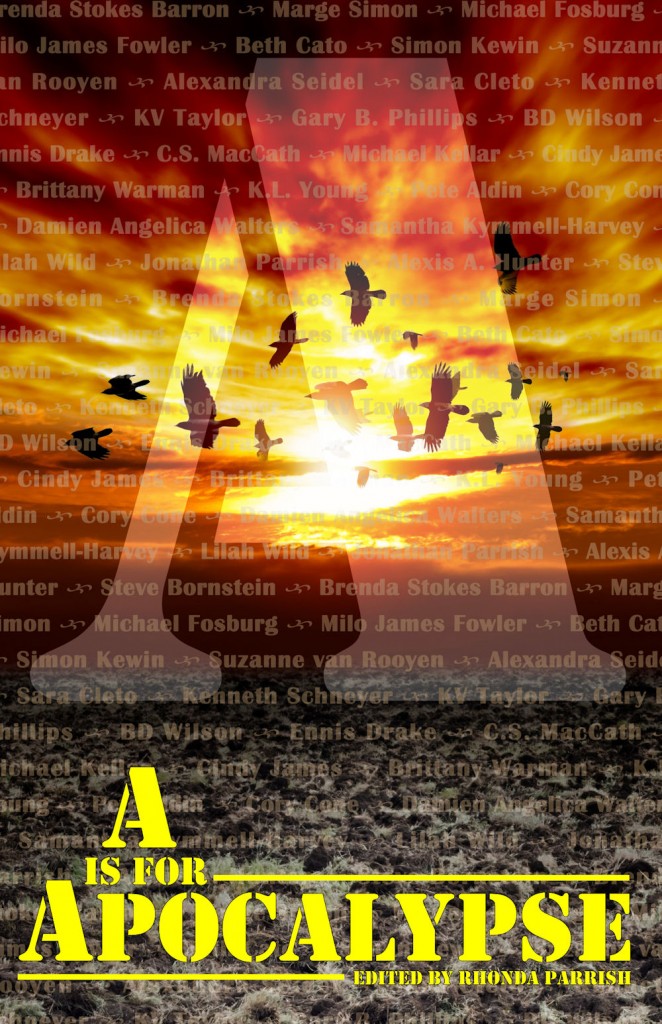

A is for Apocalypse (ed. Rhonda Parrish)

-Reviewed by Nick Murray-

I have no idea how big Godzilla really is. During his atomic inception he was 50 metres tall and exactly relative to the Tokyo skyline at the time (the tallest building being the National Diet Building at 65 metres). When I joined the kaiju craze in the late nineties he was still relative to the urban landscape’s tallest buildings, so our titular megalizard was bigger too (90 metres). What am I getting at? It’s a question of scale. Godzilla always has to be just a bit bigger than you could possibly imagine a creature to be. That forty metres is the difference between a creature feature and an unstoppable force of nature.

As our scope gets bigger, the huge things of the past get dwarfed. The importance and impact of previously looming entities fades. This is an important factor in the apocalyptic fiction genre. Up until the 90’s apocalyptica was a vehicle either to reference bigger social issues (Romero’s Dead series) or as the byproduct of an antagonist’s goal, still relatable on an actions-of-a-living-thing level, for the hero to fight, like Will Smith in Independence Day. Here the impetus is not that the world will end. More ‘Are you a bad enough dude to rescue the President?’ But neither made much of the crushing fact that what was happening was inevitable and not so removed from quite possible. (Not actual zombies. It’s a metaphor, geddit?)

It took some years before the apocalypse itself would take centre stage. As the trend in global concerns shifted towards more environmental issues and pop astronomy really showed us how tiny and powerless we are in the universe, the scale of things expanded and a genre was given space to emerge. The apocalypse genre is a question of scale. Character pieces don’t quite fit. That’s not to say that character led stories are bunk. The most striking stories in A is for Apocalypse take place on a very intimate and human scale but through the despair of an individual they paint the suffering of an entire world. Much like the impending final stroke that all the stories are warning about, the genre of ‘apocalypse’ is at once both a very broad one and a restrictively narrow one.

The apocalypse can become subject matter or setting, leaving the story to be something altogether different. For example, the very first story in the anthology is a straight horror piece about a shapeshifting tower of human sacrifice which reads like ‘Lovecraft-lite’. It takes a couple of stories for the book to hit its stride. The third entry, ‘C is for Coyote’, feels like the first ‘proper’ piece, after a couple of warm-up entries. A brilliant idea and a clever setup make for a story that goes from written-out video game to tense supernatural thriller in three paragraphs. However, this story of survivalist rednecks and body-hopping spirits is no more apocalyptic that the two stories previous.

