Beckett by The Secret Experiment

Beckett

Developer: The Secret Experiment

Publisher: Kiss Publishing

Platform: Windows

-Reviewed by Jon Stone–

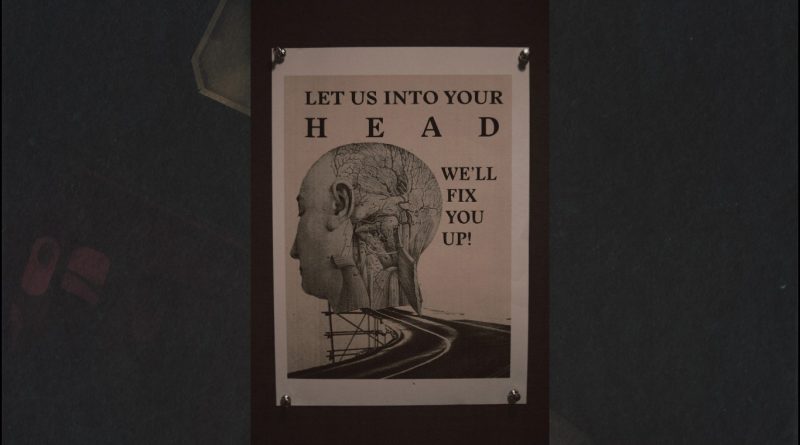

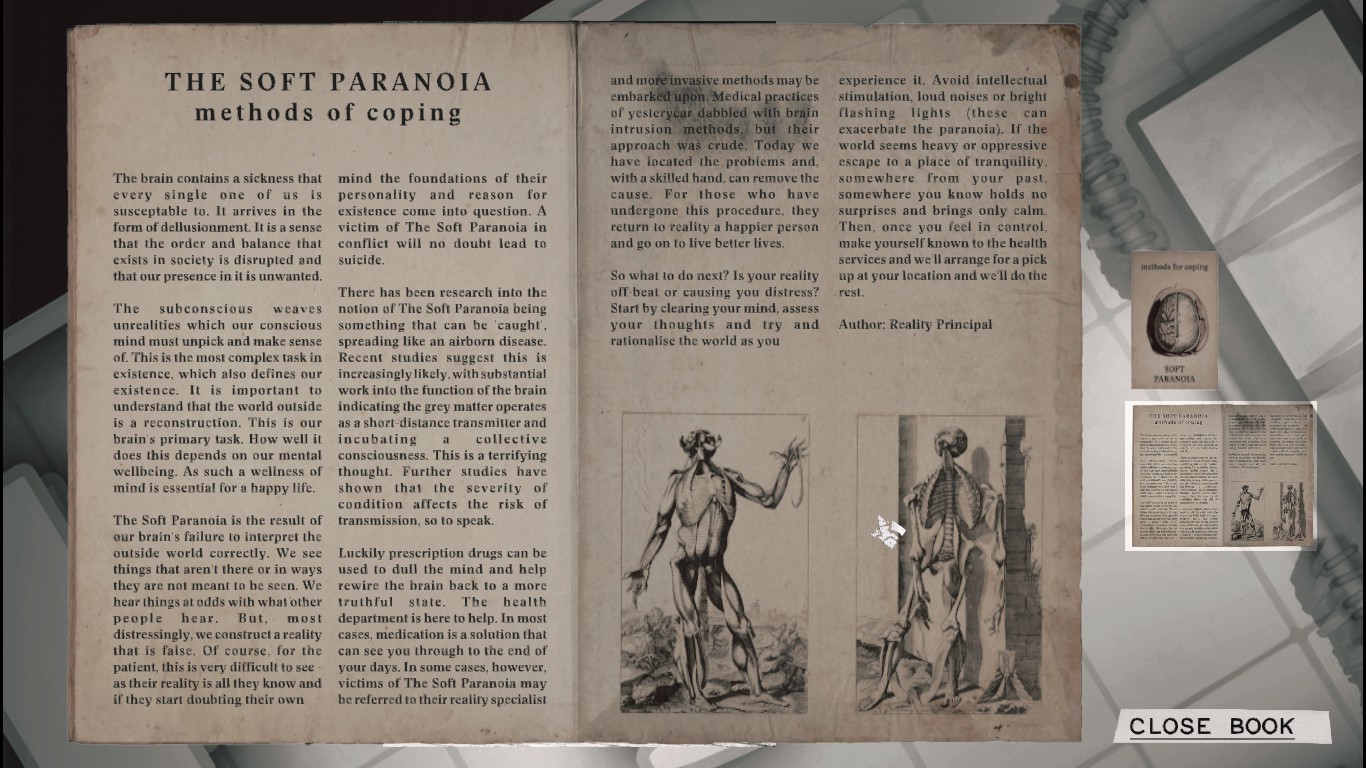

Beckett opens by calling itself a ‘literary work of fiction’, adding: “It’s a box. Open it. Question everything.” Avowedly, then, it sets out to explore and develop the hinterland between digital games and literature, and does so first and foremost by wearing its influences on its sleeve. Along with Beckett himself, the most obvious of these is probably William Burroughs – the persistent insect motif can’t help but recall Cronenberg’s film adaptation of Naked Lunch – but there are also shades of Philip K. Dick (in particular, A Scanner Darkly and Flow, My Tears, the Policeman Said) and Jean Cocteau. The visuals, meanwhile, are an impeccable homage to Dadaist art by way of Jan Švankmajer. The whole game is an unsettlingly animated interactive collage made from clippings, photographs, archive footage, posters, medical texts, x-rays and more, all boiled down to a murky, minimalist colour palette.

For maybe the first third of Beckett’s roughly three-hour play-time, this serves largely as a demonstration of just how well the surrealist aesthetic suits standard adventure game mechanics. It positions itself as a noir detective story, like LucasArts’ Grim Fandango and Westwood’s Blade Runner. As in those games, the player drives the plot forward by moving a down-on-his-luck protagonist (Beckett) toward various objects (or people) and interacting with them, unlocking the narrative piece by piece. Unlike those games, Beckett has little to no voice-acting; instead it makes use of copious text boxes for both dialogue and narrative description, in this way recalling another cult 90s title, Black Isle’s Planescape: Torment, with which it also shares a mild body horror theme. Beckett is far more stripped down than any of the aforementioned games though – progress is mostly linear, people are represented by symbols (a bottlecap, a typewriter, a toy soldier) and voices by cycling sound samples (coughing, scissor snips, jangling coins). There is little sense that one is actually solving a case or exploring a world so much as walking Beckett through the motions of gumshoe reconnaissance – mysterious callers, shady dives, sinister messengers, and so on. Still less is there evidence of the game’s avant-garde influences going deeper than its eerily effective, queasily shifting skin.

But as Beckett moves toward the centre of its mystery, its ambitions expand dramatically. It starts to play with the boundaries between genres and mediums in myriad imaginative ways, working in modernist sculpture, theatre and concrete poetry. It disrupts its own narrative with perspectival and chronological jumps, switches between two-dimensional and three-dimensional space, and extends the symbolic reach of its game-world so as to thoroughly blur the line between expressionism and interactive simulation. This retroactively improves the opening hour, as it