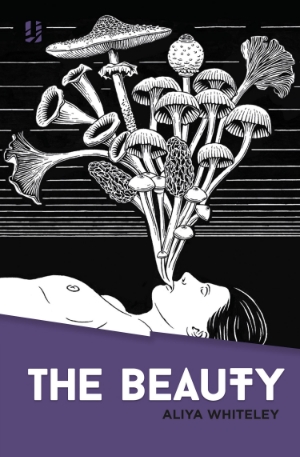

The Beauty by Aliya Whiteley

-Reviewed by Richard T. Watson–

The Beauty opens with an intriguing idea: a near-future world where all the women have died.

This might sound like it makes for a masculine novel, full of men being real men and doing manly things – whatever that means. But actually, the core of this novella is very much a question of what constitutes femininity, and what women contribute to a society. There’s a bit of male posturing, sure, but ultimately, this is much more about people and complementary genders than it is about testosterone.

‘I was sixteen when they all died and I thought I understood this loss, but it comes to me that I didn’t know what women gave to the world. It wasn’t about their lips, their eyes or the gentle quality of their voices. It was about the way that all men are a part of them. And now we are part of nothing.’

It’s not uncommon for science fiction writers – especially women – to present a world of women, whether that’s matriarchal societies or worlds where the men have disappeared. It’s an opportunity to explore femininity and female society (and any other topic) without the interference or restriction of men and the patriarchy. By contrast, Aliya Whiteley’s The Beauty explores the contribution of women to a society by removing them and examining the gaps that are left.

So we begin with a small group of male survivors, living in the middle of nowhere and having to take on the more traditionally female roles for themselves. They don’t seem to mind too much, but there’s a keen sense of loss and of something missing, even though several of their number are too young to really remember the time before the women died.

To begin with, the loss is maternal – men don’t tend to bring the same sense of comfort to each other – and it’s through that loss that the Beauty first approach Whiteley’s narrator. He is absorbed into the warm, damp earth, with its hints of a womb-like nature, drifting into unconsciousness to the sound of ‘the mother-hum’ of the earth. His first encounter with one of the entities – for want of a word better than creature – that he names the Beauty, comes after a metaphorical rebirth into an underground chamber, where for the first time he feels at peace.

It’s no coincidence that the Beauty spring from a proverbial Mother Earth, or that they are initially and frequently associated with the mushrooms growing from the graves of the dead women. The description of their yellowy, spongy skin and a ‘smooth, round ball for a head’ marks them as somehow fungal – part of neither the animal nor the plant kingdoms – despite their limbs, breasts and ’rounded hips that speak to me of woman’. Their fungal nature ties them intimately to a cycle of death and rebirth, none more so than when their means of reproduction becomes apparent and they offer a new hope to the continued survival of the human colony (though not, perhaps, in the usual human form). The novella’s opening, before the Beauty are discovered, is full of signs of new life, contrasted with the relative barren future of the all-male survivors’ group.

In the shadows, of course, around the nightly campfire, the loss of women is also felt on a sexual level, but the younger men are able to bring some comfort to each other there. It isn’t long before the Beauty offer their comfort on that front too, and become integral to the emotional wellbeing of the men.

I say there’s a lack of female characters, and, strictly speaking, I think that’s true. But it perhaps overlooks the Beauty themselves, who grow from the remains of the dead women and, to some extent, take the women’s places in the new society. They remind the men of what they’re missing, arousing a whole bunch of feelings they’ve been keeping repressed. When the narrator first encounters one, he’s drawn to her hands:

‘They look delicate, decorative. They are not hands hardened by work. To look at them makes me feel jealous, desirous and protective, all at the same time. Such little hands. If I look only at the hands I feel warmth spreading through me. They are feminine. I haven’t seen anything that fits that word for such a long time.’

It’s such a male reaction, and is the beginning of an acceptance, that eventually spreads – more or less – to the rest of the men. With the men paired up with a Beauty each, their little society approaches some sort of happier stasis, less threatened and dystopian than before the Beauty came. It’s a new start for humanity, born out of the death of the women, and both groups seem to feel more content and complete.

There’s something of Neverland’s Lost Boys here, yearning for a mother-figure they don’t necessarily realise they miss. Like the Lost Boys, Whiteley’s men sometimes react with violence to things they don’t understand, or that scare them. These Lost Boys are teenagers and grown men, not children, so they want more than a mother, and their desire is also a complicating factor in their disgust. Of course, unlike in Neverland, that violence contains the seeds of eventual destruction, and perhaps that’s the big difference between Whiteley’s world and J. M. Barrie’s: Whiteley’s has much more grown-up pain, desire and darkness.

The idea of an all-male world might not be new, but Whiteley’s angle here isn’t so much about what the exclusively-male society has, so much as what they’re missing, and what they’ve lost. What’s under examination here isn’t how men interact, but how mixed-gender groups complement each other. This happens because of, rather than despite, the lack of female characters.

Science-fiction is a space to play with ideas, and to let them run to their conclusions. Whiteley has given her idea plenty of room to run and run, and the result is engaging and thought-provoking science-fiction.