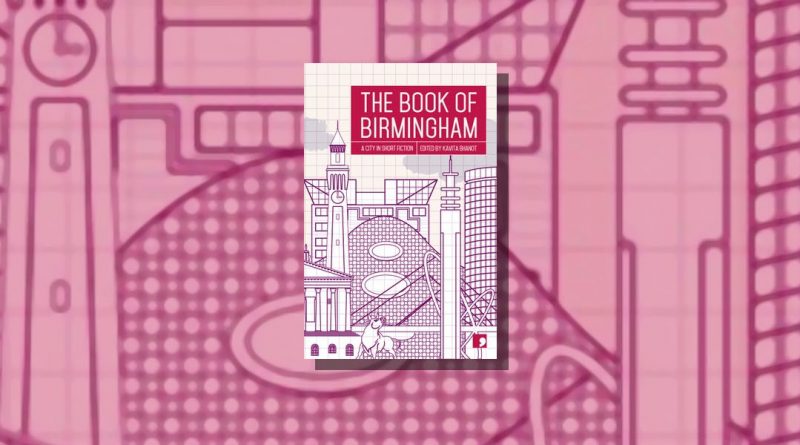

The Book of Birmingham edited by Kavita Bhanot

– Reviewed by Jenny Booth –

Although I don’t know Birmingham, the stories in The Book of Birmingham (Comma Press, 2018) speak to anyone who lives in a UK city. The chicken shops and hair shops of Soho Road reminded me of Radford Road in Nottingham where I used to live. The description of the ‘wasteland of garages, factories, scrap yards and expressways’ abandoned to white nationalism in ‘Blind Circles‘, Joel Lane’s atmospheric sci-fi story, felt grimly familiar. Headlines and news bulletins about urban riots and racial tensions have been a perennial feature of post war history.

The writing in this anthology takes the reader in behind the sensation and spectacle and demands proper attention for the lives of the people affected and involved. It takes the reader inside clusters of rooftops seen in snapshots from Digbeth, New Street, Spaghetti Junction, and shows neighbourhoods, families, dramas. The Book of Birmingham also made me question what it might mean to know any city. The answer it appears to offer is complex, requiring consideration of the fluid and contested boundaries between communities, individuals within those communities, architecture and memory. In ‘Necessary Bandages‘, C. D. Rose’s piece on the Birmingham Surrealists, he breaks into the narrative to reflect:

‘Half a life ago I lived in Birmingham; half a life later I came back. Time had been kind to the city, in its way: it seemed to have thickened and slowed to the point of near-stoppage, trudged on by a few minutes for each decade. And yet, builders had shifted their hands to tearing down that which they had not long completed. Birmingham is a true city of the future: endlessly becoming, never arriving.’

Racism and racial tension is a significant theme in The Book of Bimingham. ‘Exterior Paint‘, the opening story by Kit de Waal, is the story of Alfonse Maynard, a black migrant from St. Kitts and his recollections of meeting and courting Lillian, a white woman. Their story is set against the political realities of 1960’s Birmingham; the segregation that bars Alfonse from the lounge in the pub where Lillian works; the disapproval and racism of Lillian’s family. It dramatises Malcolm X’s visit to Smethwick in 1965.

The power of the story comes as it draws the characters of Alfonse and Lillian with skill and empathy. It demonstrates the importance of Malcolm X visiting the community by showing it through their eyes, showing it how it impacts on their lives and their way of seeing things.

A similar problem of love encountering racial division is found in Jendella Benson’s ‘Kindling‘, set against the 2005 violence in Handsworth between Black and Asian communities. Lauren, a teenage girl, is trying to meet up with Zee, a teenage boy she met on the bus. The obstacle to this is potential prohibition or violence, from police controlling the streets, and a group of black teenagers who disapprove of Lauren, a black girl, being with Zee, who comes from a South Asian community. A greater obstacle is their own learned prejudices towards the other’s community. The language Benson uses is important and revealing. Teenagers saying ‘orite’ and ‘ennit’ are used too often by middle class satirists, as a shorthand for teens being stupid or insensitive, or worse, as an endpoint, that this language tells you all that a reader needs to know about a character. In ‘Kindling’ it’s a starting point. Benson reveals Lauren and Zee as dignified and thoughtful people when she shows how they’re affected and shamed by the degrading cliches they’ve been taught to use against each other, and when they choose to challenge them.

There are similar things at work in Balvinder Banga’s ‘1985‘, set during the Handsworth riots 20 years earlier. The narrator and his cousin Ash come from Punjabi Sikh families. They try drugs and alcohol, they try to pose like Al Pacino and Marvin Hagler, they care about their families and each other. They are, in other words, fairly typical young people. The difference for Ash and his cousin—and for Lauren and Zee—is the potentially devastating consequences of making a mistake as they try out aspects of adulthood against a background of violence. That these teenagers face such hostile circumstances is tragic; that they appear to overcome them is humbling.

Although many of the stories in the anthology are political in some sense, they centre on the human and the poetic.

Sharon Duggal’s ‘Seep‘ beautifully uses the point of view of Bina, a teenager who arrived in Birmingham from the Punjab as a child, her observations of family life, soul music and adolescent sexuality, to explore the pull of different cultures. C. D. Rose uses a grotesque and surreal approach to approach the Birmingham Surrealists, a group of people committed to imagining and creating different realities through art, and how these possibilities have been to some extent curtailed by the nature of urban development in Birmingham.

A more modern group of Birmingham creatives, The Tindal Street Fiction Group, is showcased in the collection. Four of the authors, plus the editor Khavita Bhanot, are or have been members of the group, whose aims include challenging London’s dominance in writing and publishing. Alan Beard’s collection, ‘Taking Doreen out of the Sky‘ was the first book published by their press; the eponymous story appears in this collection. It’s a story about the closure of a factory that manages to be funny, empathetic and evocative.

‘I tiptoed in and bent to kiss the dark sweat-smudged curls, a baby taste still, strange in the coloured darkness. A pure, warm taste, not wrecked yet like adults were with stuff, drink, drugs, dirt.

It came to me in that room, my eyes gradually picking out toys and story-books and cartoon wallpaper, it came to me that our marriage was like that: in its infancy, not wrecked yet. Whatever might happen, it was not wrecked yet.’

The Book of Birmingham is a fantastic collection of short stories that doesn’t put a foot wrong. The human perceptions it offers into the politics of race in Britain are of great importance, particularly in the recent contexts of Windrush and the endless dehumanising debates around migration. It provides a window onto Birmingham, an insight into what life in tower blocks, notorious estates, even the ghosts of long demolished houses is really like; and more generally, on the possibilities of art, and the beauty and poetry to be found in everyday life.

—

On Saturday 18 May 2019, Birmingham plays host to the annual Saboteur Awards for the first time.

- View the Saboteur Awards 2019 shortlists

- Book tickets for Saboteur Awards Festival daytime and evening events

—