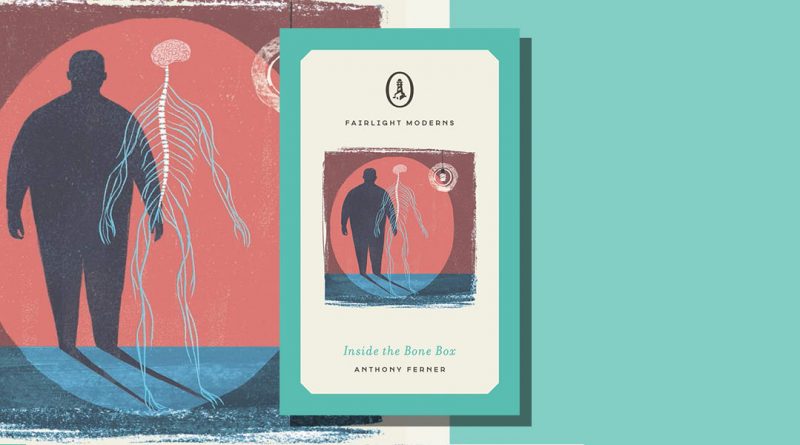

Inside the Bone Box by Anthony Ferner

– Reviewed by Cath Barton –

The portrait that Anthony Ferner paints in this Fairlight Moderns novella, of Nicholas Anderton, a successful neurosurgeon, is like a painting in which a skilful artist has used colours you had never before realised existed in skin tones to convey a man’s complexity and depth. Ferner has clearly researched his subject thoroughly, and to convincing effect. He spares the reader none of the visceral details of brain surgery: as in other arenas of life that simultaneously repel and attract, we may feel squeamish about the contortions of the hidden and essential soft tissue inside our skulls and yet find ourselves horribly fascinated. No wonder. This is, after all, the location of all we are as sentient beings, and the precise and detailed descriptions of Anderton’s work are in large measure what make Inside the Bone Box a compelling read.

Anderton operates in a sphere where the smallest miscalculation can have fatal consequences, and even the most skilled make mistakes.

This is encapsulated in the first chapter of the book, Captain America, which could well stand alone as a short story: Anderton, attending a conference in a chi-chi Basque resort, witnesses a tragedy as a kite-surfer is blown by a sudden and violent squall into the plate glass windows of the conference centre.

He is dressed in a superhero outfit, causing Anderton to reflect:

“Afterwards, what stayed with him was the look on the young man’s face: an expression of astonishment that such a fate could be visited on Captain America, that it had come to this.”

The surfer had made a miscalculation and the consequences were fatal. So it is when a mistake is made in neurosurgery, and that is the subject of the morning’s discussions in the conference. Anderton has been musing on one of the so called ‘never events’ in his own career, in which his junior had inserted a nastrogastric tube incorrectly and it had gone into the brain and drawn out cerebral tissue ‘like a soft white curd.’

It is no wonder that Anderton seeks refuge from the memory of such horrors. Furthermore his marriage is unhappy. His escape is through food, in gargantuan style: at the Italian restaurant round the corner from the hospital where he works the proprietor is a kindred spirit, offering an offal-based menu of excess which culminates in a dessert made with pig’s blood.

Anderton’s life has been based on appetites. His marriage was originally more about lust than love, something which, when he encountered it subsequently and unexpectedly with a patient, he experienced as ‘painful pleasures’ that made him ‘deeply unhappy and afraid.’ The joys of sex and eating are, for him, more straightforward.

Ferner’s depictions of Anderton’s eating and the specific effects of his weight gain on his body are as vivid as the details of the delicate surgery which he conducts. Anderson is almost a Dickensian character, and his wife Alyson, making her own escape from the sterility of her marriage through drink, is insubstantial in comparison; although she does have her own unexpected burst of rebellion, it is Anderton who commands the stage. Others – his colleagues, children, patients – serve only to support the portrayal of this literally larger-than-life character.

It is Anderton’s work that makes him feel alive and, for all the accumulation of errors while operating, embarrassments with women, an overheard jibe from a junior about mating elephant seals, the health risks and his wife’s scorn, he cannot imagine how things would be without it:

“It would be a sort of half-life, a twilight zone; without surgery, what would he have left to embrace, except his fatness?”

But as his weight balloons, a crisis is inevitable, and when it comes he has to accept what he has so far rejected: surgical intervention, submitting himself to the risks of anaesthesia and the scalpel. Alyson too takes action to address her drinking, but whether their relationship can be restored remains an unknown.

The more urgent question for Anderton is what will happen when, as a less-fat man with a sadly-faded sense of smell, he returns to work. The author leaves this open too, but to answer it would require a longer book. The satisfactions of this novella are in the portrayal of the complex character of Anderton and of the work which he conducts ‘so close to the fearsomely fragile stuff of mind’ inside the bone box of the brain.

Find out more about Inside the Bone Box on the Fairlight Books website.

Reviewed by Cath Barton — Cath Barton’s prize-winning novella The Plankton Collector (2018) is published by New Welsh Rarebyte and her second novella, In the Sweep of the Bay (2020), by Louise Walter Books. Cath is also active in the on-line flash fiction community.

Photo © Toril Brancher

Twitter: @CathBarton1 | Website: cathbarton.com