“Everything is within the context of the paper”: In Conversation with Joseph Makkos

-In Conversation with Claire Trévien–

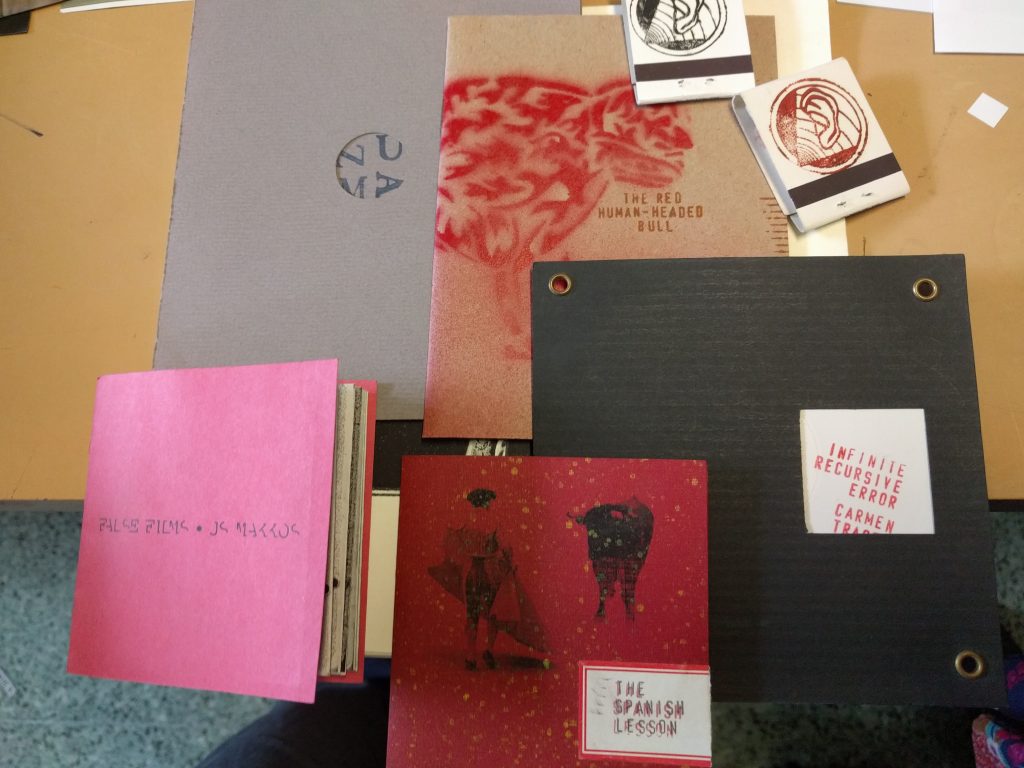

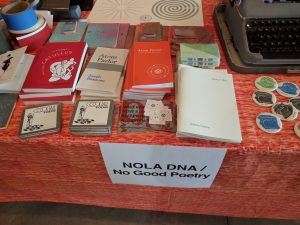

I was lucky enough to attend and review the second New Orleans Poetry Festival last month, and found myself drawn to Joseph Makkos’ stand at its independent publishers’ book fair. His stall included a poetry drinking game, cassette tapes, chapbooks, notebooks, and more (see photo below).

Makkos kindly invited me to his studio to look at the work he’s created over the last few decades and chat about ephemeral publishing. The morning of my visit, he was recovering from the New Orleans Poetry Festival secret after-party he hosted here: “You’re seeing the wreckage of the party last night, I didn’t clean it up because I thought it’d be a good landscape to photograph things on.” [It was]

The front room of his studio is full of salvaged technology which Makkos has been gathering over the years. There’s a curated section, where he puts together an office situation per era, one for instance features a “Late 50s IBM typewriter, I have a new ribbon for it, with vintage paper from the same era, desk from the same era, along with some jokey stuff to go with it, like Dr Strangelove here – somehow it works. It all fits in as a look.”

“I’ve collected this stuff for ten years, since I came to New Orleans from Cleveland. I really focus my searches these days, these are just things that came my way. Typers have gone up in price, particularly mobile ones, the ones with a little suitcase. I like these ones [indicates curated section] because they’re more officey/vintage/mod era. I am going to do an exhibition at some point.”

