What the MacGuffin? A conversation with Jim Hinks from Comma Press

– interview by Will Barrett –

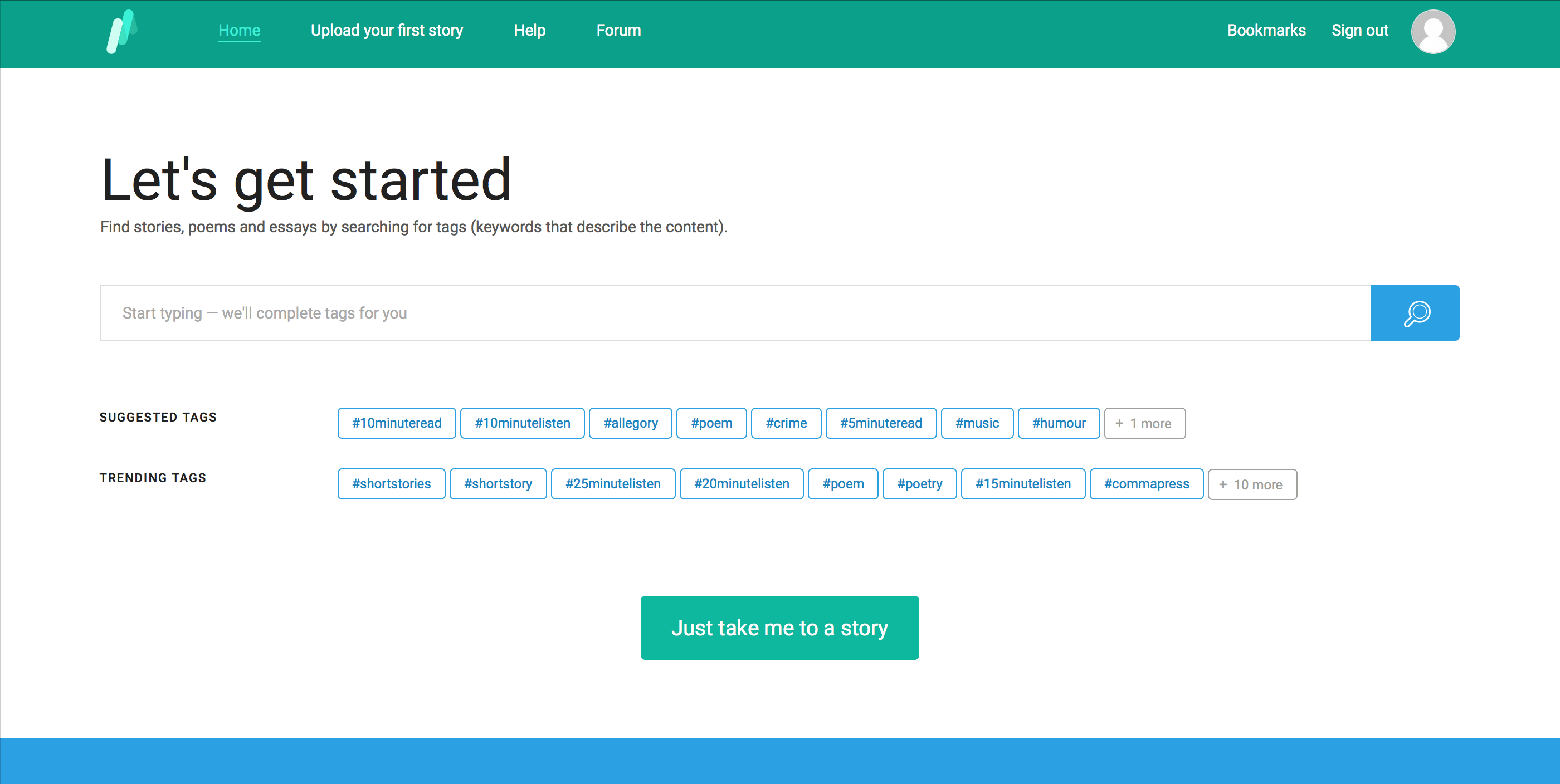

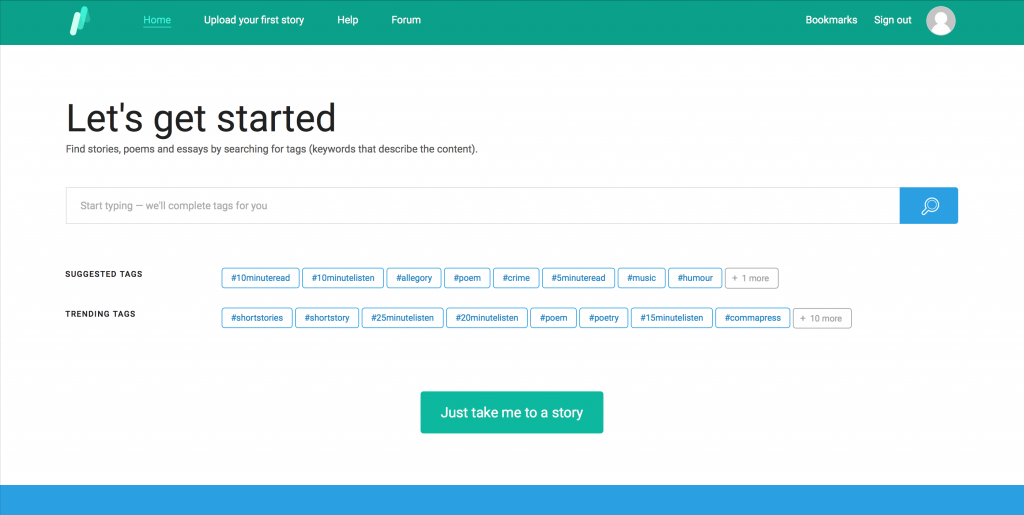

I first knew about Jim (above, racing towards the future) when I heard him talk on a panel at the Digital Utopias conference in Hull earlier this year. Jim is the Digital Manager at Comma Press, and also the project lead on MacGuffin, a new website, currently in beta, where you can upload short fiction and poetry onto a massive, stylishly designed database that is fully searchable and allows multiple ways to sift through content. Writers have been able to make their work available for free on the Internet for many years, and there are countless established websites, platforms and messageboards with considerable communities attached, but MacGuffin offers a few interesting new finesses to the model: an emphasis on audio, fully customisable tagging, access to analytics and reporting tools, and, arguably most importantly, a super search function that can very quickly be configured to filter down to exactly what you want. And that’s one of the promising things about this ambitious project – online fiction is alive and well, but it’s often unruly and scattered across the blogosphere. With enough take-up, MacGuffin could finally centralise a lot of this disparate, floating creative activity which so often is too hard to discover online unless you already know what you’re looking for.

I was interested to know more about MacGuffin, so I sent Jim an email about whether he’d like to do an interview, and as two people who are as into the nerdy back-end stuff as much as as the creative side of things, we hit it off.

