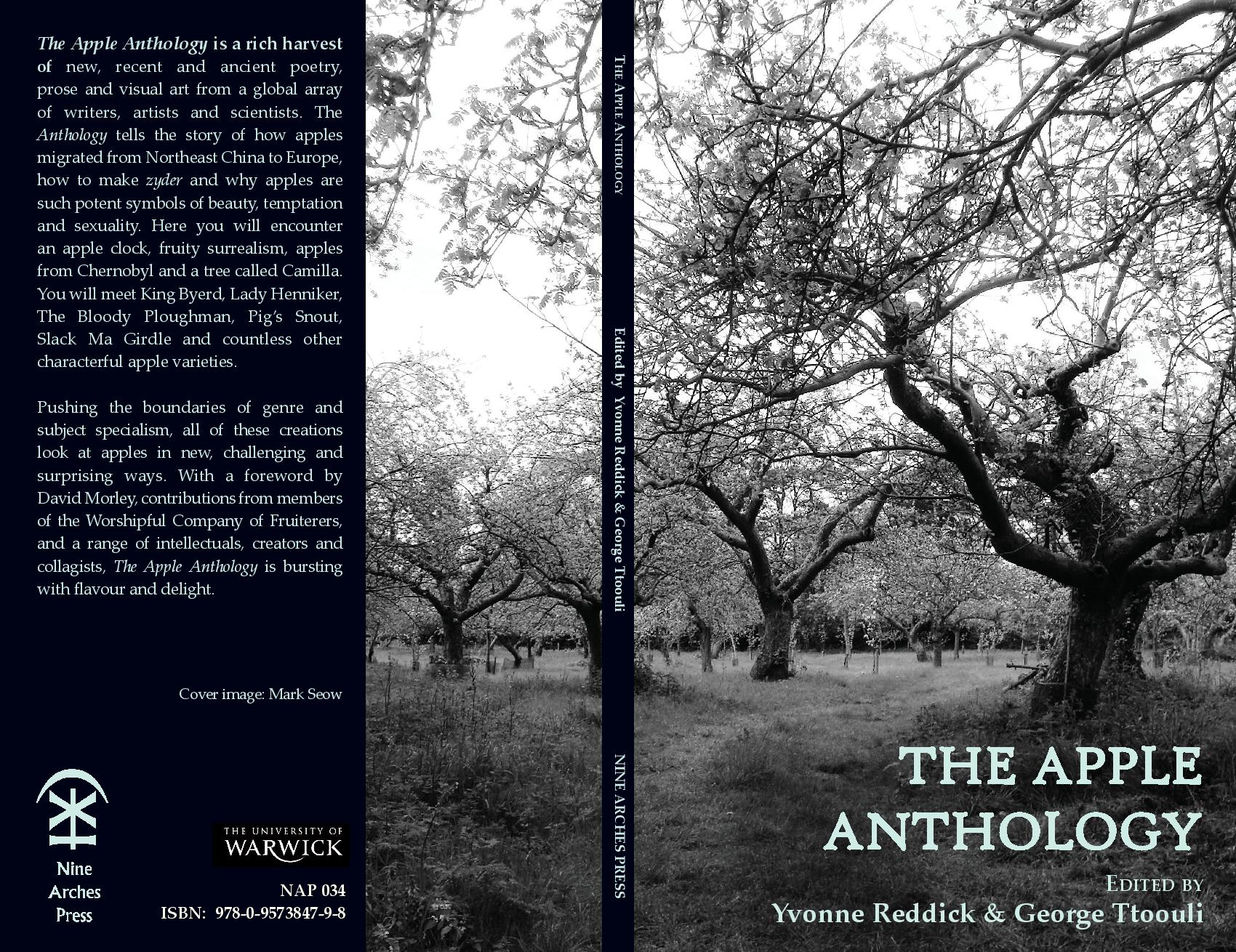

The Apple Anthology (ed. Yvonne Reddick and George Ttoouli)

-Reviewed by Seán Hewitt–

The humble apple has a lot to answer for: the fall of Man, the subsequent subjection of Woman, the discovery of gravity… It has been subsumed into the everyday workings of our language: ‘the apple of my eye’, ‘apples and oranges’, ‘the Big Apple’. Nine Arches Press’s new anthology, edited by Yvonne Reddick and George Ttoouli, at once traces the ubiquity of the apple in world culture, and continues the process of its mythology.

