Father, Husband by Scherezade Siobhan

– Reviewed by Owen Vince –

(Content notice: this review contains material on rape).

In her essay ‘Not Safe for Porn’, Mia You writes that

poetry can provide description, delineation, repetition, affirmation – but also inherent in poetry is the possibility of abstraction, and this abstraction can conceptualize, circumnavigate, shift, [and] relineate what we see as the limitations of our physical forms

Poetry, she says, “is the tension that arises”. Likewise, Jennifer Ashton writes, in ‘Totaling the Damage’ that the face, “more properly, the practice of recognizing the face and giving it form”, is the work of poetry, its primary sensibility, its “goal”. In Father, Husband, Scherezade Siobhan presents bodies which rise from formlessness and disperse into form: bodies, and the histories of bodies, as transactions in language. Trace the contours of a statue with your fingers: it goes in, it goes out. “Form” as both presence and absence.

Siobhan presents the poetic subject as a series of bodies, plural, which arrive and depart in the collection’s language; a body that is always already many bodies. In her dedication, perhaps the most revealing and personal I have read (and I do read them, almost rhythmically, automatically), is a father “whose absence convinces me that love is a verb best rendered in past perfect tense”, and a mother “whose presence convinces me that hope is a verb best rendered in future continuous tense”, belonging to and shaped by language.

“This book is a woman spelled as saudade. An echo of inheritance, a past that runs in future continuous tense”: Siobhan slips from tense to tense as if stepping from stair to stair, presenting a wild cartography, a height-map of contours and reversals. The perfect noun is discoloured, transacted. Detached and bolted again to a different construction, “saudade” is melancholy longing. It is not quite a proper noun, for it doesn’t bear a capital: a self that is not a self (surely that is a better definition of “longing” than the teleology of simply “wanting”?). The “you” addressed in the poems arrives and departs and refuses to attach to a particular subject, and this works. The poems refuse to solicit an easy understanding. We’re in a language world in which bodies are not actually here, but rather are given to us via language. They are absent – but then we see them.

Siobhan’s dialects, references and lexicons are vast and complex, asserting the difficulties (and exciting possibilities) of translating across a language surface. A body or bodies are transacted through a common tongue that asserts it is also uncommon, “exotic”: unfamiliar words slope against familiar words. The first poem, l’tranger, asserts a particular, specific state of being (“abroad”), and its literary subject, Camus, whose l’etranger is only a slipped vowel away, then asserts another, his compatriot, “hiroshima, mon amour”, the title of Alain Resnais’ 1959 film. Siobhan confronts this slipping subject: “what is this city, where is it, & who are you / in this city?”. Father, Husband is about such locations as de-locations, acts of finding which transform into acts of (linguistic) abandonment. Resnais’ film probes the question of love and contact across a febrile, fragile cultural divide: “I came to leave”. In coming to leave, we witness the possible depths of this language; “oxytocin”, “matryoshka”, “kilims”, “alif”, “laam”, “mim”, the “honeycombs” plucked “out of the alphabet”. Borders between languages (and cultures) dissolve through combination, unfolding a fragile ethnography of love and bodies, an anthropology of communication.

The body is written through this world, and onto it, in languages which are just beyond decipherment –

you tell me how it all began with a desire

to compose the cartography of heavens

the first mapmaker contoured a cobweb of

constellations in the cave-mouth of Lascaux

The poetic urge is represented through pre-historic expression, in a deeply honey-combed language. I want to say that Siobhan shares something with Lawrence Durrell, who also foliated and intensified his language, chased it and the shadows of people – friends, lovers, aliens – through a mixology of discourses and registers: Greek, English, French, Arabic. Siobhan makes assertions, only to vaporise her assertions back into language. This should confuse, but actually it clarifies: “i am a woman, / stolen from / symmetry”. Verbs dance and vibrate with their own intense energies; “we slake in a / confluence / of seacoasts, we slumber in catastrophes”. Siobhan reassembles nouns and verbs in ways that produce new stems and roots: reassembly as growth, and as wild experiment.

I rarely sit down and just read a collection. My attention wanders as the languages settle. I need to let them – steep? Father, Husband stayed open. I continued reading. I think the sun set, or rose. It’s a big collection: the pages create and sustain a rhythm which adds layer upon layer of language, a sort of delicate sugar construction; an architecture of glazed strands of sugar that somehow support the weight of entire people, office furniture, light fittings, cars, animals, champing horses, film cameras. This piling is appropriate because it is always done delicately, with a keen sense of the kinds of electric (and eclectic) sparks that language creates when brushed against itself. It becomes involved in discursive activities of language and language change:

this is how you become / a dexterous anagrammatist

/ if you rearrange rape, you get pare / to peel, trim,

carve / you drag the knife across the stomach / of a

syrian pear

Here the body becomes implicated in fruit, as if to subtract from the violence of that act upon a body, but the association of “stomach” with “pear” reasserts a subject, a self as victim of the rape previously mentioned, even as language attempts to deny and extract itself from it. Siobhan demonstrates that discourses – the words we use, and how – attempt to deny specific narratives (such as rape, and violence done to female bodies), but shows that the violence is still there, revealed in the language. Sliced fruit becomes sliced body. They are the same. Mia You’s “tension that arises”: the words we choose, and the relationships we construct between and through them, are not neutral. The voice offers us an anagram, but in doing so, in moving away from the original word (“rape”), poetry as metaphor brings it hurtling back. Siobhan shows that language is a deeply political and sensitive manoeuvre. She is a careful host and guide: we are not simply looking at a forest of constructions. We are looking at the work of construction itself.