Full disclosure: this conversation contains several references to CAMPUS, a website that I work on in a professional capacity. Jim was very keen to make this interview an open conversation between the both of us, where we could both share our experiences creating, designing and moderating creative writing portals in an informal manner, rather than a traditional Q&A. So, conscientious as I am about the danger of moonlighting, I felt some discussion of my own work was appropriate in context. However, in the interests of fairness, I haven’t linked to CAMPUS nor explained much about what it is.

The conversation took place using a chat room in a couple of sessions over two days, concluding on the day of the British General election.

…

If the best thing your favourite book has going for it is the feel and smell of the pages, Literature is in trouble.

Will Barrett: Hi Jim! Perhaps you ought to very briefly describe what MacGuffin is, for those who don’t know about it.

Jim Hinks: MacGuffin is basically a big jukebox for literature. Everything on there is in text AND audio form; writers upload the text and an mp3 of their work. Readers can read the text (via the website or app) or stream the audio (and toggle between the two). The tagging system makes it really searchable.

Will Barrett: Let’s get an idea of the background to this project. How exactly did MacGuffin get started?

Jim Hinks: Well, a couple of years ago, Comma Press (the independent publisher based in Manchester, whom I work for), developed an app for short stories called LitNav. It featured short stories set all over the world. End-users could read the text or listen to the audio. It was aimed at commuters – you could search for stories according to the length of your own journey (and according to other criteria, like genre, location, etc). Although it was a really modest, low budget project, readers really seemed to like it. But the most frequent feedback we heard was from writers, asking ‘How can I put *my* story on there?”