becomes ever more apparent that the game up to this point has not been merely a system for representing literal narrative, but a refraction of its protagonist’s damaged psyche. While computer games have previously dabbled in rendering the human mind as play-space (DoubleFine’s Psychonauts being the most extensive foray), the results are usually didactic or cartoonish, the encounters explicitly real or imaginary. Here, the join between reality and subjective experience is deliberately difficult to make out, and this sits particularly well with the way text is animated: fragments flare up and dissolve into white, or trail after-images, or may be seen only partially through tears, or flicker on and off like faulty strip lights. If visual poetry is ‘the word made flesh’, to borrow Willard Bohn’s Biblical metaphor, then this is flesh that creeps and crawls, and reacts to the reader’s meddling.

There are lingering issues though, largely to do with the narrative framework. Its noir stylings are laboured – Beckett spends a lot of time recalling his doomed wife and mother, and they, like most of the other characters, are little more than cyphers. As if to drive the point home, two of the female characters are represented by, respectively, a pair of lips at the top of a pair of legs and a blow-up sex doll. Since the story is set in Borough, there are also rather dubious sketches of homeless people and building site labourers. The fact that the story comes filtered through Beckett’s broken mind is an unconvincing excuse, especially since the game otherwise takes care to accentuate unnerving details over broad stereotypes.

Additionally, where the writing leans away from open-ended fragments and towards straightforward description, it sometimes falls into the trap of over-explaining – so when Beckett finds a well-thumbed Mills & Boon title while searching his client’s bedroom, the game hits you over the head with: “Daisy is lonely. She craves another life, an escape from the waking world.” There are also a couple of points where the procedural logic is unintuitive; for example, I wasn’t able to go down a flight of stairs until I had spoken for a second time to the client so that she could tell me her son’s room was downstairs.

Finally, on the negatives, those occasions where the game required me to demonstrate some sort of recall or game-sense were so few and far between that they seemed tacked on. There are multiple endings but getting a different one seems to be a case of going back to particular points in the narrative and doing something ‘right’, which runs counter to the game’s otherwise impressive commitment to ambiguity.

Despite its flaws, though, Beckett is a beautifully put together piece of work which pioneers new methods of mingling interactivity with narrativity and poetry. Even if the plot doesn’t grab you, it’s worth playing just to see the ways in which The Secret Experiment have mutated the written word into something that writhes under your touch, and to sense the excitement of what this entails for the future of literary-game hybrids.