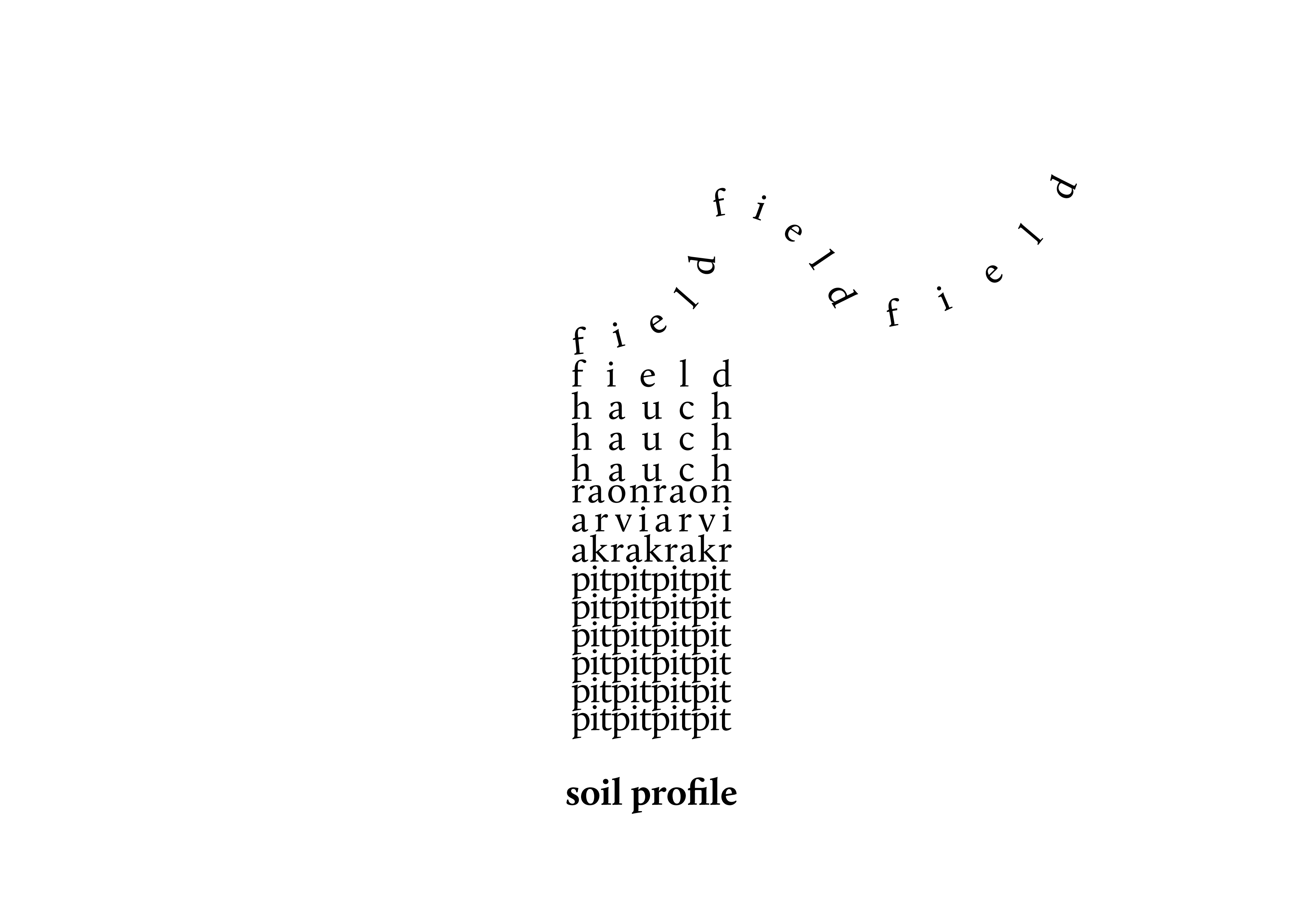

These involvements in different forms are exciting, as language writhes like a cut-off electric cable; repetition and lists are used effectively because they highlight sides of the language that are not present, but alluded to. In “Annulment/Excuses”, we are provided with an expanding list-poem of explanations for a question that we have not witnessed:

because the weather

because the alarm clock divorced the almanac

because the last bottle of milk went sour

because the dogs held an overnight concert in the

stadium of trashcans

Other poems are dreamy and hazily mystical; they are almost epigrammatic, such as “time dehydrates my dreams”, or “a man with more sorrows / than the octaves of ochre-winged parrots”. Selves pursued through the poems arrive and depart like shadows on a wall. I kept thinking of the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico: orange, sun-baked squares at sunset. Tall, ochre buildings casting musky shadows over empty, parched ground. Figures standing together or apart. It’s as if we’re about to understand something, or we have just missed an explanation, arrived too late. Language rhythms through the subject that is the lyric “I” but also “she”, “you”, “her”, “he”, tense and pronoun jilting and jumping. “I watched her being spat out like smoke from a / coughing kiln. She is stubbed out in an imprecise / stain, a secret scar”.

The energy and intensity of this poet’s metaphor is exciting, tearing through the consume cupboard of a language, combining eclectic pieces in transformative outfits. We’re not being drowned in language; we’re being buffeted and arrested and exposed to language as something that can be simultaneously stable and unstable, as it slips and eddies around particular bodies, and memories and locations of bodies, evoking both Mia You’s “tension” and Jennifer Ashton’s sense of poetry as a form attempting to find a face. Father, Husband is a diverse and electric investigation which subsumes and excites the reader. We are on the building site, at the brick kilns, at the quarry, at the opening of the architecture of Siobhan’s language. Father, Husband manages to simultaneously construct and deconstruct language, as it attempts to locate itself among a world of possible bodies, using anagram and metaphor as dynamite and stiletto knife. Destruction and quarterization. What remains is the stimulus of the action itself: “i will summon you to this deep beaujolais of my mouth”.