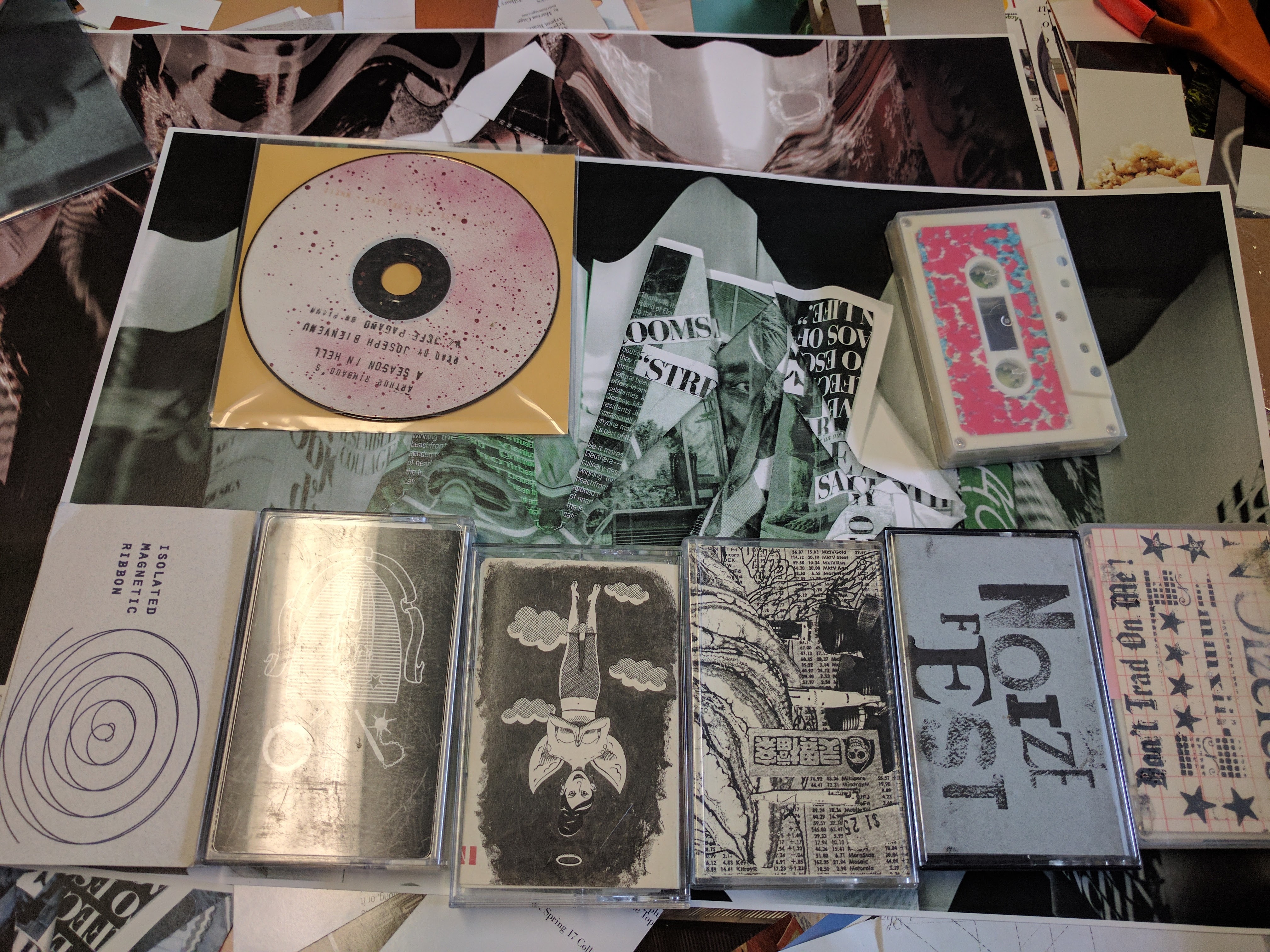

At this stage we are briefly interrupted by the appearance of Joseph Bienvenu, a long-time collaborator of Makkos, whose name will crop up time and time again when riffling through Makkos’ back-catalogue. While Makkos suggests places for them to grab lunch, I am allowed to look through the cassettes and CDs, which includes Bienvenu’s translations of Arthur Rimbaud’s A Season in Hell, accompanied by Jeff Pagano’s music.

As Makkos returns, I wonder if enough people still own the technology to play cassette tapes with, but he says the format is still popular. “There’s lots of different scenes of people that I’m in the circle with, and this is their chapbook. They sell them at gigs. When I do a tape for somebody, I make 60 or 100 and I keep 5 or 10 for when I do events or have a table at a fair. It’s all small run, small market. It’s not a huge mass production thing.” Creating ephemeral objects for events is something Makkos specializes in. For Noize Fest, he also made t-shirts on the spot for punters. “They were designed and printed at the event which they can take home with them and put it in the dryer so that the ink sets in.”

