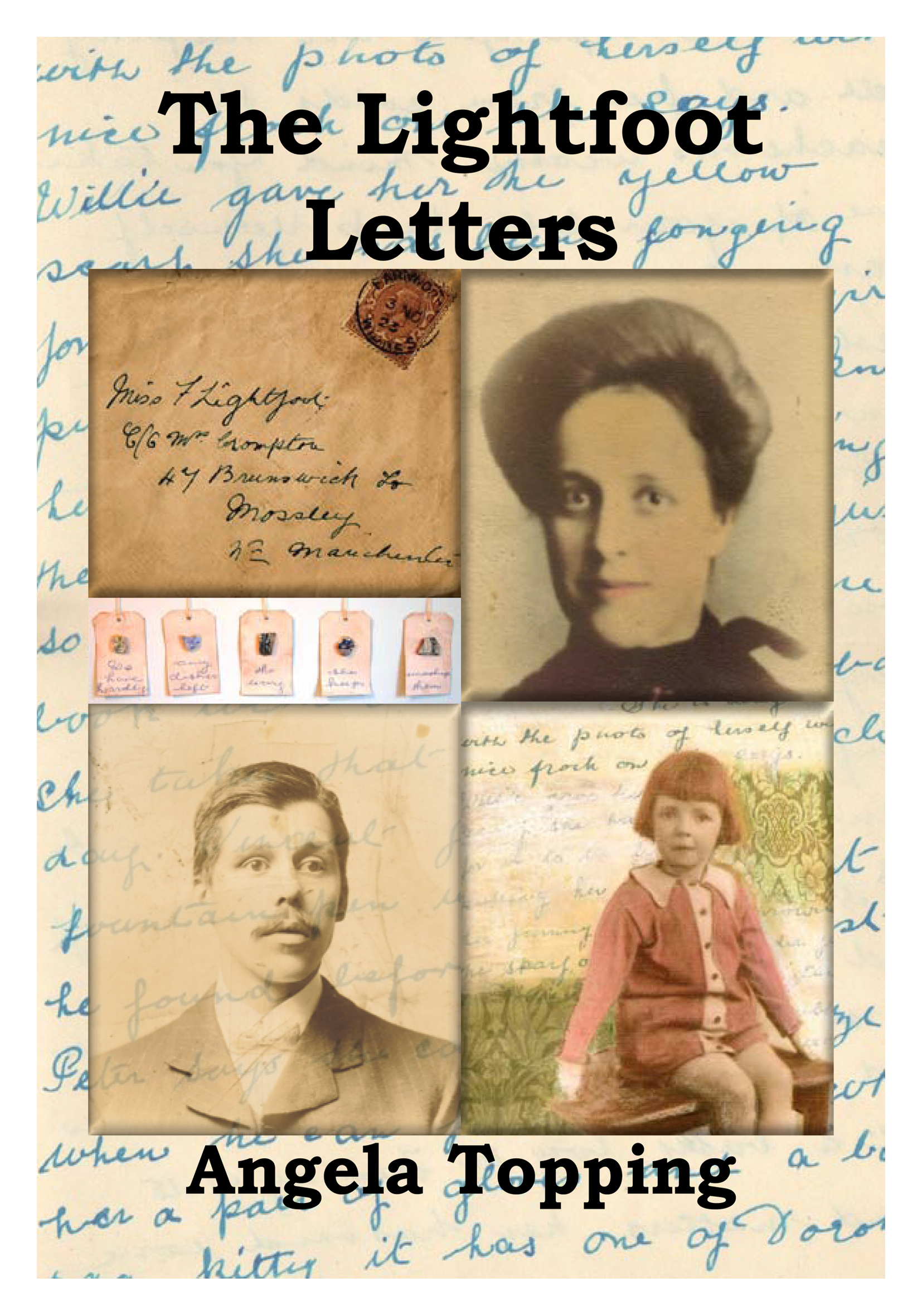

The Lightfoot Letters by Angela Topping

-Reviewed by David Clarke–

The coincidence which was the starting-point for Angela Topping’s collaboration with textile artist Maria Walker, the full results of which will be shown at this year’s Stanza festival in St Andrews, could hardly have been more compelling. In 2009, Topping and Walker met at an arts event in Cheshire and decided to collaborate. Walker subsequently showed Topping some work from a current project using a bundle of letters she had bought in a junk shop. Those letters, it turned out, where written by Topping’s paternal family in Widnes in the early 1920s and were addressed to her aunt Frances, who was living away from the family with relatives. The coincidence was made more still poignant by Topping’s own previous engagement with her father’s life in her collection The Fiddle (1999). As Topping explains in her introduction to this pamphlet, her grandmother’s later illness, which is foreshadowed in some of the letters, meant that her father was unable to able go to grammar school and had to leave education at only 12 years old. The letters themselves do not cover this period in the family’s life, but relate instead to a time before this unhappiness.

The pamphlet version The Lightfoot Letters, published by erbacce, reproduces the bundle discovered by Walker alongside ten poems by Topping. It is intended to accompany the exhibition which came out of their work together, and which has already been shown in a number of venues in the UK. Five of the poems were created for the project, whereas the other five had already been collected in The Fiddle. The pamphlet itself, as a stand-alone publication accessible to those who, like me, have not seen the accompanying art work, raises two key questions. Firstly, how does this personal correspondence resonate beyond the poet’s understandable interest in her own family history? Secondly, what is the relationship of the poems to the letters, and what do those poems give us as readers which the letters alone could not provide?

The first question seems easy enough to address given the current political and economic climate. Although Topping does not make specific reference to this contemporary context, the letters are a timely reminder of the precariousness of working-class lives less than a century ago, when the illness of one parent could be enough to plunge a family into poverty and cut off the life opportunities of young people who, like Topping’s father, had talent but lacked the financial security to develop it. The letters are situated before the worst has happened, but Topping’s framing of them for the reader with her knowledge of what is to come, both in her introduction and in the poems, lends great power to the everyday details and the relative happiness they convey. The letters