So we had the idea of expanding and improving it as a self-publishing platform. The big lightbulb moment was about tagging and content discovery (with apologies for using the word ‘content’). On lots of platforms (like Amazon KDP, for example), writers upload their work and tag it with keywords to describe it. I might upload a novel and tag it ‘Historical fiction’, ‘WW2’ etc., and then whenever any Amazon user searches one of those terms, my book should appear in the results. I had the idea, ‘What if any end user could tag anyone else’s work, to describe the content.’ Then I realised that with this system, users could use tags to add a story or poem to a personal reading list (e.g. ‘jimsfavouritestories’) or share it with a group (e.g. ‘leedsuniwriters’) or add it to a meme (e.g. sundaysonnets). Then it was just a *simple* case of raising the money, finding the right developer, and actually making it happen.

Will Barrett: So you’ve made LitNav, gotten some interesting feedback about going further with the model and making it open source, and then you made an application to the NESTA Digital R&D Fund right? I’m curious to know what the main arguments of your proposal were, and what specifically were you trying to identify? Because there’s also a research component to this, isn’t there, as much as it is a cool new tool for writers?

Jim Hinks: Yes. All projects supported by the Digital R&D for the Arts Fund need to answer a research question. Our question is can ‘broad-folksonomy’ content curation be applied to literature, to learn about changing reader behaviour and taste? These project each have three partners. An arts partner (Comma Press), a tech partner (fffunction.co, a UX and web design company), and MMU (research partner).

Although, there’s not much point in us building this thing if it’s not going to be fun for people to use. So the ‘cool new tool for writers’ element is not to be underestimated. From a personal point of view, my guilty secret is that, after years of being an editor of other people’s short stories, I’ve recently returned to writing them myself. The idea for MacGuffin also comes from me thinking ‘what kind of platform would I like’? Then trying to build it.

I had the idea, ‘What if any end user could tag anyone else’s work, to describe the content?’

Will Barrett: I completely agree with that. So what sort of folksonomic systems did you look at when developing this? I’m excited by this – all the new micro-genre categories people will come up with…

Jim Hinks: Twitter is a pretty good example, in terms of the way people use hashtags to create memes and lists. It started off as completely alien, and now it’s second nature to people who use twitter. Actually, Last FM was a bit of an inspiration too, though they kind-of buried the tagging system a bit.

Will Barrett: Last.Fm! I always cite that too, although I use it a warning from the past. But it has a really interesting development history.

I think Last.fm failed ultimately, as it wanted to stir up the mainstream but it ended up condensing people’s taste in music, not diversifying it, and I do wonder whether it’s search and navigational system had a huge influence on that. Recommendation engines and top lists can be very deterministic, and narrow everything down to a nub of core tastes. Is that not something you worried about with MacGuffin?

Jim Hinks: Yes. I actually quite like Last.fm, in many ways, but I guess it just lost out to Spotify etc. And since starting the project, I’ve learned quite a bit the slash-fic community (fan-fic erotica), and how they used bookmarking tools like delicious to organise their stuff online (now superseded by archive of our own). There’s a great talk about slash-fic by Maciej Cegłowski, here: http://archive.dconstruct.org/2013/fananimal

Will Barrett: “Fans are inveterate classifiers”

Jim Hinks: Yes, I am worried about that. But music and literature are very different. I can listen to a bar of most music and decide whether I like it or not. This *generally* isn’t the case with literature (unless I read/listen to a passage that’s either really bad or really mind-blowingly amazing). And MacGuffin lends itself to serendipitous discovery too (so rather than condensing taste, it facilitates stumbling across new stuff). For example if you search for the tag ‘ice’ you’re going to find a range of stories and poems with ice as a theme. Some will be to your taste, and some won’t, but it’s fun to surf through them and make discoveries.

Will Barrett: But it’s up to the user to make sure the tags are appropriate. Did you look at GoodReads at all?

Jim Hinks: Yeah, I kind of like Goodreads. It seems like an inevitable site. Though obviously it doesn’t host content. What’s your favourite content hosting site?

Will Barrett: That’s a good question! Wikipedia?