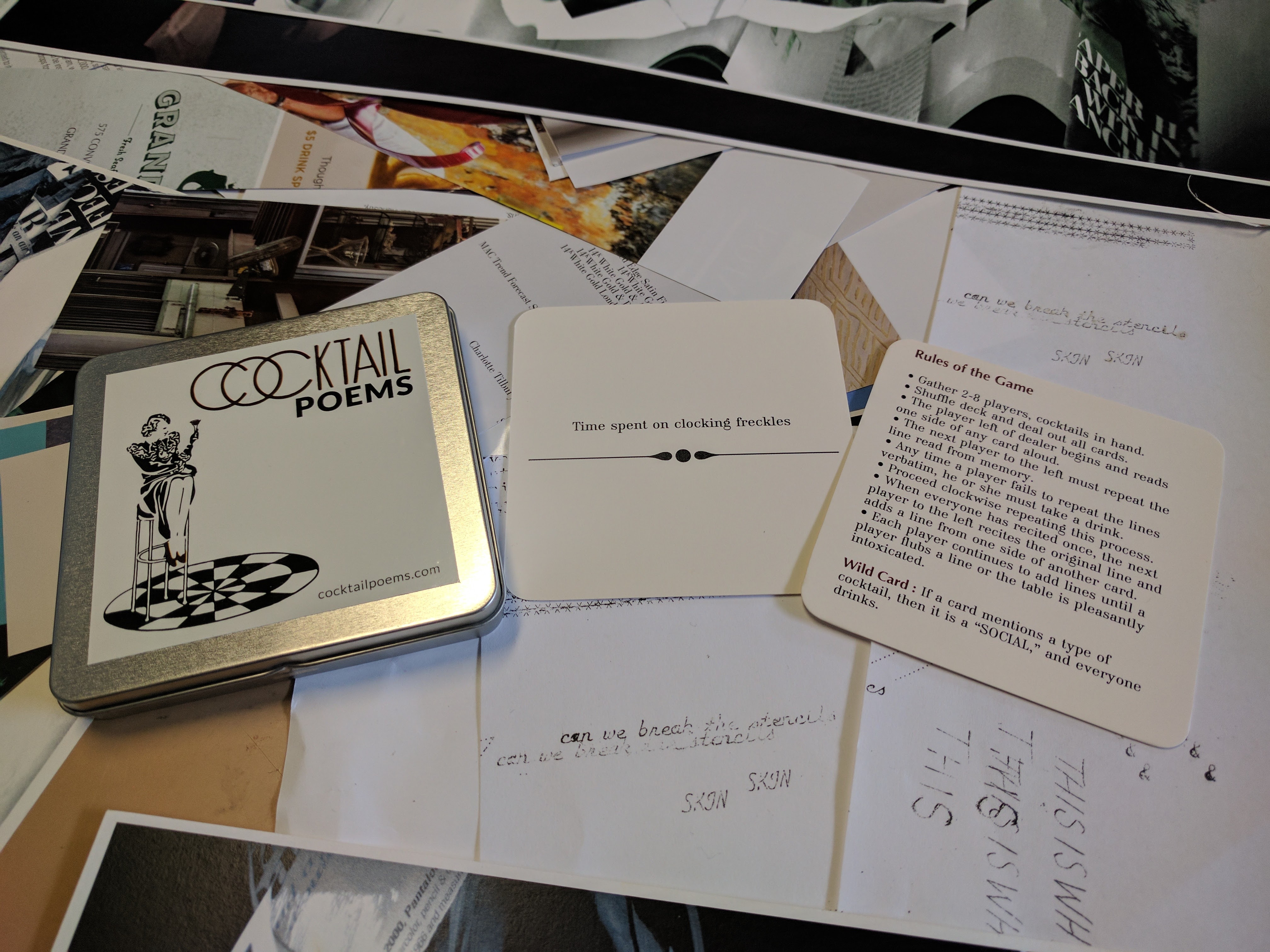

Makkos cracks open a box of Cocktail Poems, which I’d be eyeing up on the stand already. “It’s a drinking game”, he explains, “We had the idea of let’s do something more interactive. It all started with this poem of [Bienvenu’s] that I read, and it was really playful. So I read his poem and thought it was a drinking game. I had originally planned another game which was going to be a broadside you had to cut the pieces out of – we kicked that around for a bit, there was going to be rules, cards to cut out, and a game board and square pieces. We decided on this card format in the end, because we thought we could do expansion packs. We are still doing that, and have narrowed it down to a couple of people, and maybe do a poet every year so that it can keep growing.”

