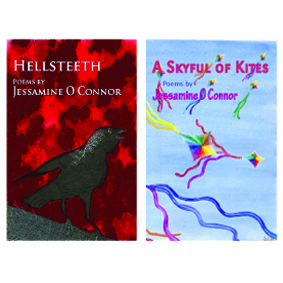

Hellsteeth by Jessamine O’Connor

-Reviewed by Afric McGlinchey–

Jessamine O’Connor is a relatively recent name to appear in the Irish poetry world, and after winning and being shortlisted in a number of competitions, she’s one to watch. The repertoire in her début chapbook, Hellsteeth is often physical, the poems populated by the elderly, the newborn, and everyone in between, as well as herself. By far the strongest poems for me in this chapbook were the well-placed first and last ones. In the opening poem, ‘Crows feet’, ‘Crow lands / on the blade/ of my shoulder, // Clambers in brambles,/cocks her beak, it’s time’. The pleasing metaphor and the bonding hinted at in ‘our’ almost act as an endorphin: ‘there is all / of our life / for her // to pace / and claw / my bread white skin’. I wish there had been more of this in the chapbook, but the energy displayed here, the wry tone, surfaces elsewhere, too.

Like Sharon Olds, she is not afraid to use the intimate details of her personal life in her poetry. These poems describe simple scenes that turn out not be so simple, a moment sliced open to hint at musculature and skeleton. There’s the ‘alien…spooky’ foetus who turns her bony back on them in an ultrasound scan and ‘I recognise instantly the child of my lover.’ Perhaps it’s the same lover who has onion-breath ‘so strong/ It would knock me down// If I wasn’t already/ On my back’.

You find yourself both wincing and grinning at the comparisons of the three fathers to her labours and the births of her three children in ‘Three new fathers’: the awkward, gotta-get-going first father, the absent, threatening second father, the ‘do as you’re told’ third father who endures her crushing his hand before ‘I roar, and push her out, / Just like that.’ The poems are instantly accessible, so you’d be tempted to read swiftly. But it’s the unsaid that allows mystery to be retained.

In ‘Regular’ the colloquialism of the writing style is appealing: ‘That’s the silver spoon in her mouth / has her talking like that…’ This would be an inconsequential poem if it weren’t for the slight shock of revelation in the final lines that redeems it: ‘Later, ntangling her hair from his hand / He wondered if he’d gone too far.’ This is O’Connor’s strength: the small frisson, the chill that accompanies each personal encounter in these poems.

She also shares something of Rita Ann Higgins’ feisty independence of spirit and clarity. Anything at all might come within her poetic orbit, including ‘Asimo – on Prime Time TV’ which describes a four-foot-three robot: ‘Of course they say you’ll do the jobs we don’t want./ As if a million-dollar-man like you will ever be wasted cleaning loos,/ Or down an aluminum mine,// Or picking over smouldering plastic/ to find pieces of re-useable metal/ Like our children do.’ It’s her politically vehement tone, more than anything else, that identifies O’Connor’s voice.

There’s the sense that she is immersed in the quivering moment of flux, latching on to a brief reflection, as in ‘To Samar Hassan’ after reading about the death of photographer Chris Hondros, who took the iconic photograph of the Iraqi child in a ‘spotlight of grief’ seconds after her parents had been shot in front of her. After seeing the girl’s image in the paper again, O’Connor needs to hold her own baby, ‘weigh that bulk in my arms, and squash/ my dry face against her clammy cheeks’. It’s always a challenge to attempt to write about someone else’s personal grief. Wisely, all O’Connor does is acknowledge what she can express, simply: ‘I see you, and hear that thing people say / How you don’t know what you’ve got ’til it’s gone’. It’s a trite cliché, the kind you hear in song lyrics, but she’s holding her own baby in her arms, and well, clichés become clichés for a reason. While the language is prosaic at times, and the content rather straightforward, it is also unaffected.

There’s a refreshing edge to the anecdotes she narrates, which ensures that she doesn’t slip into sentimentalism or self-pity. In ‘We’ve come to see her’ (a title that is oddly unimaginative), she describes a family visit to a hostile great aunt who’s in a care home:

‘The elderly eyeballs have spun

Round, clear and hard,

She’s going to swipe.

The tallest child looms awkwardly,

His sister teeters with pinking eyes,

The box of chocolates going off in her hands.’

What kept me reading was an undeniably voyeuristic curiosity about her revelations. Though there is a sense that these are confessional poems, like a strip tease, they show us enough but not too much. In ‘Fracture’

‘Close your eyes and lie back,

Shut your mouth,

Relax, just picture the money…

…until slowly we’ve coldly unclothed our skin,

Looked away,

And let them in.’

There’s a cold pragmatism here, that nonetheless evokes the hurt and bitterness of being coerced into this situation. I spotted a flash of resemblance between the speaker and the grand-aunt who’s been forced into a care home. This is a poet whose honesty is sometimes raw: When ‘he’ offers sympathy: ‘I snot on his shoulder, and my eyes drain pride/ Down the blue of his waterproof jacket’ (‘Surprise’)

The undeniable earthiness of her work is evident again in ‘Invisible art’ which describes an exhibition of empty canvasses, the audience reading the labels and nodding, while ‘a streaker/ jiggles barefoot/ through the crowd./ No one looks/ at his bouncing balls,/ his conductor’s hands,/ his Rubenesque flesh…’ But O’Connor makes the reader look. Not just fleetingly. In detail.

Yeats once said, ‘I am still of the opinion that only two topics can be of the least interest to a serious and studious mood: sex and the dead.’ In her final poem, ‘Hellsteeth’, (my other favourite), O’Connor’s evocation of her lover is in his physicality, not in the bedroom, but in chores: ‘he was springtime/ Up on rotten ladders’. Now, ‘He isn’t belly-deep in rushes/ Or chasing pigs…No one there/ Since he’s been gone/ Every day of the last ten years.’ It’s the vividness of the imagery and especially the impact of the last line, that makes this portrait, and this poem, so poignant.

While the chapbook is uneven in terms of quality (and editing), you sense that this is a poet who is going to develop. In her strongest poems, Jessamine O’Connor makes the reader stop and think. Read again.

Reblogged this on Fox Chase Review.