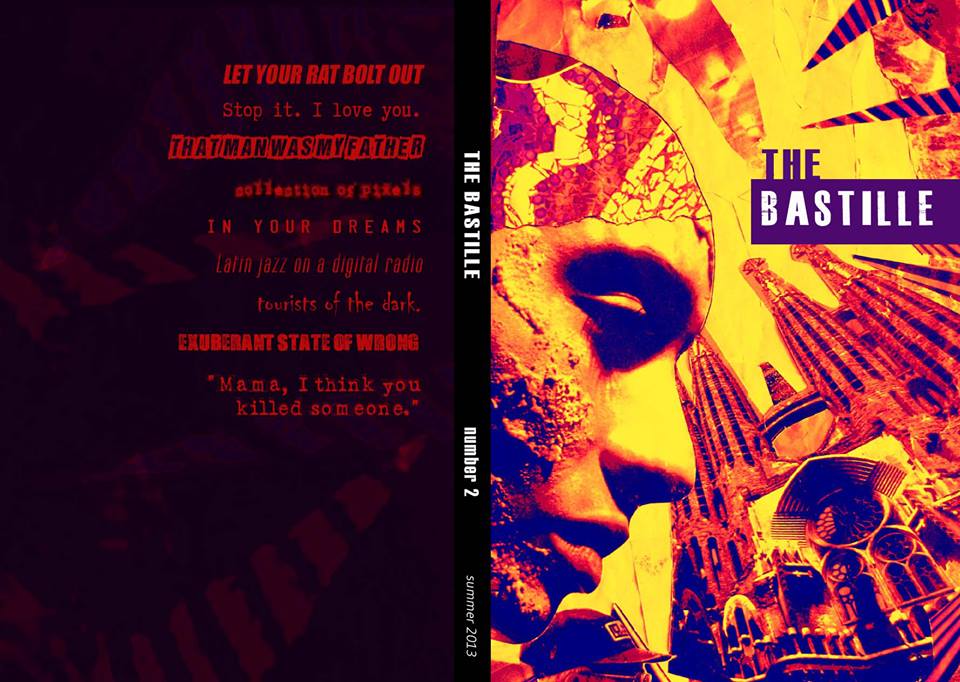

The Bastille #2 (Summer 2013)

-Reviewed by Afric McGlinchey–

The Bastille is an independent literary magazine published by the non-profit organization, Spoken Word, in Paris. This journal gives us more than a ‘vertical understanding of poetry’, as Heaney put it. Here we have tripwire imaginations letting loose on the page, doodles and caricatures, gravity-free, tipsy, somersaulting poems. There’s diversity too – but for me, the best keep their poetic feet firmly in the equivalent of divers’ boots.

The contents page is creatively composed of lines taken from the poems, with varying typefaces which look as though they’ve been ripped from random magazine pages, rather like a note sent by a kidnapper. ‘Let your rat bolt out’ is the title of one section. ‘Tourists of the dark’ is another. ‘Exuberant state of wrong’ is a third. They’re all provocative. The image at the beginning of section one is a collage of body parts, torn strips and repeated images. The impact is dynamic. The bios are fun too, with contributors offering unexpected morsels about their lives as well as the usual list of publication successes. For example, ‘Lisa Paso has been thrown off a train in Belarus, eaten the world’s best pigeon pie in Marrakech and been cheated in the Venetian gambling halls of Ca’ Vendramin Calgeri…’

The poems and prose pieces have been selected, we are informed, for their ability to ‘trigger an experience’, and the editorial team invites the reader to take a journey ‘into yourself’. There are ‘structural arcs’ or sections which create a sense of order, so that the weave an overall pattern or story.

On the Call for submissions page, we are told that the editorial staff is ‘eclectic’ with varying tastes that ‘run wide and deep,’ and I found this to be the case. Many poems represent the current trend towards extended, dense fragments, while others are more cohesive narratives.

With this aesthetic bias towards the incomplete, these might appear dangerously automatic, or ring a false note. At times, however, the poems can work magically, electrically and, what do you know, sometimes even rhythmically. They can create, if not narratives, then dramas. But the whirling concentration of images sometimes falter, turn rote, until there is little to explore beyond the first reading. The ambience after the first rush becomes static. Nevertheless, there is seductive and powerful poetry here too, particularly when there’s a sense of the poet’s actual experience, a concreteness and genuine meaning, such as in Lucy Gellman’s ‘The dissection’, a detailed and visceral prose poem that manages to avoid sensationalism: ‘Whole sponges of lung flaked on our gloves.’ Kathryn McMurray’s poem ‘period.’ is another:

Do you hear me old mother?

Here’s what I want to do: destroy, smash and burn

that old clock. Hear me? With your ticking and tocking,

I’m done.

