Sad Press Pamphlets by Daisy Lafarge, Emilia Weber & Eley Williams

Daisy Lafarge, understudies for air

Emilia Weber, FAMILIARS

Eley Williams, Frit

– Reviewed by Becky Varley–Winter –

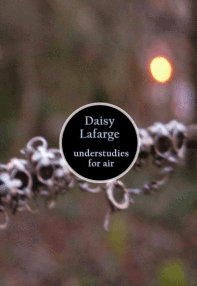

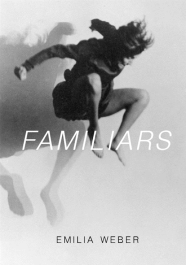

In these three pamphlets from Sad Press, poetry arrives in its own light: there are no external blurbs or preamble about the poets, though the cover art indicates each pamphlet’s mood. Daisy Lafarge’s understudies for air opens with a rope of interlinked chains circling a tree branch, Emilia Weber’s Familiars opens on a figure mid-jump, and Eley Williams’ Frit features a frizzling comet.

Daisy Lafarge introduces understudies for air through a quotation from Anaximenes: ‘The source of all things is air’. Anaximenes speculated that the entire cosmos was made of air, and that the ignited breath of earth formed the stars. Lafarge uses this to prompt a sequence of poems on air. The fact that she begins with ‘childhood air’, then ‘sibling rivalry air’ suggests that the sequence might weave chronologically into the course of a life: however, as ‘childhood air’ comments, it is ‘difficult to pin the beginning / of the bad air’.

Lafarge begins by addressing a ‘you’ who is obscurely troubled, as if the poems are written by a psychotherapist to a patient: ‘an imaginary phone call / to your imaginary sister prompts / another suspicion of the bad air’, she writes in ‘sibling rivalry air’. Air immediately invites the idea of atmosphere, which this poem creates through a panorama ‘varicose with rain’, the imaginary sister seen like ‘a fly, honeyed in amber’ on the far side of a lake, perfectly conjuring a figure inside a lit-up window in the dark. The therapist asks

[…] why you always place yourself outside of the house,

vision thick with the black rain,

and never inside it, alongside her

The fact that the sister in this poem is ‘imaginary’ only intensifies its loneliness. Lafarge’s poems meditate on damage as a damp air, that’s hard to get out of or off your chest: ‘at birth, you grew maladaptive / breathing patterns to survive / the air’, she writes in ‘desecration air’.

In ‘sapling air’, she switches to an anxious first-person ‘I’ who is sure ‘there’s something wrong with the air‘. At this point, I begin to think about this sequence’s possible connections to environmental destruction, a literal ‘bad air’. However, Lafarge speculates on various kinds of poison. In ‘constitution air’, fascist graffiti becomes an airborne virus, breathed in and spat out. Lafarge’s airs are full of suppressed surreal chills, and her subtly flawless sense of rhythm and rhyme make the poems work on a subterranean level: they remind me of the old, mistaken theory that illnesses were caused by miasmas emerging from the earth. Their anxiety often culminates in a queasy, unsettled beauty. In ‘false alarm air’, an elderly lady emerges from a high-rise building, wrapped in a towel, ‘each of her limbs a sprig of pale lavender’, steaming vividly into the mind’s eye.

The title of Emilia Weber’s Familiars suggests witches’ familiars, and this pamphlet does often refer to animals and intimacy. It opens with a love poem to an ‘Echo in the shape of a wolf’:

bring me wasps in your mouth

drop them, call them

‘breakfast’

Self and other become mingled, taking turns to play wolf. The poem ends in an intentional grammatical fragment. Its details are striking, although they pointedly don’t resolve themselves into conclusion: in this pamphlet, the parts are more animated than the whole. If Weber’s poems are really ‘familiars’ or intimates, this may explain why they speak in a private voice, as though addressing somebody already-known, out of frame. The second poem is called ‘Hey Melchior’:

Too bad your feet trespassed against me

giving birth to this sorrel child, from our

Hammersmith flyover all the way to Dover

Melchior is one of the Three Wise Men in the Bible, so this speaker might be playing Mary, giving birth to Jesus (the ‘sorrel child’). Then again, maybe not – the poem is an assemblage of ‘linguistic dead ends’, and I might be getting it all wrong. Why does Weber refer to the Chartists here, and to the soviet space mission? Familiars is full of ‘dazed tangent’s, to the extent that I don’t know whether I am meant to connect everything to everything else, or whether it uses a collage-like method, in which disjunction is the intent. However, her work has something of Mina Loy’s complex physicality (‘I spun semi solid / bitumen / lathered it / onto the arc’, she writes), and poems like ‘Chorus’ and ‘Malin Head’ do sing, holding notes of tenderness and rebellion. The cover image features Gret Palucca, a German dancer known for her energetic jumps and ‘merry confusion‘: this might also indicate how to approach Weber’s poems.

Eley Williams’ Frit takes its title from a triple-meaning. Frit can mean ‘a calcined mixture of sand’ ready to use in glass-making, or a ‘vitreous composition from which soft porcelain is made’. It can also mean ‘frightened’. Williams is best known for her short story collection, Attrib., which showed her preoccupation with the intricacies of language. The poems here contain a similar fascination with the exact meanings of words, as well as inventing new ones, such as ‘wrenbig’ and ‘pithlight’. Williams always seems in search of exactly the right word for a feeling. The poem ‘Witzelsucht’ – meaning an addiction to puns – rattles through energetic wordplay and slippages in meaning, between ‘pawed’ and ‘pawned’, ‘calqued’ and ‘caulked’, like a cat playing whack-a-mole.

The next poem, ‘Clementines in November’, opens with ‘Sudden gladness as sweet hullabaloo of understanding’. I don’t think I’ve ever seen ‘hullabaloo’ so sweetly used. Words keep buzzing and zinging, communicating a heart in the throes of language. ‘Clementines in November’ is a love poem, with something like Frank O’Hara’s joyousness, but it has a fizzier edge, riffing all over the place. The line ‘the awful necessity of drinking raucous coffee’ sounds like a tongue-twister, and captures an enjoyment in writing which becomes contagious.

In ‘Mislist’, Williams runs into one long sentence:

[…] I have started using words like

suddenly and seriously to get the idea across to you as quickly as possible and they

will still be faster still in italics suddenly seriously as if time is of the essence and I might

do anything, honestly, I could be very dangerous, might add olive oil to ice cream

even and become that kind of person and I hope you sense here my delight

In these idiosyncratic, funny poems, Williams’ command of words is such that she seems able to do almost anything she likes. ‘This week I find that you are particularly interested in moss’, she writes, ‘so I am getting into moss’. And why not? Why not moss?