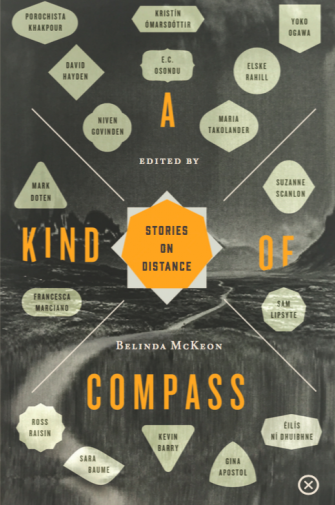

A Kind of Compass: Stories on Distance ed. Belinda McKeon

-Reviewed by Rebecca Burns–

The first thing to say is that A Kind of Compass: Stories on Distance is a beautifully produced book. Larger than most paperbacks, with a soft, pliable feel, this anthology of short stories feels flexible and portable; just the kind of book, say, to stuff in a back pack or curl around on a train several hours into its journey. Indeed, travel features prominently in this text, interested as it is in taking paths that ‘veer[s] off course’. The book is edited by Belinda McKeon, is around 250 pages long, and comprises seventeen short stories by a selection of authors. The theme, obviously, is distance, and in all guises. In McKeon’s lyrical preface, she states that ‘a good story takes its readers to places to which they didn’t particularly want to go’, and the characters in the pages that follow are all either led or set out to find what it is they feared, lost, yearned for, or avoided.

Distance, in these stories, takes both physical and emotional forms. In the opening story, ‘Terraforming’ by Elske Rahill, Caitriona secretly attends a seminar for those applying to go on a mission to Mars. Her husband doesn’t know about her ambitions – she tells him she is visiting her sister and worries about the credit card statement. Such mundane actions, typical of someone conducting a clandestine affair, is incongruous with the scope and ambition of her hopes. What particularly stands out in this story is the effect her potential leave-taking will have on her son. Should Caitriona get to Mars, she will never see him again. She accepts this emotional rendering with an ease that is sorrowful to the reader:

[S]he will grow away from him over the ten years it will take to train for Mars, and that is right of course. A curling beat inside her and then a cord. Then a breast and then a head in her neck. Then a hand in hers and then no hand because that’s how it is with time and space.

While Caitriona is preparing to leave her son, other stories in A Kind of Compass explore what it means to return to a relative or a lover after a period of detachment or loss of contact. In ‘The Naturals’ by Sam Lipsyte, Caperton returns home to his dying father after being summoned by his stepmother. The pair share a cordial but not loving relationship, the barriers between them humorously evinced through his stepmother’s pathological refusal to allow Caperton to inspect the contents of her fridge. The search for meaning is important in this story, as it is for the collection as a whole. Caperton is unable to find words of love and healing for his father until almost the end but, throughout the tale, he seeks to find narrative and order to his life. Various characters personify this search – The Beast, a wrestler putting on an illusion for the audience, and a friend of his father who tells stories at the local library. In Yoko Ogawa’s ‘Six Days in Glorious Vienna’, Kotoko also seeks a tentative kind of meaning by visiting a dying lover; it has been decades since she last saw him, but she finds a cautious, weary comfort in spending time at his deathbed:

She would stroke his hair or straighten the collar of his pyjamas or moisten his lips with a piece of damp gauze. But she did all this with the greatest reticence, as though to announce by her manner that she had no right to do so and would instantly retire when some more appropriate person appeared to care for him.

The return to an old lover is also the theme of Francesca Marciano’s ‘Big Island, Small Island’. Andrea had disappeared some fifteen years before. He lives on an isolated island, and is totally changed from the person his ex-girlfriend – Stella – remembers. Paradoxically, he has removed himself physically from most of society, but has become more at ease emotionally: ‘[H]e’s a different person in this new incarnation – that cool aloofness, that lightness of touch he had when I knew him, seems gone’. It is not long, however, before Stella recognises the peace brought by distance: ‘maybe he was relieved when he found a place where he could shrink and settle into a smaller life, away from the eyes of others’.

Kevin Barry contributes a story, ‘Extremadura (Until Night Falls)’; a mystical, strange tale about a man passing through a town conversing with a dog. Barry’s recognisable humour is apparent, and is typically jarring in its delivery: ‘all across the silver hills in the east the cold spring night lovelessly descends. February is an awful fucking month just about everywhere’. Despite the humour, we learn the painful reason behind the man’s wandering and his disconnection from society.

A Kind of Compass explores what it means to lose a loved one, and also the longing to break away and find freedom. A father is lost at sea in ‘Holy Island’; a ghostly husband visits a grieving wife in ‘New Zealand Flax’. A young Nigerian man leaves home and tries to make a new life for himself in London in ‘The Place for Me’. Each story in this collection explores what it means to be distant, and the anthology is thoughtful and cleverly put together, with each tale adding another layer of meaning to the overall theme.