themselves are certainly not down-beat, despite the first signs of Topping’s grandmother’s illness being discussed: there is talk of tea parties, election meetings (the family roots for the Labour candidate) and a comic account of the perils of primitive dentistry in 1923. At the same time, these remain compelling social documents in their own right, which have much to say about an inter-war world which those who malign the post-World War Two push for social justice would do well to remember.

Although relatively few in number, the poems Topping has included add that further dimension of the poet’s relationship to the material, which in turn provides a lens through which the reader can develop their own understanding. Rather than recapitulating the essence of the letters themselves in concentrated form, the poems offer us flashforwards to Topping’s own memories of her father, grandfather and uncles, as well as imaginative explorations of her feelings towards those relatives, like her grandmother, whom she never knew. Topping’s verse is, on the face of it, emotionally restrained, yet her lightness of touch produces highly affecting moments, crystallising her father’s situation in all of its everyday tragedy. For example, in the poem ‘Father, Skating’, she describes him as a boy, sailing over the ice without a thought for the future, the poet wishing to hold him there just for a moment longer since she knows how that childhood will soon come to an end: ‘Skate on, enjoy the free flow / as your blades whistle on ice. / It’s not yet time to go home.’ Similarly, in ‘Equal Measures’, she describes her father dividing up cheese for his children as he had in his job as a grocer’s assistant as a boy, ‘his knife scrupulous’ as he tries to guarantee them even in this small thing the equity which has been denied him. These poems never preach or tug mawkishly at the heart-strings, but their impact, in conjunction with the letters, is considerable.

My only quibble with the publication, which barely detracts from its value, is the presentation of the pamphlet itself. The letters and poems are crammed in, with the poems sometimes two to a page, or sharing a page with part of a letter. This is doubtless for reasons of economy, but I did feel that the poems needed more room to breathe. Perhaps a keen-eyed publisher will offer Topping a more extensive edition, maybe even incorporating Walker’s art. This would be welcome. Also, it must be said that the opening poem, ‘On First Hearing of the Letters’, did not seem to do much more than set out the premise already provided by the eloquent prose introduction. This appeared to be something of a false start, which was a shame given the high quality work found elsewhere in the pamphlet. For those attending Stanza in March of this year, Walker and Topping’s joint exhibition will certainly be worth a viewing.