Young Skins by Colin Barrett

-Reviewed by Rebecca Burns-

Young Skins is Colin Barrett’s debut collection of short stories. It is published by The Stinging Fly Press and comprises seven tales in total. About 180 pages long, it is one of those rare pieces of fiction: a crackling, blazing set of stories, written in language both jolting and poetic. The book won the Frank O’Connor short story award earlier this year, with Alison MacLeod, novelist and on the judging panel, quoted as asking ‘How dare a debut writer be this good?’ I’d already earmarked Young Skins as a book to read following Barrett’s win, wanting to see for myself just what it was about this collection that so impressed the judges. For almost all of the stories in the collection, it was obvious.

The collection is set around a group of characters who live in an Irish town. Mostly bored, detached, and young, the characters engage in casual sex, violence and drinking. Yet this is not a polemic about disaffected youth; rather, what struck me from the opening passages of Young Skins’ first story was the empathetic portrayal of the protagonists and their situations, which chime with the reader. The first story, ‘The Clancy Kid’, blasts off with searing honesty: ‘It is Sunday. The weekend, that three-day festival of attrition, is done. Sunday is the day of purgation and redress; of tenderised brain cases and see-sawing stomachs and hollow pledges to never, ever get that twisted again. A day you are happy to see slip by before it ever really gets going’. We’ve all lived that kind of weekend. This is very, very real writing.

Violence permeates the pages. In ‘The Moon’, Martina Bolan, the sexual interest of the character around whom the story revolves, shows up for her first night at a bar ‘sporting a pair of knee-high leather boots and strategically gouged pink tights, hair dyed to a high orange flame, and a murderous glint in her eye’. Others characters have brutal nicknames: Bat, Arm, and shocking cruelty erupts from nowhere. For example, in ‘Stand Your Skin’, Bat is disfigured by a random kick in the face as a youngster, thus changing the course of his life. Even mundane tasks glitter with venom. Bat has problems with his contact lenses: ‘his eyes mildly burn; working his contact lenses in this morning, he’d subjected his corneas to a prolonged and shaky-handed thumb-fucking’. This line, among many others, made me snort out loud.

Barrett’s characters are not paper-thin or two-dimensional. In casual, easy lines, he conjures up rich impressions of the men and women stalking his stories. An elderly woman is ‘a sweet old ruin of an alcoholic who spends her days rationing gin on their ancient, spring-pocked settee, lost in TV and her dead’ (‘The Clancy Kid’). In ‘Bait’, a young man searches women the worse for drink: ‘I heard laughter, the clop of unsteady feet, I saw flickers of hair and shuttering legs’. The snappy description captures perfectly the rapid movement of tipsy women. In ‘Stand Your Skin’ an individual is described as having a ‘spotty face like a dropped Bolognese’. These are visceral images – the reader can visualise Barrett’s characters clearly.

Barrett’s descriptive power is, for me, the book’s strength. His characters are painted with an unsavoury edge, but are the more convincing for it. Even Fannigan, the bad guy in ‘Calm with Horses’, Young Skins’ longest, novella-like story, is written with a line of sympathy: ‘Fannigan dropped the shirt and vest, and was soon shivering in a way Arm found hard to watch. Fannigan’s torso was pale as milk, his chest hair a scutty fuzz petering down to his navel. His tattoos, in the dark, looked like bruises on his arms’. His vulnerability is raw, but that does not stop Arm from killing him. As an ex-boxer and now hired muscle, ‘Arm had the clear head and cold-bloodedness required by the ring, the knack of detachment’. And yet Arm is also drawn empathetically, and is shown to care deeply for his young, possibly mentally disabled son.

‘Diamonds’ is the one story in the collection where Barrett’s raw, thumping narrative does not rattle through, and we are not dropped into the fully-formed life of the nameless, central character, as in other stories. I missed this about this story, though the loneliness of a transient alcoholic is well written.

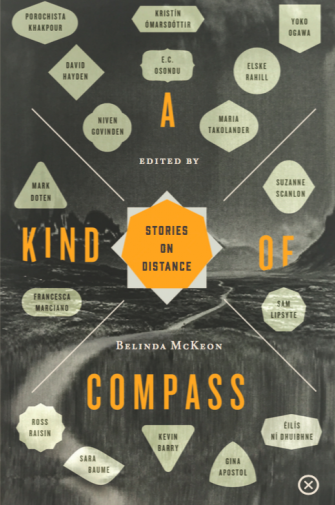

Young Skins is a skidding, breathtaking ride of a book, punchy with humour yet real and heartfelt. The dialogue is crisp and often hilarious, reminding me of Kevin Barry, another Irish writer and recent winner of the Sunday Times Short Story Award. Colin Barrett is a writer to watch; Young Skins is a book worthy of accolades.