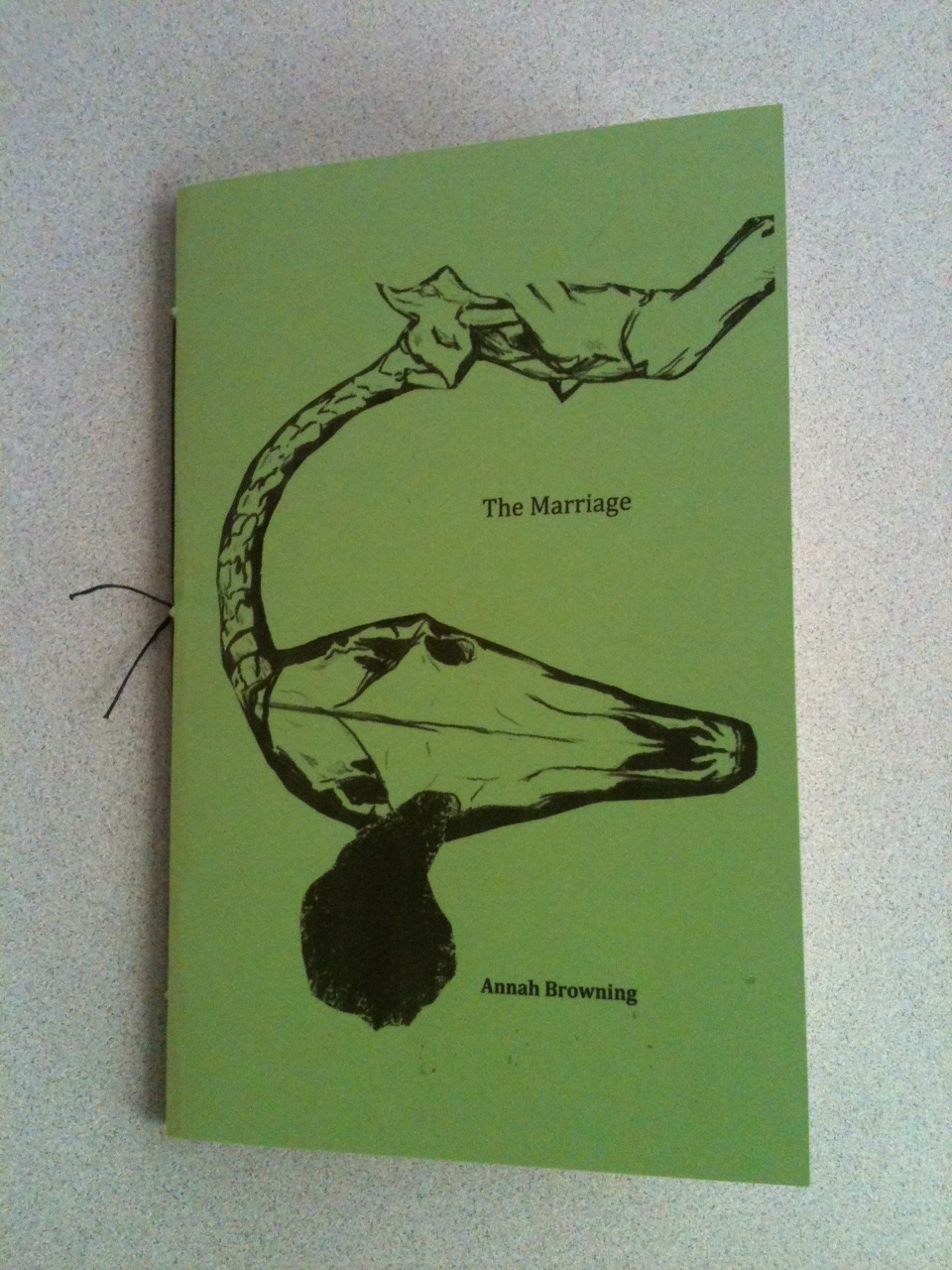

The Marriage by Annah Browning

-Reviewed by Caroline M. Davies–

Annah Browning’s The Marriage is a chapbook of twenty poems dealing, as one might expect from the title, with the institution of marriage and its aftermath. Many of these poems are filled with foreboding. The opening poem, ‘Dear One afternoon in January’ ends with the lines

– we’ll walk over them,

we’ll talk about naming them.We’ll let them hurt us.

(‘Dear One afternoon in January’)

The men who appear in these poems are ones you wouldn’t want to have much to do with. They are murderers in ‘Flat Hills’ or an arsonist in ‘House-Sitting’. The closest you get to acceptable is the character who appears as ‘The Pet’, one of the few poems in which the narrator has a semblance of control.

Let me clean your glasses

for you, evil pet of mine. I’ll

take you tweedly, intomy lap. Wrapped up in your own sleeves

[…]

How could I leave you frozen

when there are so fewothers? How could I turn

the whistle away, when the windopened up my door?

(‘The Pet’)

Nevertheless the trajectory of the book is towards hope, as the narrator begins to find herself and to escape.

I have to make

a slow majestyout of refrain, the same

water slapping the same(‘Dear John’)

I cross my arms above

my chest. I will notbe blessed, I will not have bread.

I go into the corridor(‘Prodigal’)

The animals that appear in the poems like the fish in ‘Lake’, a horse and a sled in ‘The Winter’, the cicadas in ‘House-Sitting’ bring messages and hope. It is the starlings in the final poem ‘Home’ who provide a resolution

Starlings recreate the city.

It travels. It changes.

These poems come across as ones which were set down with speed. You can feel how much Annah Browning loves words and letting them all flow out. However as a reader I was sometimes left feeling as though I hadn’t been given the key to what these poems were about. I found myself wishing that they all had the clarity of ‘Anniversary’:

Sometimes, you fall in love

with the man who killedyou. You want to be close

to him. You want to feeland fondle his ears.

rather than ‘Thursday’s Child’. In ‘Thursday’s Child’ there are things which you can see clearly ‘a man who left / his overcoat on the stairs’ and ‘the polished knob of a bed’ but then veers off a lines like ‘The talent of larkspurs / is that they are not larks’.

It is fine to write poems as a discharge of energy (as Browning comments in an interview online) but you should go back later to consider what this might mean to the reader.

Annah Browning favours two line stanzas, usually with the second line indented. I did find myself wondering whether she’d considered experimenting with longer stanzas. If I was in a workshop considering a few of these poems rather than reviewing all of them I might take the opening of a poem like ‘House-sitting’.

There is a man inside

the house, teachingthe living room how to burn.

He has already

and suggest removing the stanza break so that the man teaching the living room to burn is all in the same stanza. But perhaps Browning is deliberately using stanza breaks in this way to show the fractured relationships in the poems? A chapbook is sufficiently succinct for her to pull it off without it seeming too much of a habit.

The poem which I kept going back to and which became my favourite of the poems in the book is ‘Lake’. This is half way through the chapbook and represents a turning point. It also encapsulates what the book is about, discovering your own way through life even when it threatens to imprison you.

I keep walking into myself

Stillwater. This is not a lakefor knowing. This is not a lake

for known. I rub outmy face on the water, it comes

right back. One of the fish,he asks me Do you go to sleep

every day?