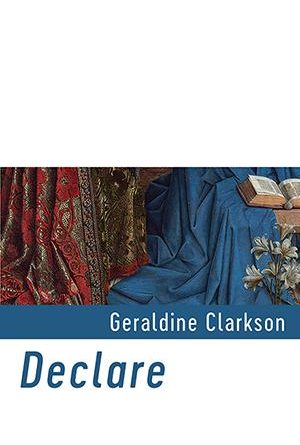

Declare by Geraldine Clarkson

– Reviewed by John Mee –

Declare is one of a trio of publications by Geraldine Clarkson in 2016. Its arrival in June followed the appearance of a dozen of her poems in Primers: Volume One (Nine Arches Press) in April, and preceded the publication of a second pamphlet, Dora Incites the Sea-Scribbler to Lament (smith|doorstop), in October. Clarkson, a Midlands poet with roots in the West of Ireland, has also had an impressive run of success in recent poetry competitions. This creates high expectations for Declare, and it does not disappoint.

These poems are strikingly musical; according to Clarkson’s description of her creative process, “the sound always comes first”. There is, of course, a danger that emphasis on the sonic dimensions of a poem may come at the expense of the sense. However, Clarkson’s work is also marked by intelligence, a command of tone, and an underlying seriousness. In truth, there is sometimes such exhilaration and skill in her music and wordplay that all reservations are disarmed.

A good example of this exuberance is “T-E-N-G-U” (currently available to read at Tears in the Fence). Its subject is a “[m]ythical Japanese flying creature, associated with spirits of priests and nuns, neither damned nor blessed”. The prose poem gives a surreal commentary on the creature, featuring a recurring, energetic riff on its name. For example:

Tengu—in Anglo-Saxon, Tengu. In letters, Renga; in South American dance, merengue, tango. …

In Chinese, Den-gu. In nursery English, Ten-

gooey. In primary-based colours, tangerine. In prime numbers, ten-minus-3-gu; in Kazakhstan currency, tengeh. …

In Australian, Ken-do. In Betweenheavenandhell, Tengu.

“T-E-N-G-U” is one of eight prose poems which are amongst the strongest in the pamphlet. In the menacing fairy-tale of “When we awake”:

the eldest brother—it is so obvious that they are brothers, the Slavic cheekbones, the gold-red hair—is livid, his face reflecting rays off the tucked-in body on the bed, whose carefully splayed limbs wait under the sheet, as if in anticipation of death-as-masseur. His eyes hook the younger brothers’ eyes in a kind of hateful crochet. Murderous words like ‘inheritance’ hop in the static.

The title poem, “Declare” is a lyrical retelling of the two first “joyful mysteries” of the Catholic rosary, the Annunciation and Mary’s visit to her cousin, Elizabeth:

the two of us mothers circled in a hoary girdle, like a cat’s cradle, blushing at each other, our bellies brought into contact, kissing, me sensing the rough spurt of the one who is before the one he is to go before

The use in this poem of “rubicund”, which also features a few pages earlier in the intriguing “Leaving Glawdom by night–”, was one “rubicund” too many for me. The same minor point can be made about the repetition of “disembarrass[ed]” on pages 22 and 30.

Clarkson demonstrates her range in the brief and poignant “Brother”, the quirky “In Bushy Park”, and the surreal “Violette, Michaela et al, according to Mildred”. Although this poem has been singled out elsewhere for praise, a heavier touch is displayed in “Three Young Surrealist Women Holding in their Arms the Skins of an Orchestra, 1936 – Dalí”:

Her life shrunk now to two needers who dominated: her mother and her daughter. Her music no more than a cipher

Clarkson’s poems that take a more conventional form are no less distinctive than the prose poems. In “a young woman undressed me and”, the repeated disrobing of its helpless narrator is three parts medical (“we’ll get you undressed and then / we’ll see to that”) and one part sexual (“she touched my lip with a shapely thumb— / shhh, don’t fret. her voice like jinxed june breezes / in lime leaves.”).

“Before the Match” draws on a ceremony enacted by Dorothy and William Wordsworth on the morning of William’s wedding, whereby her brother slipped back onto Dorothy’s finger the wedding ring that she had worn through the night. The poem is both tender and oddly sinister. Dorothy sees the fiancée in the ring’s “grab of gold and emerald”:

her leaf-mould eyes—her thin waist—

her black rope of hair caughtlike a noose on the neck

of an errant stallion—

her bell-voice calling out toBilly, Billy, for help, but he’s stepped aside

to visit with me and is saying, Dear Sis,

things will be as they were.

There are many other memorable poems in the pamphlet, including “Love Cow” (which Clarkson discusses here), “Edwardiana” and “His Wife in the Corner”, as well as two, “Bus to Piura” and “The Retirement of Madame Poulay”, which are somewhat less complex and subtle than the rest.

Shearsman have produced a visually elegant book, its attractiveness increased by the cover image, a detail from a 15th century painting of The Annunciation by Jan van Eyck. Overall, this pamphlet is highly original, technically inventive, and emotionally satisfying. It deserves a wide readership.