‘Why so pedantic?’ I hear you sigh. ‘What’s with all the genre policing?’

Well, my finicky attitude to A for Apocalypse comes from the editor’s introduction. Rhonda Parrish witnessed an anthology film called The ABCs of Death. In a bolt of creative fury, she decided on a literary equivalent.

And so this alphabet anthology series was born. It doesn’t have an official series name, but in my mind I refer to it as the ABCs of Awesome.

A is for Apocalypse is the first in what is to be a series of twenty-six anthologies, each containing twenty-six stories.

Parrish’s project is an ambitious one. Twenty-six books of twenty-six stories each on twenty-six different genres. Not to mention the alphabetised titles to accompany each one. It’s a big idea, but I admire the chutzpah behind it. It can be done and I’d certainly dip into the series for genres that caught my eye. However, a series with such a tightly woven theme needs to be orchestrated somewhat holistically. At least a handful of the genres need to be set in advance and stories placed as they come in. Opening with the mission statement of a definitive genre series leaves A for Apocalypse open for contextual scrutiny. I found myself assessing the apocalypseness of each story instead of enjoying it for its literary or narrative merits, a task made even more hairy by the split in the book between sci-fi apocalypses and fantasy ones.

While some of the writers fall onto the zombie trope for their ends-of-the-world, and a couple even bring in vampires and werewolves, many of the stories in the collection are brilliantly inventive pieces of fiction. ‘F is for Finale’ paints a grimy scene of a composer, long gone into madness, who has locked himself in his apartment to write his magnum opus before the world finally ends. Suzanne Van Rooyen builds a fantastically claustrophobic world for the protagonist which is both his room and his mind.

Gray sunlight filtered through the cracks in the boards nailed across the windows. He dared not stray too close for fear of the radiation corrupting his mind. His mind, his thoughts, his music – it was all he had left as the world disintegrated, succumbing to rot and ruin in the wake of the catastrophe.

This is a cleverly unhinged story of a man losing his humanity. There are two hints of the outside world, which come from other inhabitants of the apartment block trying to bring food. The story could have swung two ways here. If the voices outside never mentioned the ‘evacuation plans’, it could be implied that the whole apocalypse exists entirely in the protagonists head. By making the peril outside real, it diminishes the impact of what is going on inside the room.

The uses of the apocalypse are wildly varied, which brings some unexpected flavours to the collection. Two well constructed ends of the spectrum come from ‘Q is for Queen’ (Brittany Warman) and ‘N is for Nanomachine’ (C.S. MacCath). The former is one of the shortest pieces in the book, but is one of the most considered. Following a handful of dishevelled worshippers of a mystic queen, the story perfectly sets up the few minutes right before the world is plunged into a blood and hellfire fantasy end. The latter, is a science fiction take on the genre. A planet of synthetic people (it would be reductive to use ‘beings’) face an inevitable extinction at the hands of the human race, who created them in the first place. It is told from the perspective of a scientist, a painter (who together are a couple), a poet, a composer and the head of state. Through letters from each of these characters you are given access to the beautiful aspects of life, which makes the inescapable climax all the more unbearable.

The most arresting story in the anthology comes from Damien Angelica Walters. ‘U is for Umbrella’ is both the most fitting piece for the genre and the best example of how to utilise it. Following a mother and her daughter during the last fourteen days before a meteor hits Earth, Walters manages to capture both the humanity of the situation – normal people coping with despair – and the heroism that emerges when faced with adversity. There are no other people in the story apart from a silent neighbour and his dog, and the story take place almost entirely in the same two or three rooms of their house. Using this reduced setting, Walters perfectly shows the hopelessness of an entire world.

That’s what it’s all about at the end of the day (no apocalyptic pun intended). Something smaller becoming the representative for everything. One house becomes every house, because every mother inside will be looking at the sky wondering how it’ll all end. Every tornado, earthquake and flash flood becomes embodied in a giant lizard. If you can see it, you can comprehend the power within. The size becomes an illustration of what could really be round the corner. Let’s hope that the same is true for Rhonda Parrish’s anthology series. A is for Apocalypse is a showcase of some first class fiction, and is packed with potential for the series as a whole.