Well, ok this isn’t a pure ‘content’ hosting website, as the emphasis is on content aggregation, but users do bring a lot to it in the ways material is brought together, sometimes ingeniously – and that’s Metafilter. Similarly, I like things like Reddit, Barbelith (now extinct), ILXOR, the Popbitch messageboard. But these are all sites from a certain generation of the web, around 2006-2007, so they’re personal to me. And they’re weblogs, which are old-fashioned now.

Jim Hinks: Ah, okay. In a way, those sites are actually of the opposite of the model for MacGuffin, as with MacGuffin we made a deliberate decision not to have comments (an alternative name I toyed with was ‘nocomment’). What was Barbelith?

Will Barrett: The site still exists, but no-one uses it. It had a very interesting and esoteric creative community: http://www.barbelith.com/

Why did you eventually decide to not have comments? That’s a pretty big decision to make.

Jim Hinks: Something about the comments sections of content-hosting sites seems to encourage people to either be mean to each other, or overly effusive in their praise, like drunks at the end of a party. If you’re a writer, you can get really wound up about this stuff. So on MacGuffin, no wasted time seething about someone’s criticism, or composing your riposte. Rate it, tag it, move on. Be happy! However, having said that, the social media integration is pretty decent, so if people really want to, they can chat on Twitter or Facebook or wherever.

Will Barrett: See I’ve found a different experience with CAMPUS.

Jim Hinks: How would you characterise comments on CAMPUS?

Will Barrett: Initially I was worried about YouTube style trolls lowering the tone everywhere, bringing down the neighbourhood, and there has been a little bit of that, but generally I moderate less and less and interactions have only increased, most of it very genial, generous, supportive. And I’m not sure I buy the argument that people who write poems ore stories are more civilised as you can follow discussions on Facebook between poets and it can get nasty rather quickly.

Jim Hinks: Ha, yes! And also those chats that are like: ‘Oh darling this is so wonderful! You’re amazing!!!!’ etc etc, which probably isn’t all that helpful to the writer, though it might feel nice. You moderate comments?

Will Barrett: Well this is the interesting thing, I used to moderate quite a lot, and now i don’t, and – ok correlation is not causation – but I think being more relaxed about comments and working more on UX has improved the quality and certainly the frequency of natural, organic interactions.

I mean poets on Facebook can be red in tooth and claw when they want to, as with anyone, but I do think it is the way Facebook works, as a physical machine/programme, that encourages sparring more then other online forums. Disclaimer: most poets are extremely responsible, polite people, but Facebook does have a reputation for encouraging verbal jousting. I refer you all to the massive Kate Tempest backlash when they announced the Next Gen shortlist.

Jim Hinks: Poor Kate Tempest. You’d think trolls would pick more deserving targets.

Will Barrett: Most of the community areas on CAMPUS are completely public and everything gets published openly and visibly on the home page area (there are private areas too, that we use for teaching, but they’re facilitated by watchful tutors with moderating capability). Facebook and Twitter are big public sites, but they have more of a discrete feel, like you’re tucked in a nook away from the main forum of activity – many people forget that they’re broadcasting to the entire internet because most people experience Twitter, FB through the filters of their personal timeline. So they feel intimate, but they’re not, which is why footballers and politicians are always caught out saying heinous things. CAMPUS, through necessity as much as design, doesn’t have the same feeling of intimacy, like you’re talking between just friends, which has helped create a global sense of transparency that’s balanced the tone without much external effort. Jurisdiction helps too: I generally encourage people to use their real names, or literary pseudonyms.

Like I say, I personally believe you can hardwire good, progressive behaviour through good, progressive design and UX, and rely on moderation less. Very innocuous-seeming decisions – as small as a like button – have massive consequences to how people psychologically relate with and use a website. This is particularly important to get right with what we’re both doing, as creative writing is often such a personal thing, to have a part of yourself terrorized is pretty traumatic and unproductive.

But it’s not just the Internet where trolling happens; it seems to be a universal way some humans sometimes behave. Think of all those stories in newspapers where standers-by jeer suicides to their death from the pavement below. Allowing anonymity or a safe sense of distance emboldens those tendencies.

Jim Hicks: I agree. I’d be interested to know how much you feel the good behaviour – so to speak – is also a product of the community of users you attract, in addition to the design (or perhaps the functionality & design attracts a better community of users?). You mentioned that poets can still be snarky to each other online, but CAMPUS hasn’t experienced that.