‘Make every passage you write a foreign city’ writes Howie Good in his poem ‘Stéphane Mallarmé speaks to me in a dream’. And he does, very effectively. A line from Claire Trévien’s, poem, ‘good god that’s a lot of shake’ gives us the title for this section, her language as alive as an electric charge: ‘In unlit alleys/your skin is taut/like a bin liner,/you rip it open/and let your rat/bolt out.’

The poem ‘prima hora’ by Curt Hopkins appears naively romantic initially, with words like ‘flowering’, ‘pewter dawn’ that ‘silvers’, ‘gilded by the sun’ – but then there’s a sharp reversal, and the ‘joyous expectation’ is halted in its tracks, just in time to save the poem from being overly lush.

In the section titled ‘Mama I think you killed someone’, Ken Kashim’s absurdist piece, ‘Hell is light’ highlights the mechanical processes of a regimented society. Vivienne Vermes enters the mind of a fearful child in ‘The house that swallowed people’, and the title of this section comes from her piece. A sense of dislocation, avoidance of real emotions is the theme of the eerie, futuristic ‘Button Boy by Carmen Martines.

Much of the writing here deals with the blurred sensation of co-existing with both the physical, concrete world and the unstable mind. In Jonathan Schiffman’s story, ‘Vassilis returned home from work one day and thought it would be a good idea to stick his arm up his ass’, the originality and shock factor of the content propels the reader on (along with his arm). The bizarre, surreal, visceral description of this act (which goes further) is intriguingly contrasted with Vassilis’s usual controlled, possibly OCD behaviour of obsessive neatness. Another story in this section, ‘Observing the Observatory’ by Bibi Jacob, deals with a giant hand that comes down, peels open the observatory ‘like an orange’, then disappears ‘back into the ether’. Judicious placement by the editors then, or perhaps they were both participants in a themed workshop exercise?

In ‘White Endless’, Merve Pehlivan writes, ‘There is a strange sadness in watching love / dissolve into thinning days’, equating the experience with the colour white, or the number zero. This poem is well-placed next to Erik Bertilsson’s ‘The Satisfied’, where the speaker creates a strange dislocation with slashes/contradictory feelings to express ‘the fatal factory of desires’.

The section ‘Exuberant state of wrong’ offers a profusion of images and a downpour of past experiences which are drowned in martinis and bourbons in the stylish ‘Tonight, forgive me’ by Lisa Pasold. In Jennifer Pinard’s ‘In my first eight lives’ the speaker has finally learned not to trust naively in apparent solidity, but to ‘knock at air to be sure / it has not been painted there.’

While the language in some of the poems doesn’t leap from the page, there is tremendous power in the (apparently) confessional form, such as Alberto Rigettini’s ‘That man was my father’, where the conflicted emotions of loyalty/duty vie with overwhelming murderous urges: ‘he is still strong enough / to grasp my throat in a chokehold tonight / as I dream his death.’

Clint Margrave’s poem ‘Stellar outcasts’ magically sweeps the reader into the ‘interstellar deserts of the Milky Way’, and his image ‘Tourists of the dark’ is taken for the title of one section. A Gulliver-like scene is described in Yann Rousselot’s fantastical ‘The Museum of Miniatures’, where ‘I squash a tiny pedestrian / and lift my foot and find a patch of red there’.

Jeanne Simonoff’s ‘I dreamt of her’ is a list poem, recreating a happy childhood, which grows more poignant until its ending.

‘Quiet, you skeptics’, a poem by Evan Knight, includes small bottles of shampoo in a fantasy flight to Spain, simply ‘to please the detail-oriented mind’, while Spain is sensually evoked in ‘the jasmine-drenched labyrinth of narrow /old-city streets’. The lovely ‘Eclipsed’ by David Leo Sirois describes how,

not addicted to being noticed,

the moon’s gone – then it unwraps

the dustless surface of its glass,

wanting nothing but to want

the light that eclipsed its antique mask.

Also from the section ‘In your dreams’ (as with the above poem) there is Rethabilo Masilo’s beautifully subtle, textured ‘There is music’ which captures the combined pain of pleasure, memory and longing: ‘his fingers flew, or seemed to fly, / surprising every key in its sleep /with a kiss’.

I wish I could mention the work of all the contributors, but you’d never get to the end of this review. And besides, it’s good to leave a few surprises.

All in all, reading this journal is like diving into a bizarre lucky bag of confectionary. The Bastille is a great platform for writers to push the boundaries of what’s possible with both language and form. These pieces offer an immediacy of experience and sensation that is refreshing, if occasionally shocking. That’s what you wan in a journal. Variety. Surprise. Amusement. Illumination.