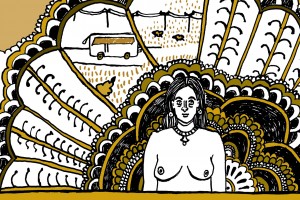

True Tales of the Countryside by Deborah Alma

– Reviewed by Sarah Hymas –

True Tales of the Countryside is a pamphlet of self-discovery, and a wry celebration of adult independence. The introduction (by Helen Ivory, whose recent book Waiting for Bluebeard covers similar themes, albeit very differently) lays out the book’s exploration of feminism and identity, the power of language and folklore. The introduction is an unusual addition, albeit one that features in all of Emma Press’s pamphlets so far. I’m not completely sure of its necessity, but it does throw open doors to connections between Alma and other writers, in a chatty, intelligent and informed way. Perhaps the introduction will encourage fans of Ivory to pick up the pamphlet, and perhaps fans of this pamphlet will pick up Ivory’s book.

I turn to a pamphlet for small scale intensity, the ability to breathe in an often thematically linked run of poems without being overwhelmed by ‘too much’, the poet presenting her best work in one unit. Just under a third of these poems have been published elsewhere; I’m not surprised. They are potent and self-aware, inclusive (to this reader), and are able to sound flippant but never facetious. The overriding sense is of pain transformed to anger, transformed to wit. This energy spits through the pages, perhaps nowhere more evident than in the first poem, ‘I put a pen in my cunt once’. This poem presents the creative potential of a sexuality that is both confrontational and tender, ultimately freeing. And on this the pamphlet rides…

The first eight poems consider home from a range of angles: sex, bedtime rhymes, fear, safety, dislocation, claustrophobia. There is a repeated undercurrent of unhappiness, and the attempt to articulate it exactly: through metaphor, perverted nursery rhymes and fairy tales, and, perhaps most effectively, through raw, unpunctuated language:

I am drawn instead to my own songs to let them sing in the fresh air

love letters to myself wearing the blue slip with the butterflies I take up

the pretty teapot for one the scratchy pen the days the life floating

lonely happy and sad

These poems stretch the menace lurking in fairy tales into the supposed ‘happy ever after’ of a real marriage which makes for wistful, bleak reading. Then they mock themselves: a narrator is accepted into a friendship group by adopting fridge magnet aphorisms. Elsewhere, in ‘Getting It’, she experiments with sex with a space hopper, an old friend and swingers. It is, even in 2015, refreshing to read of such light-hearted joyous pursuit from a woman; especially as directly after this comes a strange choice: a poem in which the narrator, sounding childlike, invokes Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz.

I love my red shoes;

all of the shows I have loved,

they are.

I swing my legs against the wall,

scuffing them slightly.

This could be unsettling in proximity to the wild tempestuous sex of the previous poem, but because of the control in the authorial stance of both poems, I read it as heralding how women can be promiscuous and wistful, adult and child, bewildered and centred.

‘My Mother Moves into Adolescence’ marks a sea change in the book. No fairy tales lace this poem of six parts. Each part simply presents the mother’s request followed by the daughter’s response, each growing in tension, the language becoming more and more terse, yet never breaking the veneer of calm structured sentences, coherent line units.

After this pivot, the book switches to a tender, loving tone. Sisters and lovers treat each other kindly, with care. ‘She describes herself like this’ embraces simple achievements, and is touching, warming and affirming. All very twee, perhaps, until it manages, unhurriedly and integrally, amid the other faces of love and identity in this poem, to end with orgasm.

The title poem presents sections of seemingly disparate narratives of rescue, warning and transformation, then reverts back to clean, unfettered descriptive language. It celebrates living amongst the natural world, our impact upon it and, in a most haunting use of moleskins, how it affects us. What is nature? What is our nature? are subliminal questions that run through this pamphlet. It doesn’t attempt to answer them, just asks again and again. This insistence anchors Alma’s humour, her folkloric references, and adds a resonance to the poems, sets up their interdependence on each other, so that they reverberate beyond their individual forms.