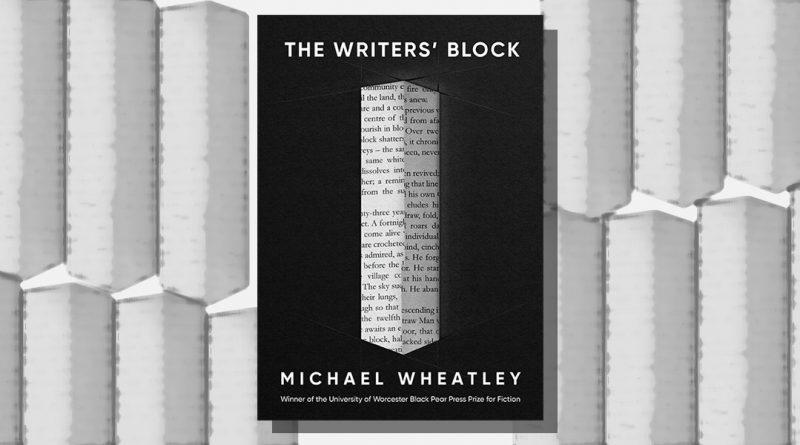

The Writers’ Block by Michael Wheatley

-Reviewed by Joshua Lambert-

In his debut collection, The Writers’ Block (Black Pear Press), Michael Wheatley gives us a biopsy of literature. This is writing, a book about books. It’s a fairly scant collection, comprising four short stories and a piece of flash fiction, but in a confined space Wheatley has managed to create an intelligent, moody exhibition of writing anxieties.

‘The Straw Man‘

Denizens of a twenty-three story tower create magnificent works of art, celebrated each year. The current artist in residence, the Straw Man, makes effigies and offers them to the furnace.

The prose here, as everywhere else in the collection, is pleasingly mechanical, economical, and precise. Words fit flush against one another; sentences slide together locked and oiled.

“The furnace still roars damnation. The effigies splinter, dismantle, divide into two; individual strands of straw, then nothing. Withdraw, fold, wrap; cut, bind, cinch; pierce and burn.”

In this story especially, the style also dips into the abstract, creating a textured reading experience that is at once precise and fluid, building an almost menacing mood. The story embraces the abstract too, as the Straw Man starts to build a final effigy from the splinters of his own body. It is a hypnotic process to read, though not an overly affecting one, reading as a trite, ‘sit at my typewriter and bleed’, metaphor. Nonetheless, ‘The Straw Man’ sets a smoky atmosphere that sustains the collection moving forwards.

‘Simulacrum‘

Wallace, an expert on the anonymously published novel ‘Simulacrum’, meets a man claiming to be its two-hundred-year-old author. The story as a whole is an intelligent, narrative interrogation of Roland Barthes’ ‘Death of the Author’. This academicism and literary engagement is incredibly well-realised and written. Anyone who’s studied or taken a keen interest in literature and literary theory will find a lot to enjoy here.

“From afar, Wallace thought he appeared almost in image like Berche, the Shylockian or Faganesque figure from Simulacrum to whom Dickens was undoubtedly indebted.”

The prose, however, is overly academic. Clinical. The writing is strangely detached and, being disinterested in its own narrative, fails to capture interest. In one instance, Wallace is walking down a street and notices an occult shop. There’s a lengthy description of the shop, followed by the statement that it was ‘of no particular interest to him’. It’s an oddly sterile passage with little practical purpose, and is indicative of the collection’s pervading reluctance to engage with a story’s content beyond its allegorical value.

‘A Burial at Sea‘

Less a story and more an extended visual metaphor: a woman is drowning, crushed within a sea of books, fighting to free herself: “Spines cut into her ribs. Covers dug into her arms. Pages pressed down on her shoulders.” The canon she is buried under happens to be almost exclusively white and entirely male. “Whitehead. Conrad. Nabokov. Ibsen. Brecht. Faulkner. Dostoevsky. Joyce.” This listing goes on for quite some time, and it’s hard to tell whether canonical sexism is being protested or propagated here. Though elsewhere the simplicity of Wheatley’s metaphors are a winning feature – the Straw Man is a rhetorical straw man; ‘Simulacrum’ is a simulacrum for literature – here it is too rudimentary to inspire analysis. Is it about the pressures of writing under the weight of literary forebears? The monotony of canon? The impossibility of experiencing or understanding such a cacophony of fiction? Though written well on a prose-level, as an allegory the piece is uninspiring; as a story it’s anaemic. Nonetheless, it’s worth reading if only for its killer last line.

‘Catharsis‘

Half flash fiction, half prose poem, this bite-sized piece continues the theme of writing about writing, focusing on the emotive side of a workshop. The intensity, however, reads as overdramatic rather than intimate. For a piece about emotions it needs much more personal engagement. Ultimately, it gets lost in the collection.

‘The Writers’ Block‘

In the titular story, we see a piece of short fiction go through various drafts, ruminating on the nature of literature and writing itself.

A writer, named Michael (like the actual author), works in the Writer’s Block, a tenement housing a menagerie of writers moving up and down floors with each success and flop. Details change with each draft, boiling over with self-loathing. At its heart, this story is an excellent, highly successful study on self-doubt, as the author beats his head against a wall of failure and disappointment.

The deconstructed, typographical play of the middle drafts is the height of the collection, and I suspect is much more indicative of Wheatley’s talents than the collection’s weaknesses. I do think it could have been pruned, and the story would be better without its turn to hope towards the end, mixed with an oddly didactic take on publishing (somewhat naïve for a debut collection). Nonetheless, this story shows Wheatley’s competence at its best.

Conclusion

As a whole, The Writers’ Block may leave readers at odds with themselves. These stories demand to be analysed, and beg the reader to provide the key to each metaphor and allegory. The problem is, Wheatley doesn’t manage to give the reader much reason to do so. The collection is highly intelligent and well-written, but it’s not overly engaging or enjoyable. Not unengaging, not unenjoyable: just middling. This experimental self-insertion and exploration of literature has been done much more successfully in any number of texts before – The Raw Shark Texts, Albert Angelo, House of Leaves, Labyrinths, to name a few. The interrogation of these ideas shown here is more a repetition than a development. Even so, the collection marks Wheatley as a talent to follow with an acute sense of literary and writing anxieties, especially when his intelligent ideas are mixed with intimacy and vulnerability.

Find out more about The Writers’ Block on the Black Pear Press website.

Reviewed by Joshua Lambert — Josh graduated with a degree in English Literature with Creative Writing from Bath Spa University, and has spent his time since then as an editor working with independent authors and self-publishing houses. He’s a ravenous consumer of most anything: literature, food, film, games, and graphic novels, and is equally zealous about deconstructing those things. Thus, reviews, and long, one-sided conversations.