Will Barrett: The community is the most important thing, absolutely. Everything else is window-dressing. It’s the main reason you go to a site, weblog, content publishing platform. Especially with creative writing. This is why MOOCs work less well with creative writing, as close community and social interaction in sensibly-sized groups are absolutely central to the learning process. It’s not like learning maths or physics – the pedagogy involved is very different to create a virtual environment that really impacts on how people read, review and experience literature in way you can’t achieve face-to-face, particularly how to think critically about poems and stories.

I’m not sure CAMPUS encourages a special kind of community other than they are practicing or returning poets, which is our central aim. We are lucky that we’re building on a 18 year old institution with an existing audience, so that’s a good starter. Having an existing community to work from helps to promote general tolerance and respect, and means that the quality of feedback is relatively decent. Although sometimes I think it’s too nice!

Jim Hinks: And yes, too nice can be just as destructive. I’ve workshopped some pretty bad stories of my own and thought ‘I wish people would just be honest – I can see the flaws in it; help me.’ And likewise, sat silently as someone else’s work is critiqued thinking, ‘am I the only one who thinks this is really bad?’

Probably the thing that will require most moderation on MacGuffin is ‘barging in’, as we’re calling it. When a user tags themselves into someone else’s reading list or what-not. I think that will happen a lot, perhaps inadvertently, until people get the hang of what MacGuffin is.

Will Barrett: Yes. You see it on Twitter with hashtag squatting. People gaming the system. And Facebook with people spamming comments with their personal promotions. It’s inevitable, and it’s a hard thing to police because you’re operating an open policy on who can join. Which again is why I tend to prioritise design and community. The technology for all this stuff isn’t that innovative right? It can only do so much.

Jim Hinks: That’s true, and neither Facebook or Twitter have cracked it, so perhaps I’m being optimistic to think we can. We reserve the right to close someone’s user account for persistent breaches, but it needs a kind of green>yellow>red card system.

Will Barrett: I should add – the design of CAMPUS is (open secret) one of the weakest areas of the site, but it still retains an audience in spite of those problems. So a good community seems to be the most important element to users. This idea is reflected in other creative places online, something like the Mudcat messageboards (a hub for folk musicians) which is the least user-friendly thing you’ve ever used in your life, but there’s a cause and a quality/intensity of content and discussion that sustains it.

It’s only in beta so there’s not much of a community on Macguffin yet. So, parking that, what do you think are the really novel, totally unique things about Macguffin and how it works?

Jim Hinks: It feels like the right time for a self-publishing platform for text and audio – amateur podcasters have led the way in recent years, showing that you don’t need expensive studio equipment. If you have a smartphone, you have a recording studio in your pocket. Plus 4G is expanding and getting cheaper, and will soon even be on most of the tube network. If MacGuffin isn’t successful, I can imagine someone else coming along with something similar that is.

Will Barrett: I was going to ask about that – audio is so central to this. Audio content is a really big growth area (my girlfriend is even working on one of a new of exclusive original content pilots for Audible). Is that why you made it such a core part of the Macguffin offering? And do you think people will go for it? It’s quite a big step up to get good writers also become good performers…

Jim Hinks: Ah, yes! To build a platform that offers readers text & audio versions of everything, you have to accept that, at least until people get used to the idea, you’re going to loose 75% of potential writers who aren’t up for recording a reading (or don’t like their own voice, or don’t have time, or think it seem technically difficult, or they just can’t be arsed, which are all legitimate reasons).

But I hope that when those writers, who’ve been put off, see other writers sharing work they’ve published on MacGuffin they’ll be motivated to return and upload work themselves. I hope the motivation works both ways: ‘I could do better than that’, or ‘that’s good; I want my work to be seen alongside that.’

Will Barrett: Start from the edge and work in. Again look at Twitter and how that started. I loved Twitter when I joined – it was full of creative people and discussion – but I can’t abide it any more now it’s so popular. It’s like a pack of angry bees inside my head.

Jim Hinks: “It’s like a pack of angry bees inside your head.” God yes. Did you read Jon Ronson’s So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed?

Will Barrett: No I’ve not read that yet, but I’ve seen some serialised bits here and there. I saw the thing on YouTube about his fake Twitter account and the ‘infomorph’

Jim Hinks: What if that initial user-base is so niche it it puts off more centrist readers and writers? It’s a balancing act. I think having publishers on board (and people like Arvon) should help though.

