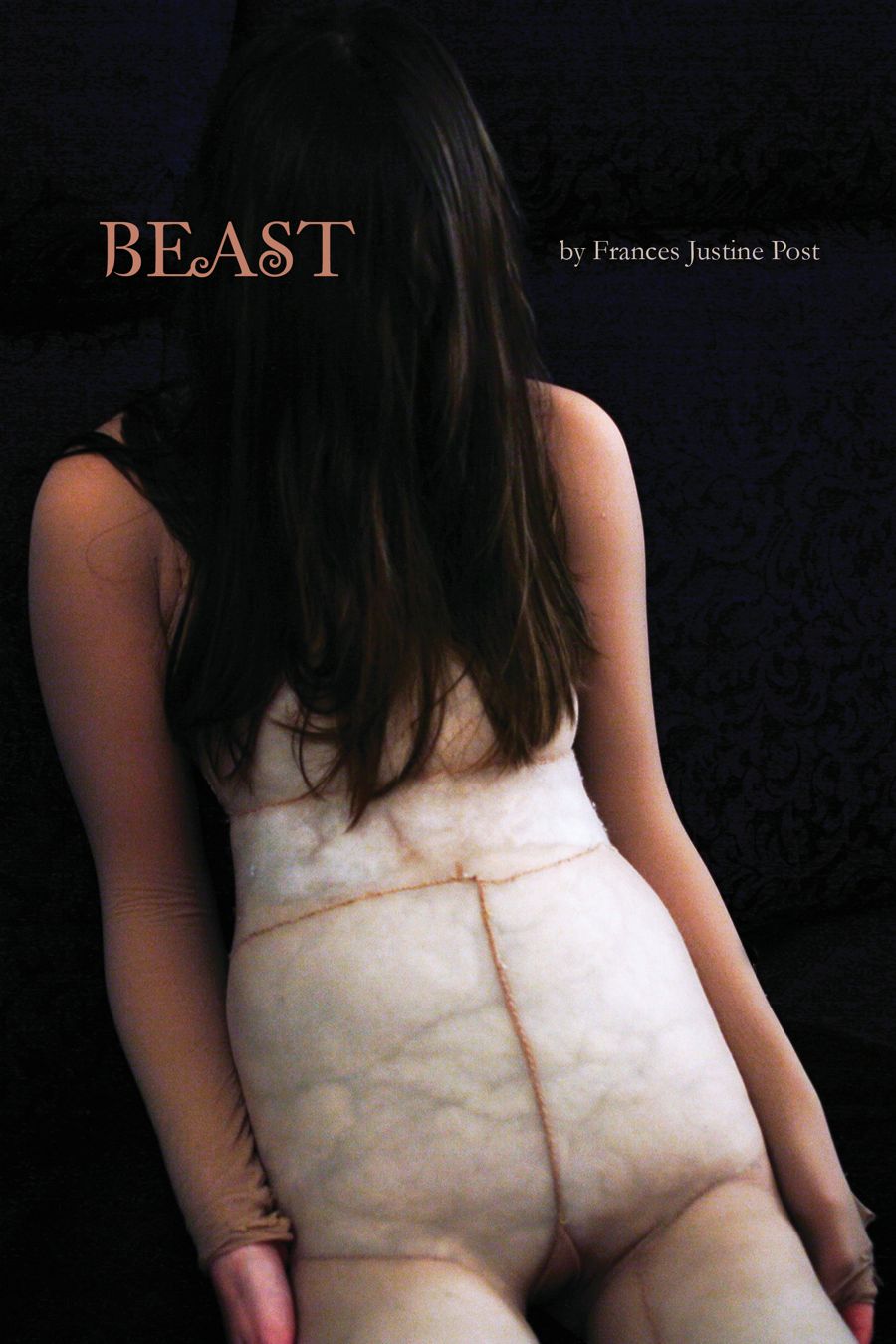

Beast by Frances Justine Post

-Reviewed by Cecilia Bennett-

In ‘Self-Portrait as Beast’, Frances Justine Post’s introductory poem in this début collection, the narrator puts on a series of animal faces. In doing so, she jumps straight into the collection’s central theme of multifaceted self. Overall, Beast is a whirlpool of emotions and images, through which Post forges her own mythology of diseased, hopeless, intoxicating love. The collection is divided into five acts that loosely mirror the five stages of grief, and the reader is drawn in through a wildly fluctuating series of emotional stances. Here violence, turmoil, and anger are mixed with tenderness, and give way to bitter grudge. In this context, the mask motif in ‘Self-Portrait as Beast’ allows Post to explore images that will recur throughout the collection: in many ways this introduction is a map of things to come.

Beast is difficult to review – it is more force of nature than book. It is at times a frustrating read, and I could criticise the collection for its inconsistent tone or for the sheer weirdness of its images, but that would be missing the point. These features are integral to the collection as a whole, and serve only to emphasise the wildly fragmented self that it portrays. In Beast, Frances Justine Post’s poems tell a story from every conceivable angle. To do this, she presents us with a series of surprising self-portraits: ‘Self-Portrait as a Witch’ exists alongside ‘Self-Portrait as Maelstorm’, ‘Self-Portrait in the Shadow of a Volcano’, ‘Self-Portrait in the Body of a Whale’, and even ‘Self-Portrait as the Crumbs You Dropped’. The face of the narrative changes constantly. Read together the poems create a sense of a wider story of torn hearts, conflicting reactions, bitter struggle. In this sense, the collection is very well put together: by encouraging us to fill in the gaps and interact with the book as a whole, Post draws her readers through an intensely intimate journey.

The poems in Beast often address an unseen figure, and as a whole the collection outlines a power struggle between this figure, the object of love and cause of turmoil, and the narrator. The poetry itself is alive with a viscerality that often feels uncomfortably close to the bone. ‘Marionnette’, a poem depicting the narrator as her lover’s puppet, is a good example of this – the body that Post describes is easily manipulated but disturbingly anatomical:

You find my heart – four tough little mouths

inhaling, exhaling with a liquid

mechanical flap –

and push your finger against the currant(…)

Press down on my lungs and they empty

like bellows, outing a rudimentary

language. Let go,

and I gasp as if swallowing

In Beast, this viscerality is often undercut by a tenderness that renders Post’s poetry all the more threatening. ‘Marionette’ is no exception to this, and the final lines –

How my body loved you,

you touched me and the blood

rushed to the spot

to warm your fingertips

– are, in this context, perhaps the most chilling.

This sense of danger never quite left as I made my way through the collection, later a frenzied pack of hounds wonders “What will we do when we have you?”, and the poems are littered threats. Eventually the narrator finds comfort and strength in viciousness. This is no less creepy, and in the last few poems of the collection, the narrator’s empowerment becomes downright threatening. In the last poem, ‘Self-Portrait as Cannibal’ this becomes painfully obvious. Here violence – “I stuck my little dagger in you until the juices ran clear” combines with a disturbingly practical approach: “Every piece of you has its place. Your skin: cut in strips, / braided into a rope that has many household purposes.” The narrator concludes “I don’t need anyone else now that you are here to stay.” The power has shifted.

Frances Justine Post writes in the language of subconsciousness; her landscapes shift and change around her narrator. Here, Post’s strength lies in her vivid and unlikely images that shake the reader’s sense of stability. Beast is very stylistically charged – at times its structure reminded me of a nouveau roman – and it bridges the gap between collection and book. This is a strong and confident début and I am keen to see what more Frances Justine Post will contribute to the world of poetry.