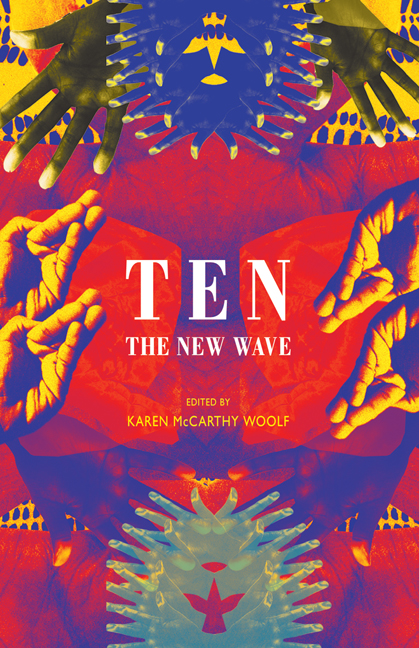

Ten: The New Wave, ed. by Karen McCarthy Woolf

-Reviewed by Sohini Basak–

A poetry anthology titled Ten the New Wave may need a bit of a context for those not familiar with the trends of British poetry publishing and the lack of representation of poets of colour. The remedy was initiated by the writer Bernardine Evaristo in the Free Verse report commissioned by Arts Council England, Scottish Arts Council and Arts Council Wales. Published in 2005, the report asked an impending question: Why have so few new Black and Asian poets been published in the UK in the past 10 years? Since the report, considerable work has been done to bridge the gap including starting a development program The Complete Works, taken up by the organization Spread the Word. A tangible result of this came out in 2008, when Bloodaxe published an anthology Ten: New Poets Spread the Word to represent British black and Asian poets. And the second edition of the Complete Works has brought forward another anthology Ten: the New Wave. Edited by Karen McCarthy Woolf, who was part of the first anthology, this book showcases ten emerging voices from the British black and Asian communities. Karen McCarthy does well to ground the anthology in its overall mission, and the statements from each poet’s mentor also opens up the door to each poet’s works.

London’s first Young Poet Laureate, Warsan Shire, is a perfect poet to start the anthology. In her fearless voice, she writes about dysfunctional families, deferred dreams, about girls growing up amidst limitations and desires. And such tensions between desires and limitations are played out by multiple voices in her poems. For example, the poem “Haram” ends with words that are heard more because they are unsaid:

Some nights I hear her in her room screaming.

We play Surah Al-Baqarah to drown her out.

Anything that leaves her mouth sounds like sex.

Our mother has banned her from saying God’s name.

Jay Bernard is another poet who works with multiple voices to depict everyday episodes hauntingly. Her poem “Punishment” is an excellent deployment of cathartic techniques of tragedy. Joining the troop of visceral storytelling through poetry are Eileen Pun and Inua Ellams. Their long narrative poems exhibit an exciting usage of language. While Pun pushes the visual and verbal potential of the page, slightly reminiscent of Kamau Brathwaite (especially her poem “Some Common Whitethroat Chit-Chat”), Ellams can flip his narratives with punctuation: brackets, forward slashes. Ellams’ selection also exhibits how intra-texuality within poems can make things new. And in these skillful repetitions, Ghetto van Gogh’s voice is heard loud and clear.

Clarity of words and intent is what keeps this anthology so alive. Kayo Chingonyi, for example, is all for “calling a spade a spade” and his sequence of poems under that title is admirably stark. An extract from the section “Normative ethics” puts things in perspective:

In the safe distance of objectivity,

You can speak, with a straight face, of being

on the margins, being thought no longer cool

(if you don’t know the curse the coolness confers):

women who prize your chocolate voice above

your words, or look at you like you’ve deserted

the cause because you are holding hands with your

pale-skinned lady. Men who tut like you’ve stolen

their birthright.

The poets in this collection embrace their diverse identities without fear. They even play with the idea of fear, and introspective irony is just another way to reclaim ground. There is a strong sense of heritage, as well as a sense of immersing themselves in their present territory. Edward Doegar’s “Half-Ghazal” is a beautiful love poem dancing on the borders of heritage and territory, as indeed it dances on the syllables of the poet’s family name. Adam Lowe also merges the then with the now, reworking Sappho, stories from the Bible and Babylon seamlessly, in subversive narratives, claiming them as personal and political points of protest. And when I say diversity, it reaches beyond the scope of ethnicity and literary influences. There is diversity also in the voice of a single poet. Especially in the case of Rishi Dastidar, there is an incredible range of tones, much satire behind the act of licking stamps or making cheese soufflés rise.

As I read the anthology, what comes across most vividly is the wave of a new language. This is the language of belonging and estrangement and most definitely a language of redefinition. Mona Arshi, for example, weighs on grief and loss and there is perhaps a hint of the willful articulation of Sujata Bhatt’s “Search for My Mother Tongue” in her poem “Notes Towards an Elegy”

I’ve forgotten what silence feels like.

Tongue loosened with no protest,

my other tongue, a ceramic figurine,

presses against my teeth.

A tussle between the mother/ other tongue is the starting point for Sarah Howe’s prize-winning pamphlet A Certain Chinese Encyclopedia from which her poems in the anthology are excerpted. Her poem “Others” opens in these essential terms: “I think about the meaning of blood, which is (simply) a metaphor; / and race, which has been a terrible pun.” Meaning and metaphors muddle up to make new ground for growth and possibility much like the multiple hands on the cover from Jay Bernard which makes us see the new shapes that emerge from the gaps between the fingers and what happens when they are joined.