As he continues to share objects he’s created, such as the accordion-shaped False Film intended to work as the score for his 10 minute poetry reading, I have to ask: what unifies all of these different projects? “It’s really about paper. This all came out of wanting to create beautiful art objects, but doing it with people’s work. How do we turn these works into an object that makes people go “wow what’s that?” and do it in a cool way and present it in a way outside of the whole digi-packed, shrink-wrapped world of faux-gloss printing?”

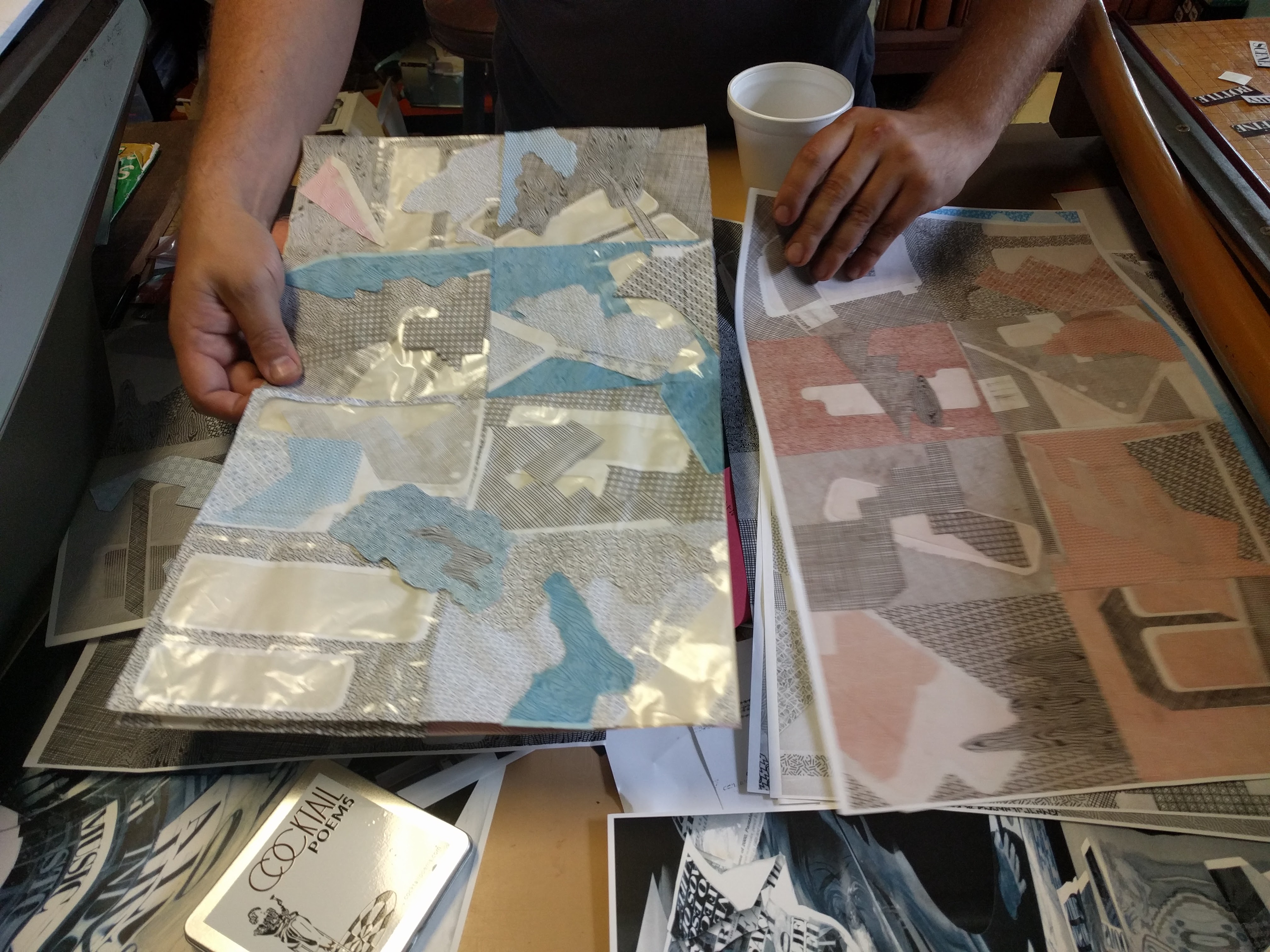

“Sometimes I compose a project through the paper. I try to dream up something to make with this paper, rather than dreaming up an idea and figuring out how to print it. Like this one started with these mail envelopes. I found these envelopes and turned them into enclosures.”