Will Barrett: So you’re encouraging some competition on the site, then? Is that partly the reason for the star-rating system. To add a mild gaming or reward element to help people aspire towards greater achievements?

Jim Hinks: Ah, gaming. It’s been a bone of contention and still is. Should we make ‘trending’ (i.e most read) stories visible on the homepage, as a motivating factor? Should we make the most recently published story visible in preview on the homepage?

Will Barrett: What are your feelings on that issue? I did note that there was very little by way of curated content on the site, or recommendations/lists, autofeeds of most popular posts. It’s like Medium with all the editorial taken out. The focus is the search box and the metadata – that’s it. Is that deliberate or are you going to deploy other stuff later when you have more stories on the site?

Jim Hinks: Our thinking so far has been to make a lot of this info available in the analytics (which we haven’t even touched on yet) – so any reader can do searches for content with certain tags and see stats on how much it has been read/listened to, what the ‘drop-out rate’ is, and so on. So you could use the analytics to find the trending stories tagged ‘crime’ for example. That functions being added over the next couple of weeks; at the moment the analytics just tell you some basic reading stats for individual stories, e.g. where in the world they’ve been read, what the read/listen ration is, the rating for read/listen, the completion percentage for read/listen, the drop-out points for read/listen. Stuff that’s probably more useful to the author.

If you click ‘just take me to a story’ on the home page, it’ll randomly return one of a pre-selected bunch of stories and poems. But honestly, I’d rather keep my hand off the tiller as much as possible (god that makes me sound like a complete free-marketer).

It’s really satisfying to read stories on there, and tag them jimsfavouritestories the search for that and have them all returned. I can use that functionality to make playlists for other people, or share with a group. If people get that, we’re in business.

The rating system was conceived less as a way of gaming it, but as a way of forewarning readers to bad text/audio. We can make adjustments to the search weighting to push low-rated stories down the search results – something we’ll be playing with in beta.

I think if users (writers and readers) start tagging other people’s content, it’ll work just fine. If not, we’ll have a platform working on a narrow-folksonomy model (writers tagging their own work on upload) which obviously can work well, and has lots of precedents, but isn’t what we hoped for. It’s really satisfying to read stories on there, and tag them jimsfavouritestories the search for that and have them all returned. I can use that functionality to make playlists for other people, or share with a group. If people get that, we’re in business.

Will Barrett: The work you’ve done on discoverability is really great…

Jim Hinks: Re: stars ratings. Yes, we tried a few variations at the prototype phase. I think a lot of this stuff is about building on existing user-behaviour. Most people have used amazon. Most people understand what a 5 star rating is. We’ve got enough new things to teach them.

Will Barrett: Star systems are surprisingly useful, even if it feels a bit wrong to condense a work of art down to such a crude measurement. I don’t have much time to spend searching for something, it’s a very handy shortcut if I need a hand blender and want to know which ones work the best. The ratings are reassuringly reliable.

(*Need* a hand blender.)

It’s a bit different with stories though, isn’t it? It’s much easier to agree on an objectively ‘5 star’ hand blender than it is on a story, which thrives on subjectivity.

Jim Hinks: Yes. But some people are REALLY into hand blenders. I have 4! But I agree about subjectivity. Anyway, the main reason for it on MacGuffin is to alert readers to bad audio. A text rating of 5 and an audio rating of 2 should tell you beforehand. You can also look in the analytics for that story and see whether other readers have dropped out before then end.

There’s a whole section to be added to analytics, about which tags are trending where in the world, and what stories are trending for each of these tags, and so on.

Will Barrett: The analytics side is very cool and I like how comprehensive it is, and that you’re sharing all that information. Kindle don’t do that. It democratises the insights you can get as writer from how people read your work (and where they stop reading!)

For a writer, analytics could be more useful than reviews. On Amazon I NEVER read reviews for books. It’s rarely helpful: “I didn’t like the film version of this book”, “I didn’t like the fact an elephant got shot, that was sad”, “the book is too heavy”.

Jim Hinks: Hey, we’ve come back to comments again! As a short story publisher, we sometimes get Amazon reviews saying ‘I wish this book had been a novel’. In a way that’s stupid, because they’re reviewing a collection of short stories, but at the same time I suppose it’s still valid, and I don’t doubt their sincerity in wishing it was a novel.

