‘flick invicta’ by Sarah Crewe

-Reviewed by Charles Whalley–

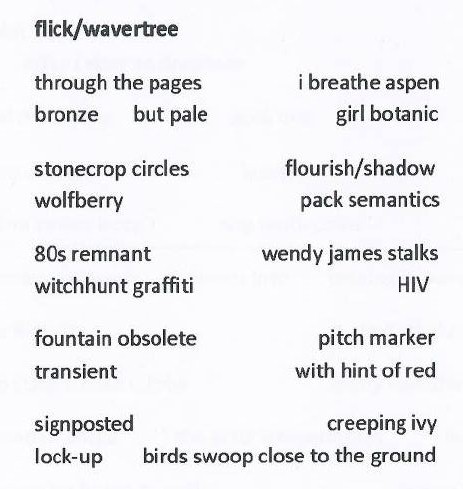

flick invicta is a reminder that all poems are lists of words to be interpreted. Few of Sarah Crewe’s poems contain complete sentences; most toy with some connective syntax; some are almost entirely nouns. The poems are often formatted with large spaces within the lines, justified with both margins, accentuating the syntactic gaps. The first poem, ‘flick/wavertree’, runs:

The formatting creates two columns, encouraging the eye to move up and down as well as left to right. Likewise, the isolated words and phrases encourage interlocking connections in multiple directions, like the lines drawn through the letters of a wordsearch puzzle or like (to borrow from Wolfgang Iser) the constellations drawn by connecting stars. We have, for instance in ‘flick/wavertree’, the string of association of “aspen…girl botanic…stonecrop…wolfberry…creeping ivy”. In this sequence “girl botanic” links with “witchhunt” and then “stone[…] circles”. The “wolf” also connects with “pack” and perhaps “stalks” (as what I imagine packs of wolves to do), whilst “stalks” taken as a noun rather than verb connects back with the plants. As well as the sound patterns (most plainly in “graffiti…HIV”), these are exercises in (pack) semantics, as each word’s connotations reaches for another. It requires a reading that is reticular rather than linear; the poems develop like dot-to-dots or Spirographs.

*

Many of the poems reference places in Liverpool, such as Wavertree and Newsham Park, or, in the case of ‘Mil-Mi ‘85’, a film set in, and specifically about, the city. These locales as a setting for a poem circumscribe the disconnected phrases of the poems into atmosphere, as in ‘flick/newsham park’:

‘dips her feet in mallow fork tailed birds swoop grade II rooftops circumflex

pyramids on stilts flick smirks jack in mind phantom boy penchant for angles’

Fixed geographically, the nouns eschew associating syntax; their common thread is their shared cinematic invocation of place.

Liverpool also serves as one side of a binary opposition, expressed in ‘iris on the wing’ as “north west/south east”, with Liverpool as the “not london” of ‘elephant’. This sense of speech from a position (geographically or not) of otherness or cultural alterity recurs throughout the pamphlet. In ‘Mil-Mi ’85’ the speaker remarks: “the actor’s accent slips……….mine never does”. The word “accent” implies a deviation from a ‘norm’, and one must “slip” from an “accent” to prove that it is indeed an “accent” and not one’s only way of speaking. To have an accent that “never” slips is either to be one entirely committed to performance, or to be one whose ‘real’ self has been relegated as such.

*

‘flick/blue heaven’ includes the line:

‘flag on the brow side’

I am completely at a loss to articulate why I like it so much.

*

The isolated nouns of flick invicta lead the reader to think about how the process of fashion (as manufactured obsolescence) imbues objects with an embedded, complex datedness: to be impoverished is to be condemned to the past. The neglected landscape of flick/invicta – the “creeping ivy/lock-up”, “doc leaves, “wasteland/sidelines, “wasteland nursery/flaky social club”–mirrors the “80s remnant” interest in old clothes: “dog tooth coats”; “art deco[…]flapper chic”; “1950’s polkadot”. But these clothes are not just haphazard gallimaufries of fashion’s merry jetsam fashion; these are sophisticated performances of the present’s versions of the past: it is flapper chic, where fashion reasserts its ownership over what it left behind. Considering the disenfranchised position of the past and its symbols, there is something troublesome about this appropriation or glorification of disempowerment, as Crew suggests in ‘elle d’en’:

‘O you look so pretty in

housewife chic you wear it well

recession in petticoat’

There is the fear, in the word “housewife”, that the social and political realities of the past may be resurrected within the fashions, that retro is a hidden conservatism.

*

*

The character “flick”, who appears throughout the pamphlet, is essentially performative, with a verb as a name since she must do to be. Often through her, flick/invicta explores the external signs of femininity, of the ‘masquerade’ (in Mary Ann Doane’s term) of “red dress peroxide”(Mil-Mi ’85), and how, as with elsewhere, one can become empowered from a disempowered position, how one can live earnestly through signs that have been degraded as fake.

The final, overarching binary opposition running through the poems, after South West/North East or Present/Past, is gender, in terms made clear by the reference in ‘flick/newsham park’ to a nursery rhyme: “two for joy[…]/[…]three for a girl”. The nursery rhyme implies a greater value of men not only in that they are worth an additional magpie, but with the logic implied in the patterning of the first rhyme: ‘girl’ is to ‘boy’ as ‘sorrow’ is to ‘joy’. The same poem also names the three imprisoned members of Pussy Riot, who emblemise one form that empowerment and subversion can take as well as the risks of attempting it: “flick thinks of maria ekaterina nadezhda”(‘flick/newsham park’). (Sarah Crewe was one of the editors of Catechism: Poems for Pussy Riot, the tremendous anthology which deservedly won the Saboteur Award for Best Poetry Anthology this year.) A similar model of female power is found in Cheetara, the “cunt cat hybrid” who “asphyxiate[s] prey”(‘hail cheetara (forever becoming)’), but mostly in “flick”, who is always the centre of her poems, always moving through the settings, and who often only has a verb following her name (e.g., “flick smirks”, “flick invokes”). Flick is the source of agency whenever she appears, as the one who ends the poem ‘flick/peacock’ with “let’s walk”, refusing the passivity normally assigned to the female. She is the only confident agent at home within the depthless, illogical atmospheres.

*

Sarah Crewe’s poems are deliberately resistant. flick/invicta raises the question: does a poetry which comes from outside, or which challenges, dominant ideology also need to come outside of normal syntax, to exceed normal registers? Does poetry need to challenge our modes of interpretation before it challenges anything else? Some of the poems in the pamphlet become so obfuscated as to resemble catalogues of private obsessions, and seem like the “secret code” mentioned in ‘bridge’. Others are, in context, remarkably conventional. But the best are hair-raising and subversive, breaking language up to “bring the vowels back” and “prise consonants/apart”.

Pingback: ‘flick invicta’ by Sarah Crewe | THE OTHER ROOM

Pingback: ‘flick invicta’ by Sarah Crewe | THE OTHER ROOM

Reblogged this on Paul Hawkins.