He lays out a series of chapsides he made, which also started with paper: “This is a pure example of starting with paper and working my way through. Someone gave me this giant stack of super beautiful thick 100 pound speckled paper. 8 ½ by 14 – this was given by a dye cutter who had extra paper. Everything is within the context of the paper, and its size. It’s all very delicately designed, and it’s from the era when I was transitioning out of Cleveland. This aesthetic fits together – for me as an artist, it’s working through a process with different artists and helping them achieve their vision of what they’d like to put together and what they’d like to achieve.”

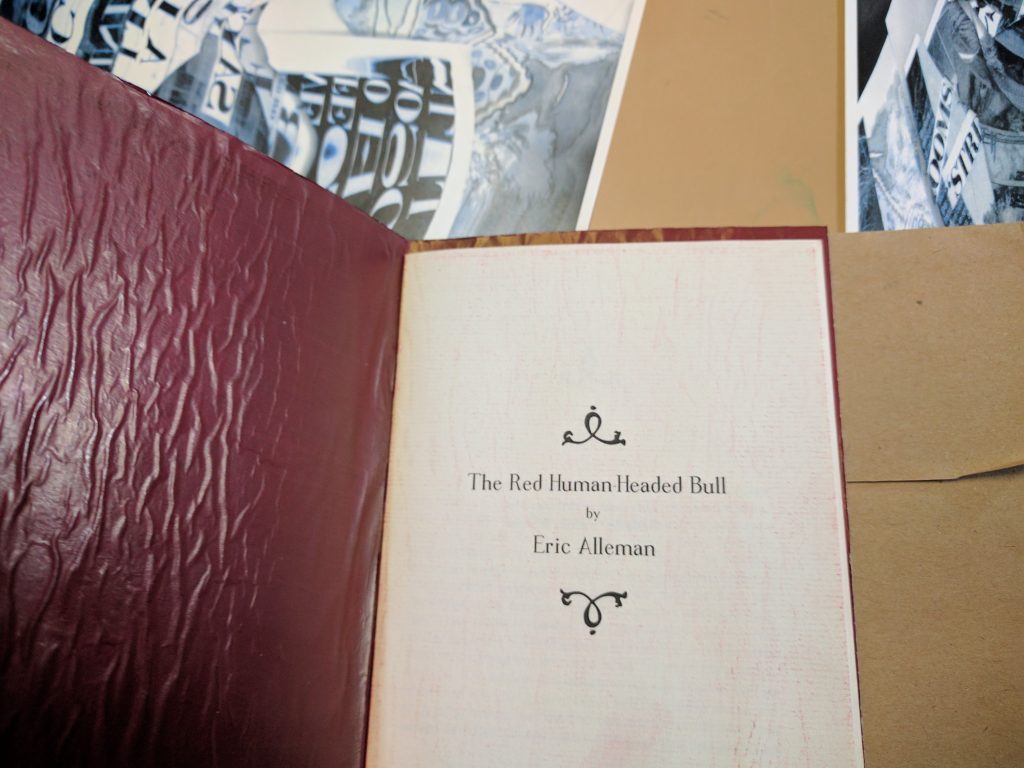

The papers he chooses also alter the very objects they make, as with the stencil paper used for the The Red Human-Headed Bull, whose red transfers on paper as the book is read, infecting and modifying it.

The names of his presses are all individually poetic and imaginative: Hobby Horse, Language Foundry, Makeshift, Sub-house, Variable Compass, Borrowed Time and Ink. “I keep them organized in my mind somehow. It’s the name I feel like putting on a project at the time.”

I have to ask about his podcast series No Good Poetry, hosted alongside Bienvenu, which they recorded during the festival too. “Joseph and I conceptualised the idea of doing a podcast that tackles other topics to poetry, like we reviewed this movie Patterson, we did political poetry, and now we’re doing a DADA poetry one, there’s a New Orleans Poetry Festival episode. We have a dozen figured out, then we’ll take a survey of what worked and change it up for the next dozen. We’ve done some recordings on poetry and architecture and how it affects visual poetry, we talked to a video game designer about how poetry and video games are similar. We’re interested in things like that. This is stuff that other people will listen to who aren’t necessarily interested in poetry.”

Finally, how would he describe the New Orleans Poetry Scene? “There’s a lot of different things going on, there’s a slam poetry scene, there’s an academic poetry scene, a silly poetry scene. You saw a few of those elements interact at the poetry fest this year, maybe 3 or 4, and there’s around 7 elements of poetry here. To put on a festival that permeates every corner of a poetry scene in a city is really hard. So the scene is quite expansive and has different identities, from youth poetry all the way up to Poet Laureate of Louisiana. I interact with it semi-regularly, I go to readings maybe every other weeks. The Cleveland scene was pretty tight-knit, you knew which readings to go to every week. You knew who you would see at each reading.”