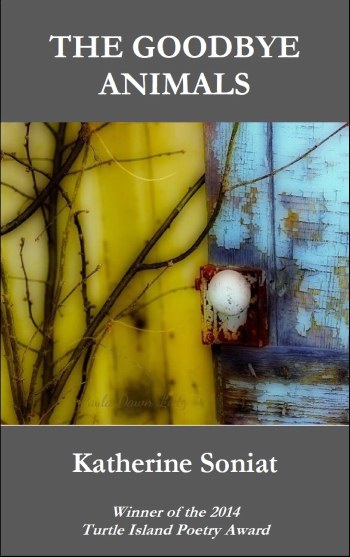

The Goodbye Animals by Katherine Soniat

– Reviewed by Alice Allen –

A pleasingly bound and hand-stitched chapbook of thirty poems, The Goodbye Animals won Katherine Soniat the Turtle Island Poetry Award (2014), run by a journal whose submission guidelines ask for poems that ‘explore and aim to deepen our connections to the natural world’. The poems in this collection go several steps further, intent on exploring different states of human consciousness and their orientation within nature.

Throughout, Soniat pays her respects to key figures in the quest for perception beyond ordinary sight. She opens with a quote from Black Elk: ‘I saw more than I could tell and understood more than I saw’, refers in one poem to the Third Eye, and in another to the deity Kuan Yin, whose name means ‘observing the sounds of the world’. But beyond these signposts, Soniat’s poems, with their accomplished and restless form, and their exploration of liminal states, successfully scrutinise our connection to the natural world.

‘Fire Devotion’ starts with the moment life begins – ‘cells / vibrant in the amniotic pool’ – and unspools in measured but fragmented lines encompassing birth, sex, the movement of time and the development of the mind. The poem steps lightly among these weighty themes using tangible, arresting imagery:

Curled in water, the spine perfected. Fetal and

blind, I bow.

Far from being didactic, the poem, through its broken lines, pauses and spaces, unlatches complex thought and sets it adrift:

Our cold lineage, space. Friction and flint,

darkness set afire.

Slowly then knowledge arrives as only

and once. Distinct. Solitary.The intimacy of time.

The poem does not prioritise human birth over any other creature’s beginning, moving seamlessly between human, tree and bird:

And ahead, that promiscuity called November.

Naked limbs. The orifice. Sap configured,the same over

and over.

So it is with ghost strata in the canyon and the mating

hawks of spring –

This inclusiveness seems central to Soniat’s understanding of the world, in which our human position is far from superior. Cruelty and violence towards animals is presented in poems such as ‘browse’, which charts the death and beheading of a deer. In ‘The Animals Go Up’, war falls on animals as well as people:

limb by limb a people

come apartKilling the daily chore Bodies gutted by a brook

Roof walls fields and the animals

go up in smoke

Soniat often writes about subjects outside of language: the developing foetus of ‘Fire Devotion’ is on the brink of consciousness, and several poems explore the mind as it flounders in a body fading before death. Soniat writes with the precise, stoic clarity of someone who has kept vigil by a bedside, and her poems about dying are incredibly moving. In ‘Kuan Yin Disappears’, the process of a life leaving a body is made visible:

At night in the sterile bed,

he struggles up and down, sometimes in a river –mostly in the farthest reaches of his brain.

In ‘Stillness’, a man’s last hours are laid out with unflinching detail:

Sound disappearing, his vocal cords

sighed a bit – the syllabics of this life, done.

The speaker is listening-in to the last sounds before death, the mind still alive but detaching from language and disintegrating.

The final poem, ‘Silver’, also draws on mental disintegration. Divided into five sections, the voice in the poem seems to billow in and out of different states of mind like the movement of the wind or the sea:

It’s only fitfully

I see now (and again) in a rainy season

where who knowswho’s singing oh my angel my

intricately tailored one

of late how flushed I am with you and this

the half-life

Obscurity runs concurrently with generous lilting language, the ‘all the way world wind’, for example, and the ‘frequency of whale’. The reader is kept bobbing along the surface with just enough tangibility to stay afloat.

Soniat makes specific reference to Rilke’s ‘The Eighth Elegy’, which seems crucial to her writing. To a certain extent, the entire chapbook can be seen as a resonant, explorative response to Rilke’s poem and its quest to look out into ‘the Open’, to see the world as a child or an animal does, to have before us ‘that pure space into which flowers / endlessly open’. Rilke writes:

A child

may wander there for hours, through the timeless

stillness, may get lost in it and be

shaken back. Or someone dies and is it.(Translated by Stephen Mitchell)

Reading these lines it is hard not to think of Soniat’s poems on the approach of death, and also the child in her poem ‘Another side of the Trees’, poking fingers into ‘her watered / forest home – she tastes mud and wears it.’ In ‘Extinction’, a woman’s identity is lost among the clamour of objects in a furniture shop, an extrapolation of Rilke’s claim that we are

…spectators, always, everywhere,

turned towards the world of objects, never outward.

It fills us. We arrange it. It breaks down.

We rearrange it, then break down ourselves.

Soniat’s animal poems echo the ‘vast gaze’ of Rilke’s animals and, speaking from the amniotic, echo the ‘bliss’ of Rilke’s tiny creatures for whom ‘everything is womb’.

Soniat’s work does not feel rooted to one particular geography. Hers is not a settled poetry of place, but has instead a scattered, agitating energy, ranging across many different mental and physical landscapes, at times cutting itself free from normal syntax, just as her subjects are often mentally dislocated or outside language. Restlessly pivoted towards death and isolation, the result is a collection nevertheless enriched with humanity, which may indeed allow us to see the world differently.