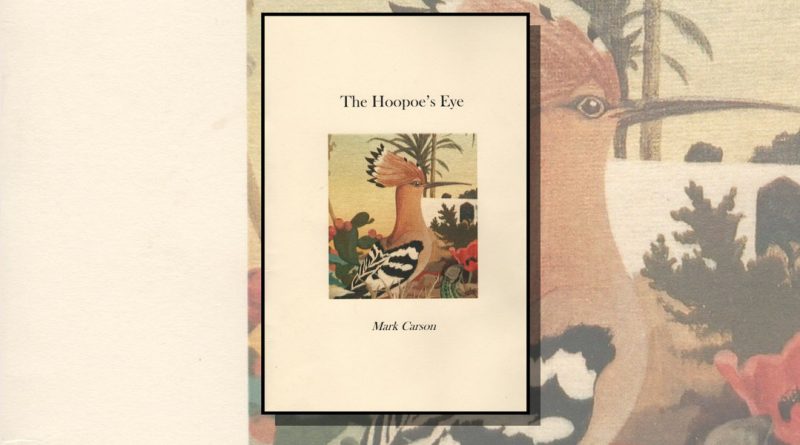

The Hoopoe’s Eye by Mark Carson

-Reviewed by Stephen Payne-

The front pages of this pamphlet reproduce a letter the poet received from his neighbours in Andalusia, where the poet owned, still owns I assume, a house. The letter describes a natural disaster — the local river (the Guadiaro, we are to learn) has flooded and engulfed the village.

The first poem in the pamphlet describes this flood, by focussing on ‘The New Footbridge’ that was built across the Guadiaro shortly before the flood happened (“It springs across the river like a slice of rainbow.”). As in one or two other poems, Carson’s expertise in engineering informs the poem, for the better:

Who could imagine the buoyancy of timber?

Who would consider the drag loads on the structure?

Who did the sums on the piddling little brackets,

the tension, the shear, the bending and the torsion?

“Piddling”, I suppose, expresses the resident’s anger breaking through the engineer’s curiosity. If so, it’s a rare example of expressed anger: the accurate physical detail is much more the modus of the collection.

Alongside the language of mechanical construction ‘The New Footbridge’ occasionally presents in a classical voice. We’re talking about a flood, after all:

The goats and the sheep retreated to the hilltops,

watched as the racing spate tore the banks asunder,

watched as the carcasses were tumbled down the valley

The second poem describes the author’s arrival at the scene of devastation. ‘Nothing prepares you’:

for the gap-toothed river bank

the fig tree swept aside

[…]

You’re forced to force

an entrance,

something gives,

something cracks.

And then, after these two poems introducing the crisis, something remarkable happens: there’s a ‘Riverside Picnic’ in which the strength of some local young men is viewed, at first wistfully, then gratefully as they pitch in to help. Recovery begins and gains momentum: satisfaction and hope are found beneath the layers of silt or in a fly-past of large birds in the sky from where the trouble first arrived.

“Poetry is the subject of the poem”, wrote Wallace Stevens, and there’s an unusual kind of truth to that here, not because it’s Carson’s main point, but because poem after poem finds joy in objects or creatures that were out of sight, hidden in mud, before the episode of their rediscovery and the close attention that rediscovery entails. Cleaning the mud from a simple object is what many contemporary poems do, metaphorically, and it’s enjoyable to read about it being done so literally and evocatively as well as to admire the mental resilience the work must have required.

The title poem is an excellent case in point, and it’s beautifully celebrated in the cover art by Betty Luton White. A painting is discovered under the mud, in the worst way: “A pistol shot explodes beneath my heel./ It’s glass. A naked wall…” But when it’s dug out, the next morning: “a hoopoe’s eye, bright as the day it was painted,/ brighter than ever I’ve seen it”.

Also found in the mud are some olive picks (“a baby carousel”), a set of ceramic tiles including “the lizard tile,/ its S-bend curling off/ across the crusted mud”, a real snake, and a real gecko, delivered “back to the river/ which only last week dropped him off”.

The final poem describes, in a mimetic long-lined sprawl of colours, smells and textures, how, on the village ‘Feast Day’ a giant paella was cooked up and served. “This is how it used to be” the poem begins, and one might expect that loss to be acknowledged more directly, rather, through its sensuality, the poem affirms the hopeful message of the whole collection: “they fed a thousand people in less than ten minutes and by god it was good,/ a paella to remember.” Surely, this is how it will be again.