By moving between original and translated poetry, essays, drama, interview and graphics, The Apple Anthology aims to ‘refresh our comfortably wizened notions about this most familiar of fruits’. It should be noted that, due to copyright reasons, the anthology consists solely of ‘first-fruits’, ‘biting into centuries-old textures and symbolisms’ in order to carry the apple’s profound literary history into 2013. However, the consistency lent to the book by a single theme is not always mirrored by a consistency in quality.

Among the poets, Joel Lane and Adam Crothers stand out from the rest, and the apple comes to mean something in their poems in a way that it doesn’t in many of the others. As a symbol, the apple seems to be prone to conjuring nostalgia, and it was where this was kept in check that the poetry really started to flourish. In ‘The Winter Archive’, Lane’s imagery takes the more obvious trope of peeling (less successful in some of the other poems) and turns it to a new advantage. In an orchard, ‘The black apples under the trees / had been peeled by frost’. The archival nature of the apple’s scent, which stores a ‘cold message / of decay’ pays heed to the potential of nostalgia whilst simultaneously refusing it.

Likewise, in Adam Crothers’s ‘Apfelschorle’ (an apple-flavoured German soft-drink), the focus is on subverting the familiar ‘Hay and apples, apples and hay’ associations. The intentional bathos, from ‘the suns of the golden apple-bubbles’ to the uncomfortable final line (‘Please, Hippomenes, off your knees. Your date-rape drug’s docked in your trachea’) completes the overall arc of this subversion. Crothers’s wordplay, and the semantic progressions and relapses it finds between words, seems effortless, and his poetry moves deftly between witty meaning and meaningless wit. It sets the bar high, and even some of the anthology’s better-known names don’t rise to the challenge.

The essays are well-spaced throughout, and give wonderful insights. The editors have certainly cast their net wide, and the range of their selection really does the anthology credit. From David Morley’s prologue to the book, which meditates on the rich names of apple varieties (a common theme throughout the book, and through ‘apple literature’ in general –Alice Oswald’s ‘The Apple Shed’, for example), through a history of the Bramley apple and on to Campell and Niblett’s ‘Towards a Critical Ecology of Cider’, the work in this anthology traces the apple from seed to cider, and from tree to pie, starting as early as Sappho, stopping in the 18th century and powering forward to the present day in the form of some startling poetry.

This is an eclectic mix, both in terms of subject and quality, and it’s certainly worth a read. However, at times, a fair few of the poems fall for the ease of the pastoral, and uncomplicate their vision in order to achieve a nostalgic, cottagey warmth which is altogether less satisfying. One example is a short poem by Janet Sutherland, entitled ‘Crumble’, which comes near the start of the anthology:

‘I’ve cut out all the rot

the scab, the canker,the codling moths

are flownspot, pox, and worm

excisedmy careful knife

has peeled decayand autumn lies in shreds

about the table.’

The poem is only short, so I have quoted it in full. This is by no means a bad poem, and it works on its own terms. The fact that the speaker has ‘cut out all the rot’ is intrinsic, but the poem does not have the scope of emotion or reference that some other, more fulfilling poems in the book do. It is the fact that the middle three stanzas are essentially elaborations on the cutting out ‘all the rot’ in the first line which means that the poem becomes too grounded. The thought which lies behind it isn’t allowed to fly, and there is no jump towards something more meaningful. The poem exists quite satisfactorily within itself, but it fails to live as a thought in the mind of the reader; it is tethered to the ground by being too careful.

This is probably a question of taste, and it is a credit to the anthology’s editors that such a wide variety of different approaches are allowed a voice within these pages. As with most many-authored collections, there will be things each reader connects with, and things they don’t, but it is always good to read things that challenge, or make you defend, your idea of good or worthy literature. I prefer the tang of bitterness that comes when all the rot is not cut out; others prefer it sweet.