TEMPLE by Kristen Case

-Reviewed by Rebecca Tamás–

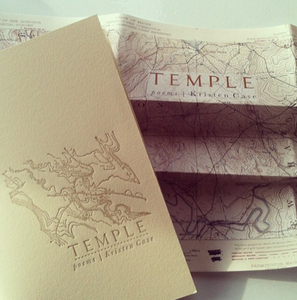

The first thing you notice on picking up Kristen Case’s chapbook TEMPLE is the beauty of its presentation. Produced by MIEL books, a small publisher based in Belgium, the chapbook is hand-bound and hand-printed in thick cream card, somehow delicate and substantial at the same time. This is not however merely a case of MIEL creating a desirable object to encourage us to part with our euro. Rather, the sparse loveliness of the container mirrors that of the poetry inside. This is a book deeply interested in the relationship between word and object, the capability of language to interact with the physical world.

Case is an American poet, the title TEMPLE comes from her rural home in Temple, Maine, and an interest in the particularly of one’s place, the endless variety within its familiarity, runs through the book. Case takes her epigraph from Thoreau, the father of American writing on place and the natural world, and the poems are particularly influenced by his descriptions of working with nature’s agency, of responding to its material language:

making the yellow soil express its

summer thought in bean leaves and blossoms

rather than in wormwood…

making the earth say beans instead of

grass— this was my daily work.

The idea expressed in this epigraph, that what the earth does constitutes a kind of non-verbal saying, a ‘summer thought,’ is key to these poems. For Case the material, earthly and bodily worlds have their own forms of expression, forms which verbal language struggles to do justice to.

In the book it is the perspective of new motherhood that catalyses an awareness of these other kinds of language. The poem ‘Lactoexodus’ registers the alienation of entering an infant world where the body take precedent over the mind, describing a poet’s exile from verbal language.

For a time, my body made milk, and I wrote no poems.

For a time, I made milk, and my body wrote no poems.My body said milk.

The poet has not lost the power to express herself, but her expression is now fleshly, rather than intellectual. Case maps this newly wordless territory with startling clarity and precision in the poem ‘On Silence And the Desire for Silence’.

In the months before my son made intelligible sounds,

we shared, sometimes, a perfect solitude.

It was as if language were a house

that I could walk out of.

Of course Case does not walk out of the house of language permanently, as proved by the existence of the poems themselves, but her experience of having a child has shifted language, it can no longer be trusted to provide complete expression. What were once fixed and predictable systems of grammar and syntax become porous, fractured.

I do not know how to tell you

what the presence of another body

inside your body does to the

grammar of sentences…

A fine shattering, a warm translucence.

Case has seen and felt spaces which words cannot access, and this gives her poetic language an awareness of its existence alongside a set of other kinds of voices, bodily and earthly, which have their own agency beyond the linguistic. The chapbook traces this transformed view, evocatively describing the gaps that exist between our human understanding and the reality of the material world. This is language that manages to register the silence which it itself contains, the space between the word and the object it attempts to know.

Between letters and other letters, between birds and the

body of air, between the covering that is called skin and

the covering that is called clothing…

between these our sundered bodies.

Case’s poems are humble, precisely describing a loved world, whilst also making the reader aware that this world can never be perfectly captured in language, that the reality of the object is always partially obscured by our human subjectivity.

before I notice

the way the water meets the thin, clear edge of ice

in a pattern of fractal protrusions

or the way each of these

is hung with drops of bright glass…

I have made it a figure

for what I want.

In laying bare a passion for understanding the material world that language can never fully satisfy, Case is able to make poems which respect the independence and difference of that world. Her poetry records non-human and natural things without trying to contain them, or force them to exemplify any kind of transcendent meaning. The book is peppered with simple lists of place names, underlining her attempt to let language speak of what is, as it is.

Drury Pond

Varnum Pond

Staples Pond

The place names here register the human desire to describe, and yet none of the descriptions change the ponds from being ponds or can explain to us what being a pond is. Case manages to unhook language and thing, and so reveal to us the gap between human understanding and objective reality. In doing this Case’s poems paradoxically do justice to the reality of the non-human that we cannot grasp, allowing language to be flexible, to admit to what it cannot know.

Case has created a stunningly original poetics which expresses the strangeness underneath the surface of our everyday world, a material agency which language can never contain, but which it can make space for. Case’s Temple avoids deities, rather keeping its adoration for the immanent, imperfect, tangible world of things.

All night the bareness of things presses in:

fir tree, floorboard, wound.…

See how tenderly

the page touches them.