Are We Where We Are #7/8, (Stephanie Ridings and Cristina Catalina, Shop Front Theatre, Coventry, 11 October 2018)

review by Stella Backhouse

According to a recent survey by pollsters ORB International, “people are disgruntled with the protracted Brexit process overall: 52% of those asked want those responsible just ‘to get on with it’”. Speaking for myself, I totally get that. While politicians continue to agonise and bicker over what Brexit ‘means’, I’ve given up reading speculation that imparts nothing concrete. It wasn’t what I voted for; but with less than six months until we leave, I’ve accepted that one way or another, it’s going to happen. For now, I’ve decided to wait and see what Brexit actually is.

Although neither was specifically about Brexit, numbers seven and eight in Shop Front Theatre Coventry’s Are We Where We Are series were, in some ways, reflective of this dichotomy. Cristina Catalina’s The Things We Tell Ourselves was a search for solidity in a confusing, post-modern world where “truth is what we want it to be”. In Don’t Cry For Me meanwhile, Stephanie Ridings told the story of how her family came to terms with an all-too solid reality that was not the one they would have chosen.

Of all the many and varied pieces of theatre premiered so far as part of Are We Where We Are, Cristina Catalina’s monologue was the one that addressed the central provocation – are we where we are? Or are we in a false position? – most directly. Catalina unflinchingly unpacked the question by breaking it down into smaller questions like who are we, where are we, and what is false?

Answering the last question, she concluded that “everything is false if we let it feel that way” and that our ‘truths’ should really be seen as manifestations of the things we want to be true.

We’re subject to the narratives we choose or are forced to believe

We are where we are because that’s where we need to be, to be OK

The dilemmas posed by the near-impossibility of unmediated gaze crystallise around her relationship with her small son, and his constant questioning. “Mama, what’s that?” he asks. “How to interpret what he sees” ponders Catalina “without telling him what to think?”

In some ways Stephanie Ridings approaches this situation from the other direction. She and her family know exactly what their problem is; they can conceptualise and even name it. Their difficulty is in accommodating themselves to the reality of the family not being “what we thought it was”.

Endearingly wrapped around the Rice/Lloyd Webber hit “Don’t Cry For Me, Argentina” from the musical Evita, Ridings told the story of her older brother, whose early precocity meant that he could sing the song from start to finish without prompts at two years old. His proud parents were encouraged to believe they had raised a genius.

Things began to go wrong after he completed his Masters. Out of the blue, he attempted suicide. After that, he moved back in with his parents – and there he stayed. For years. He resisted all attempts to get him to re-build his life. Eventually, he was diagnosed with high-functioning autism.

Ridings’ father struggles to understand what had happened. His own life story has not equipped him with the skills to deal with a son who “isn’t being what a son should be”. His tendency to cope with it by erupting into “a masterclass in shit-losing” means Ridings’ mother is constantly on edge. Ridings herself delves deeper and deeper into what the diagnosis might mean but gets nowhere. Her brother wasn’t a genius after all; when he sang “Don’t Cry For Me, Argentina”, it was just mimicry – but what did that mean? He’d been pretending his whole life, but what did that mean? So many questions. So few answers.

In the end, a kind of equilibrium is reached. The family “grieved the man he was and won’t ever be and accepted the teenage boy that he seems to have turned into” because “being happy needs to be enough”.

And Cristina Catalina, despite all her anxieties, finally seems to concur with this view: our never-ending hair-splitting, prevarication, and search for the Nirvana of absolute meaning exhausts us and excludes us from the serenity that comes from simply being. Her parting image is of her son, playing in the snow while all around him “minute little flecks, thrown about in the wind, become almost invisible”.

Whether this approach can work when almost half the population of a major nation wakes up one morning to the news that our country is “not what we thought it was” is perhaps more open to conjecture. But maybe the words Ridings’ brother told his parents at two years old can offer wisdom to all sides in the still-unresolved Brexit saga: “It won’t be easy. You’ll think it strange…”

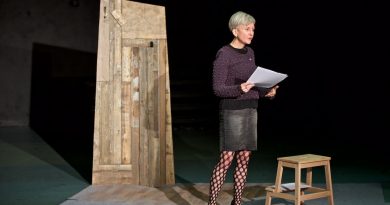

Image of Stephanie Ridings by Andrew Moore