Here’s a classic. http://www.amazon.co.uk/product-reviews/1905583524/ref=cm_cr_dp_hist_two?ie=UTF8&filterBy=addTwoStar&showViewpoints=0. But again, you can’t really argue that it’s not a sincerely held opinion.

Will Barrett: Have you done any user profiling for Macguffin? On CAMPUS we’ve been using the Forrester model. So that defines users according to behavourial traits – Influences, Engagers, etc – and we use observation to monitor different groups.

Jim Hinks: Well to go back to the beginning, we started with a design jam. We basically invited a bunch of readers, writers and literature professionals (creative writing teachers, librarians, etc) to listen to the idea, decide on some functionality and tell us what they think. We used a lot of their input, and discarded some (like a facility to comment on stories, for reasons discussed above). We then prototyped. fffunction – the tech partner – are very good at UX, and they built a prototype that we guerrilla tested a lot, through several iterations. This was following several key predefined user-journeys, such as search for a story, upload a story, etc.

By January we had an alpha-build, on a live database (the first time I really breathed a sign of relief, that yes, the end-user tagging will work, at least from a tech point of view). We tested this in MMU’s digital labs (again on pre-defined user journeys), and used retina tracking to flag up some design and navigation pain points (essentially users being flumoxed about where to find buttons they need to click). I can really recommend this – there are some videos on the blog; http://macguffinblog.com/2015/03/06/pain-point-videos-from-the-platform-alpha-test/. We also tested an early iOS build in the lab.

Will Barrett: Labs and retina testing! How fancy. I’ve been using A3 pads and educated guesswork.

Jim Hinks: This gave us a whole list of bugs and UX issues to fix for the beta release (last week). We’re pretty happy with the beta, but it’s not the end of the story. We’ve built in a good couple of months to respond to beta feedback (and further functionality requests) before the launch proper at the end of June. In test of gathering data during the beta, I hope users will use the forum, but it can be more important to pat attention to what people do rather than say. Our own analytics, combined with Google analytics, gives us quite a lot of data on this. Forrester sounds good and the first thing I’ll do after this is check it out.

Will Barrett: ‘Forrester’ is just a model, and it’s a bit academic for my purposes, but have a look. It’s an interesting at how to segment different types of ‘groups’ in an online environment when you’re faced with a big morass of stuff that you can’t really make sense of.

Jim Hinks: I must say I was slightly skeptical about retina tracking beforehand, but now I’m a convert, having stood in a soundproofed control room watching people fail to spot a button that I thought was obvious.

Will Barrett: I’m very skeptical about all that stuff too, but it sounds like it was genuinely worthwhile for you.

Jim Hinks: We had users do a ‘think aloud’ as they tried to complete tasks, and I was surprised at how often what they say doesn’t correlate with what they do. No matter how much you tell them they’re not the ones being tested (if they get stuck, it’s a problem with the design of the platform), people still feel self-conscious and don’t want to look silly, so their think-aloud often tries to mitigate the problem, rather than elucidate. Eye-tracking reveals this. Dan Goodwin, UX lead a fffunction, is adamant that watching what people do comes way at the top of the list, followed by what they say, way down. The user-testing we did seems to bear this out (and I say all this with the caveat that the beta is still far from perfect – though I hope we’re getting there).

Will Barrett: That holds a lot of truth for my experience as well. When I’m doing diagnostics on technical issues, I rarely rely on testimony, as you’re exactly right – there’s a huge gap between what someone says they did and what they actually did. I don’t think they’re lying to me though!

What about the way the stories are displayed, which is done in a certain way, grey serif font, line spacing, there’s a fade effect as you scroll through. Where does decisions made out of UX testing?

Jim Hinks: The look of the text has gone through a few of iterations, but it’s been relatively easy to get something we’re happy with. Pete Coles, the visual design lead at fffunction, went through a range of fonts and styles with us. The hardest part is getting the formatting right on text upload (or rather, when writers copy and paste into the text field). People paste text in from a range of sources with different proprietary html tags (MS Word being the most egregious culprit). It’s still a headache.

