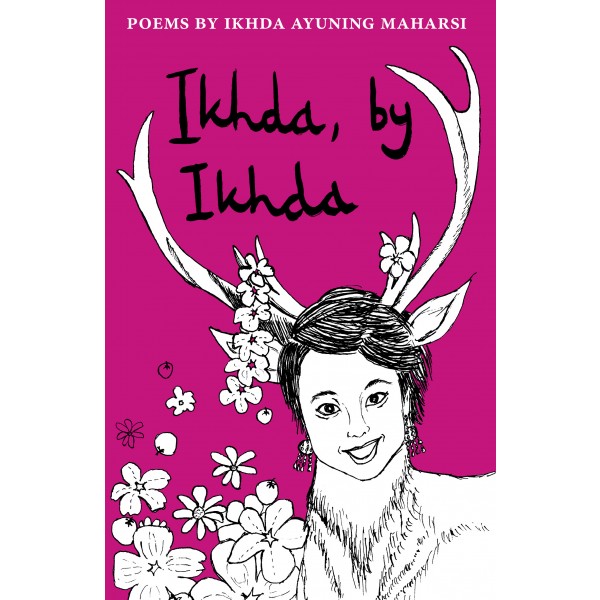

Ikhda, by Ikhda by Ikhda Ayuning Maharsi

-Reviewed by James Mcloughlin–

Don’t tell me about my roots

or my life before this

Don’t tell me about my unopened buds

Ikhda, by Ikhda is fresh air on the page. The collection is bound by the tumult of language and expression as it travels through the everyday-turned-surreal to the touching and tender will of a mother to her son. Ikhda carries a voice into her poetry that is not afraid to love, to be vulnerable and to challenge. Perhaps most indicative of this is ‘Analogy’, in which she lays out the hopes and fears tied to her son in raw and unflinching honesty: “I hope you don’t have the courage to hurt anyone”. This is about as heart-warming and simultaneously heart-rending a line of poetry as you are likely to read and is followed by the adventurous optimism that, while the world may not be “as warm and funny as your mother’s womb”, there are still many opportunities to explore in the “playground” of life. This kind of parental optimism might be overbearing and preachy if done to excess, but here, amongst the playfulness and occasional brutal confrontation of injustice, it heightens the pieces around it by its willingness to lay bare the trepidations of the author.

‘Amnesia’ is one such challenge to received wisdom that weaves a teasing light-heartedness into its tapestry of confrontation. Solea, its subject, “is as illogical as a lottery”, with her belief the she herself belongs in the kitchen, amongst other such regressive outlooks. It’s a sentiment that would appal those who campaign against such oppressive schools of thought, but she lives with a purity and euphoria that those same campaigners, in their ‘enlightenment’, may seldom feel. It’s a message that flies in the face of all our progressive ideologies and yet it begs us to consider that blissful ignorance is not as detrimental, on a personal level, as we want to believe.

The voices may occasionally sound shoe-horned into a collection awash with diverse characters and adventurous settings; but it is not to the detriment of Ikhda, by Ikhda as a whole. On the contrary, it celebrates experimentation and a willingness to forge something unique for the writer to be defined by. Too many poets are flowery and elaborate without ever eliciting an emotional response from the reader. Try remaining unmoved as the girl tending her market stall in ‘Afterbirth’ rails against the oppression of silence, which manifests itself in the form of a meat-thief. Excruciatingly, the ‘beautiful Turkish girl’ cannot eke a response that approaches justice. Ikhda’s great strength as a poetic storyteller is perhaps best demonstrated here – in a seemingly banal setting, with little background or context, we are drawn to empathy for the girl, prodded to angry righteousness by her desperate politeness in the face of the apathy that surrounds her.

There are themes strung strikingly between the pieces in this collection; the body’s anatomy, fingers, flesh. All of these are prominent throughout – particularly in ‘Appetit’ – and notable by the focus on their transience or mortality – an over-arching concept with which Ikhda revels in moulding into a cacophony of visceral character studies. Prevalent, too, are the images of journey and re-birth, and how the absorption of culture and experience can lead to a purity of character similar to being born once more. See the brilliant, marching ‘Atlas in Ubud’ to find this most evident.

Wherever one happens to dip into this collection, you can be guaranteed a blend of refreshment and anger, conflict and peace side-by-side without ever appearing at odds. Ikhda herself has conjured a fantastic tree of poetry, branching out and blooming on the strength of her conviction as a writer of innovation and sentiment. While some of the branches are barren – the frustratingly pedestrian ‘Ancient Victoria’, for instance – this does not subtract from the vibrancy and joy running through Ikhda, by Ikhda one bit. This is a collection to confound, to expose, to liberate; indeed, the author’s note expresses a desire to ‘free the prejudices of every reader’. Read it. Re-read it. Try not to be liberated.