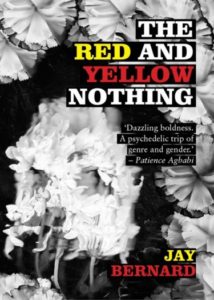

The Red and Yellow Nothing by Jay Bernard

– Reviewed by Fiona Moore –

The Red and Yellow Nothing is the story of a quest… or is it, and if so, for what? Jay Bernard has unearthed an Arthurian tale from a Middle Dutch poem of possible French origin, translated into English a century ago. Sir Agloval, a knight travelling in Moorish lands, meets a princess and then leaves her. She gives birth to Morien, who grows up and rides to Camelot in search of his father. He has some adventures, and there’s a happy ending… in the original.

In The Red and Yellow Nothing things go differently. I’ll talk about it in terms of the story, which is one way to give an idea of the variety in this unusual pamphlet. Adventures become experiments in time, space and identity, spinning out of a kaleidoscope of poem-episodes, leaving me dizzy and disoriented.

At first we seem to be following a conventional quest, updated with brio and irony. Morien “enters page left on his horse, Young ’Un”, to be serenaded in assured ballad-style by a bard:

Some things we know but can’t say why

the dark is what light travels by

a blind man’s finger is his eyyyyyyye

in the land before the story-o

Next, Morien makes a hell of a fuss because no-one will help him. I sense that he’s expressing the hurt of any abandoned son, plus the hurt and frustration of a stranger, “black from head to toe”, who people just want to get away from (poem II):

Everyone says

I know not good knight where your father dwells,

mincy mincy moo. Ergot brained fuckers. Fight me.

Everyday racism is just the start; in poem III, Morien happens upon a competition in a castle. He doesn’t win, and the prize is a kiss from a blacked-up woman (losers’ prize: kiss her arse, which is smelly, details provided) while the early sixteenth century Scottish poet William Dunbar recites his poem ‘Of Ane Blak-Moir’, a cruel and, to modern sensibilities, repellent love-parody. Then Morien spies a black woman in the crowd, who turns to leave:

Her shoulders like a proto-stradivarius

lost to the sea. Which sea, Morien couldn’t say.

A red and yellow one, a sudden one, sudden.

.. and vanishes. Hence the pamphlet’s title. This episode, part Monty Python, part medieval /16th century horror, part brief love lyric, raises questions about what’s real and what’s not, who anyone actually is, and the experience of blackness in a world that was racist before the concept existed.

Morien witnesses a horrific, nightmarish execution scene, and poem VI contains a strange dream:

I dreamt that I dreamt that I woke in the wilderness

wanted for something and walked in the wilderness

black was the light saw folks made of green

and the rain was falling backwards

Bernard’s formal versatility makes poems like this stand out. Not that they aren’t all worked on, with vividly fantastical descriptions and striking turns of phrase. Her skill won’t surprise anyone who read her first pamphlet, your sign is cuckoo, girl.

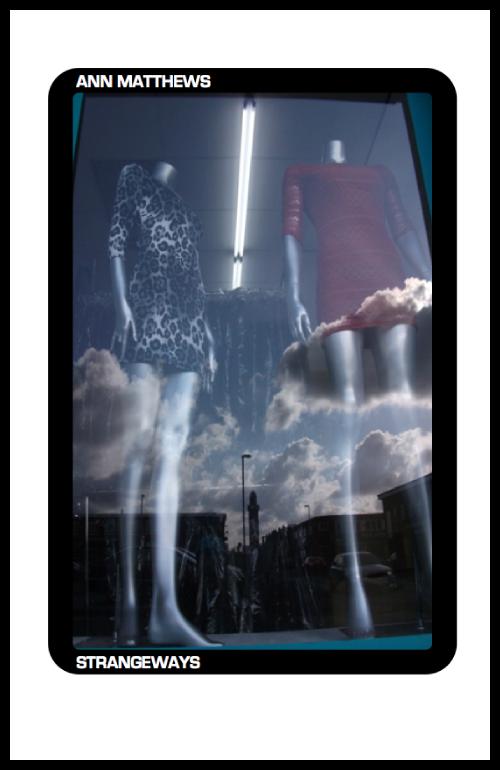

There are illustrations too, by the author, which perhaps work best with the more abstract parts of the narrative; for me they don’t enhance it, unlike Bernard’s useful notes and introductions to most of the poems.

The theme of blackness and light runs through everything and attracts interesting language, as in poem VIII, where African soldiers playing a firelit game talk about the strangeness of Scotland, “how different the flame is to air”, or poem VII, in which Darkness herself takes an interest in Morien:

Morien’s body speaks to

the thin high black he

sleeps in.

Later Morien finds a two-pound coin, crashes through time, becomes s/he and undergoes other transformations in a prose poem (XI) that’s part Hieronymus Bosch, part Salvador Dali, part modern gaming/dreaming fantasy. I had trouble linking this to the story, though it contains some inventive stuff:

Hadopelagic:

A roseate spoonbill snorts crushed ecstasy off the belly of a blow-up doll. Eats bunga kuda.

Sort of recovered but very confused, Morien continues his (his?) quest through “Earth pocked like natrolith and riven / with dried rivers” (XIII). He appears to succeed – he sights two knights, and the book ends with a quote from its source poem, in which Morien arrives at Camelot.

He was all black, even as I tell you:

his head, body and hand

was all black, save his teeth;

and weapon and shield, armour,

were even those of a moor,

and as black as a raven.

That coda returns us to the beginning: the familiarity of an Arthurian tale in which a stranger appears, and we know there will be adventure. But after all he’s experienced, who is Morien? What was his strange journey all about, and why should anything happen the way we think it might?

There’s some background on the pamphlet, and depictions of black medieval knights, here; the link is in Bernard’s credits. The Red and Yellow Nothing was joint winner of the 2014 Café Writers Pamphlet Commission, and is published by Ink Sweat & Tears.