Then we apply our stylesheet to it – so there’s uniformity to each story and poem. You can select ‘poetry formatting’ to remove indents. You can apply italics, header, align left, right and centre. And that’s it. There’s an accessibility reason for this, as well as an aesthetic reason – if writers use all kinds of wacky fonts, it makes it harder for visually disabled users.

Will Barrett: How have you dealt with the accessibility issue with MacGuffin? I learned a lot doing CAMPUS about how to define user-end responsibility, and issues that were our responsibility as site designers and developers. You can make things as easy as possible but human fallibility is a constant factor. But deciding which is which is tricky.

Will Barrett: There’s a big generation of very technically literate, and literary literate, young writers, really anyone up to about 40, who wouldn’t have a problem with Macguffin. And even the older ones tend to be fine, but they self-identify as technophobic and that blocks them from wanting to progress further.

Jim Hinks: YES – I completely agree with you. I’ve heard it quite a lot already: ‘that sounds too complicated for me’. But when I’ve cajoled them into trying it, most have been fine.

Will Barrett: Some messiness is always inherent, but you always hope natural order will prevail.

Jim Hinks: It’s sort of hard knowing what success is going to look like. Just proof of concept isn’t enough, but at the same time you need to be realistic. I do believe that if we can get some momentum, it will be a fun and useful tool for readers and writers. The best thing about working on it so far has been the moments when I’ve used it myself – on my commute or on a train journey – and lost myself in a story or poem, then thought, ‘yeah, actually, this thing’s pretty good!’ It’s not a case of ‘build it and they will come.’ Success will probably 75% about marketing and press

I think the ingredients of MacGuffin – audio, content discovery, self-publishing, analytics – will all play an ever-larger role in publishing in future (and therefore contemporary literature).

Will Barrett: What do you think the bigger long term potential for Macguffin is, particularly on the wider industry. You mentioned Arvon earlier. How do you think it’s going to fit into the literary ecosystem among the readers, writers, agents, schools, universities, reviews, media, festivals, fairs…

Jim Hinks: We drew up a list of all the reading and writing communities who might MacGuffin: published poets and short story writers promoting their books, aspiring writers finding a new audience, creative writing students and teachers, publishers showcasing work (you can link back to point of sale), reading commuters, spoken word performers and audiences, blind and visually impaired readers (who often only get access to audiobook versions of books by best-selling authors, not emerging authors), reading groups, writer-development agencies. We need to reach each of these groups through press, direct marketing, social media, etc., and make sure they know the proposition – what MacGuffin offers. Within each of these groups there are also of course genre divisions – we need to reach out to the SF writers, the crime writers, etc etc. That’s how you do it, I think. You hope for some really good, impactful press, but inevitably a lot of it is piecemeal. It’s a numbers game, and an absolutely endless job. I doubt there’ll be a moment when we can sit back and think we’ve cracked it. There’ll always be more to do.

*use MacGuffin*

Will Barrett: Ha! There was one question I should have asked earlier I’ll quickly drop in. It’s about copyright! Everyone’s favourite topic. What’s the position with original work published on Macguffin?

Jim Hinks: Writers retain copyright, and can publish under a variety of licenses: All Rights Reserved, one of a range of Creative Commons Licences, or release into the Public Domain if they wish. They have to agree to the Terms of Use when they sign up, and Content Rules when they publish, which include taking responsibility for the content and not infringing anyone else’s content. As much as I think DMCAs are imperfect, you can report content and request a take-down.

Will Barrett: Ok, so big final question – what does Comma Press get out of all this? Be as honest as you’re prepared to be…

Jim Hinks: I think the ingredients of MacGuffin – audio, content discovery, self-publishing, analytics – will all play an ever-larger role in publishing in future (and therefore contemporary literature). Strategically (*bleurgh*), it makes sense to try to be at the vanguard of innovating in these areas. I of course love hardcopy books – we’re a publishing house, after all. On the other hand, I get slightly exasperated by people who claim to love books, but not in a digital format. If the best thing your favourite book has going for it is the feel and smell of the pages, Literature is in trouble. At essence, MacGuffin is just experimenting with new ways of doing what publishing has always done – connecting writers with a readership.

Will Barrett: Cheers Jim. It’s been really nice chatting to you and have a good election night!

Jim Hinks: You too. Let’s wake up to a better England.

…

Appendix: after this conversation we did not wake up to a better England.