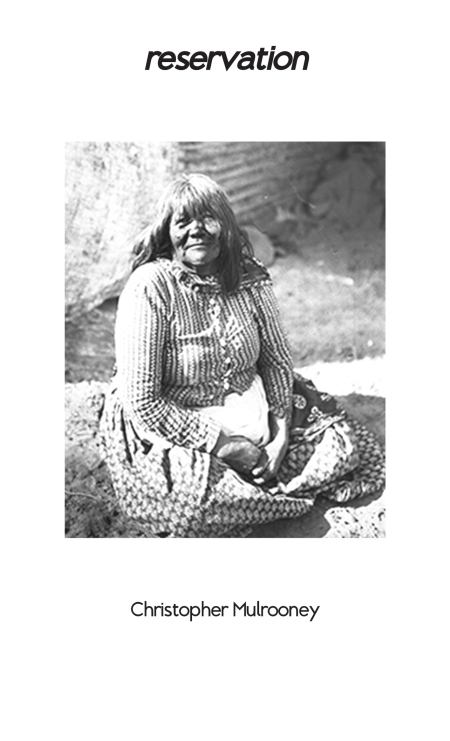

reservation by Christopher Mulrooney

– Reviewed by Grant Tarbard –

Christopher Mulrooney was a man of many talents: a photographer, translator, playwright and editor of LOS, among many other facets. His prolific work teemed with the places he loved: born in Athens, Georgia in ’56, in life he was an Angelino at heart, and fought for the depleting culture of the city. He wrote every day into the wee small hours: poems, plays, critiques. It makes one truly envious, but let’s concentrate at the poetry at hand. reservation (a tract of land set apart by the federal government for a special purpose, especially for the use of a Native American people), is a fine-grained curio, a thin pamphlet containing riches that outweigh the paper. Its cover image is of a Mojave Indian woman, circa 1900, smiling through the momentous and horrendous changes in the lives of Native Americans.

Mulrooney’s intriguing method for composing, his thought-dividing writing process, is infectious and keeps you hooked. At times it’s almost Nadsat, intricate. Some may drift off the page when their own thoughts lead them astray. It is a bit like reading Eliot’s The Waste Land in its hidden depths. His love of language is evident, playful, although very well constructed.

‘elle a chaud au cul’ (she has a hot ass? My schoolboy French is as rusty as a rake in the rain) is a poem about the sun, prevalent in LA, not so in deepest England. The reader can feel warmth from “the mothering sun” or it can be read as a little love ode, a hint into the weaved personal, as a kiss to the poet’s lips “laughs moustachioed in lipstick”. ‘Brokerage firm’, an unrhymed Glengarry Glen Ross quintain, speaks of our modern haves and have-nots.

here we have the far removes

a token interest in the company

The next three poems are after Mallarmé. ‘To Whistler’ is a mousetrap of a sonnet which can be read straight and beautiful: “black hat themes in swarms”. Whistler often painted himself with an assortment of black hats, from his pen and ink days on. I don’t know much about Whistler, but this could also be read as an antiwar poem:

apropos of nothing storms

just to occupy streets

black hat theme in swarms

To paraphrase Orwell, ‘there is always an enemy’.

but a dancing girl is sweet

Victory Gin as distraction?

And is this Dubya?

worn down

in wit drunken motionless

with a tutu lightningcrowned

otherwise not caring less

In any poem there’s scope for the reader’s rambling imagination, and Mulrooney knows this.

I am in love with ‘tomb of Edgar Poe’: we all die, the fall of the house of (insert your name here). Two quatrains and two tercets make up the poem, like Mallarmé’s ‘Homage to Richard Wagner’. Poe was buried in his grandfather’s plot in an unmarked grave, until the tomb, of which the poet speaks, was erected years later. I hear Beethoven’s 7th while reading this.

Mulrooney channels Poe through a Blakeian filter, with such wonderful lines as:

they like a vile hydrajump at hearing the angel

and

earth and sky are hostile oh the grief

if our idea withal carve never basrelief

to dazzle on the grave of Poe adorned

The keystone of the poem is the line:

in the flood without all honour of some black mélange

which captures the corporeal macabre of Poe’s death. It can be read as mélange, the granite forming the grim tomb, but Mulrooney fills his poems with other references, and an unaccented melange is the fictional drug, the spice, from Dune. Maybe Mulrooney is referring to the theory that Poe was drugged. He was found at Ryan’s Fourth Ward Polls on the day of a local election. That area was notorious for cooping, a form of voter fraud in which unsuspecting victims were drugged and forced to vote at one polling place after another until being left for dead. Poe loved a tasty beverage, so it’s logical that he could have been slipped a Mickey Finn.

The penultimate poem after Mallarmé, ‘what silk’, is bewitching, a holey conjurer’s sleeve: a poem of missed opportunity, where time falls from the Chimera’s yawning jaws. A thoughtful recollection of “the cry of Glories he has snuffed”.

To sum up this collection of puzzle boxes: it’s slight in pages, but you’ll hold it with you. I could write so many more words praising it, from the sexuality of the final poem after Mallarmé – “the hair a soaring flame” – to the TV evangelism of ‘SLA’ and the chilling antiseptic detachment of ‘Endlösung’. You will get satisfaction.

Mulrooney isn’t afraid to delve into the tangled roots of English: you can feel him buzzing at the keyboard. His wahwahing voice is unconstricted. He will be missed.

What a thoughtful and precise review. I wish Mulrooney were here to read it. Your reference to Eliot is spot on.

We had just seen “Whistler’s Mother” or as it is titled “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1” at The Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, but Mulrooney loved all of Whistler. It is a delight to read this, really, thank you. Heather Lowe