuit communities. In Light Poem #1 the spelling of Inua Ellams’ first name (‘my native / self’) seems to spark an inquiry, Arctic perception contrasted with an image fusing light bulb with star: ‘these egg-sized supernovas’. In Tartuq, Sophie Mayer uses Inuktitut words to help illuminate the ecological-political consequences of the harnessing of light by mankind:

big, hell (fire) – iqqumaaluq

(puts out) – qamittuq

dark (without light) – tartuq

A documentary film by the Arnait Collective, Before Tomorrow, is cited in the poem, and it is clear that Mayer is responding as much to this as to Mac Low’s series.

In Undaughtered by Sarah Crewe, the word ‘daughter’ darts through two sections of a verbal field until it meets ‘son/sun’ in the third, culminating in ‘you are son’, followed by an isolated final line: ‘you are light’. Undaughtered is an (un)naming poem, a dedication to a maybe-being, a ‘hypothetical’ her/him. Crewe lifts two names from Mac Low, ‘rose light’ and ‘ruby light’, and lets them halo: ‘rubellite’, ‘ruby christabel’, ‘iris rosa’, ‘rosita’, finding new light names.

Mendoza’s eulogy LIGHT POEM FOR THE TRANSMIGRATION OF SOULS: IN MEMORIAM JAMES HARVEY begins by listing the effects of ‘electric current passed through’ four noble gases, uncovering ‘erroneous Light’ in the midst of its philosophical and sensitive articulations. Dorothy Lehane performs a struggle of ‘i’ against ‘you’ around the roles ‘physicist’ and ‘lecturer’ in becoming physicist: for Jeff Hilson; tempting us to read ‘now i am telling / but the showing has overlapping fugues’ as literary self-reference. Involucrum sees Edmund Hardy caught in a metaphysical oscillation in encountering Mac Low’s ‘grid of light names’. In Unselfish Light Poem SJ Fowler diverts the part-Chinese language of an instruction manual: bullet points, dividing lines and floating electrical symbols offer deceptive reassurance. Uncanny signals await.

Emma Bennett and Patrick Coyle are entranced by Mac Low’s imaginative/suggestive/generative process in filling the cells of his spreadsheet: Bennett’s list seems drawn from memory in Light Poem: for myself in the 90s, whereas Coyle’s 280 words for different kinds of light seems grounded in the present – somewhere between itinerary and itinerant – and alphabetised for good measure. Philip Terry and Tim Atkins are explicit in their evocations of Mac Low: Terry’s focus, in 55th Light Poem: Unwritten, is an unexplained gap in the oeuvre, while Atkins announces a more personal absence in Lost Floppy Disc Sonnet in Memory of a Missing Correspondence with Jackson Mac Low, 1998-2001– what might Tim have asked Jackson? This poem is printed alongside a scan of a child’s drawing adjacent to a jaggedly typewritten line of anthropological substance.

One poem is so carefully arranged that it seems to incorporate its page number, the glimpses of the staples binding the anthology, the long line dividing its title: Light Poem by Nat Raha. Emerging from space is ‘de[light[lete’, followed by a line break creating a step down into ‘/ful phenomena’. Colin Herd’s Light Play: maybe for Iain Morrison and I to perform sometime next solar eclipse is a fanciful score, the pre-emptive document of a singing, cantering al fresco performance. In Light Poem (asterism) after Mac Low and Light Poem (grid) after Mac Low, Amy Cutler speaks directly of ‘something lacking’ as thoughts dance over ideas of light, ‘grid’ and the typographical device ‘asterism’, which is written into the verse to stand for light and lack.

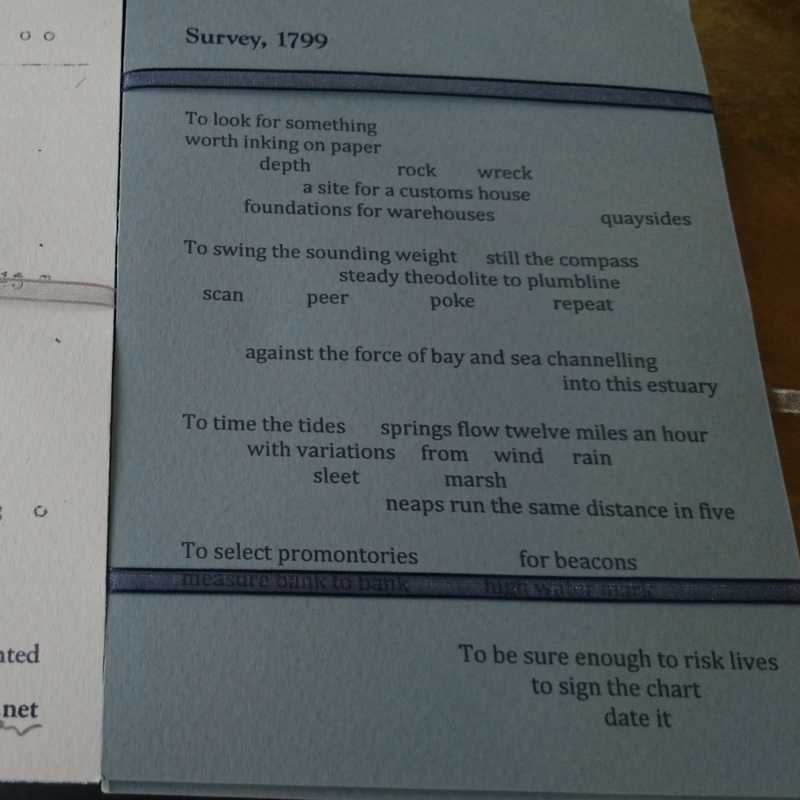

Tamarin Norwood studies slippages in Mac Low’s handwriting in EYE LIGHT (s’io credesse), comparing their appearances in the original chart to the faltering movements of bees in a hive. Finally, the editor of the anthology, James Wilkes provides a densely textured double response – to composer des Prez as well as poet Mac Low – in Nymphes des bois (i.m. Josquin des Prez). Wilkes deserves praise, too, for assembling this spectrum of poetic responses to a luminous experimenter.