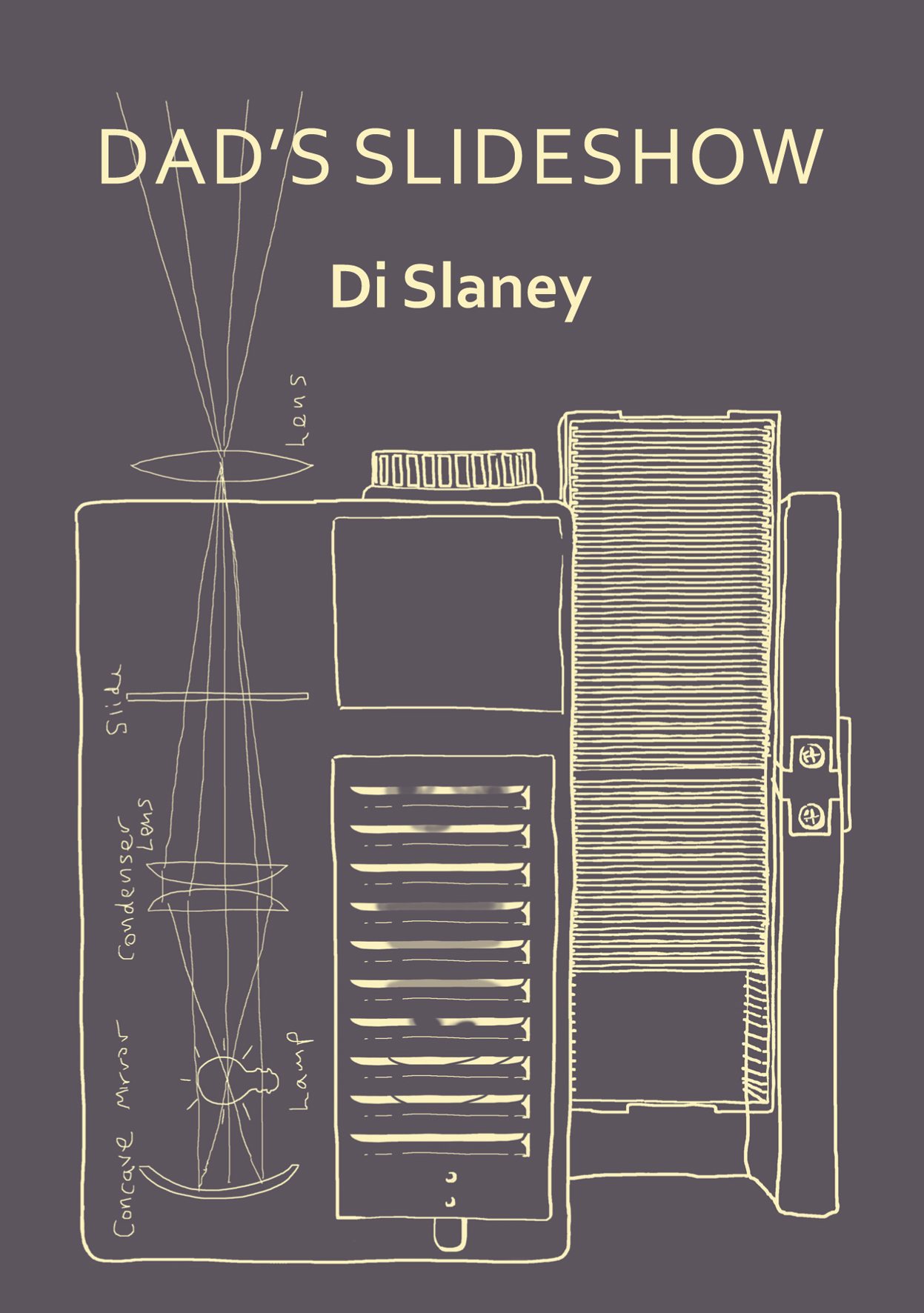

Dad’s Slideshow by Di Slaney

– Reviewed by Rachel Stirling –

Dad’s Slideshow is a small brown book which could easily be mistaken for an instruction guide to a camera or projector, yet folded inside, instead of specifications and indecipherable text, we find a journey along the timeline of a particular family. The poet darts back and forth between voices, perspectives. Sometimes we hear the voice of the eponymous father, sometimes the voice of his child or the the antiphony of siblings. She explores the nature of family and what it means to belong: what do we pass on in our genes and what do we learn simply by being together? Everywhere throughout the collection we meet the idea of attention, and the question of whether we equate it with love. This is a book in retrospect, multiple voices singing the same song, the song of family. Memories and the story of memories, the faith and fable of a shared history. The tone is both conversational and confessional, yet a questioning thread of darkness runs through it.

It’s easy to relate to Slaney’s snapshots of family holidays and sibling rivalries. The language is open and welcoming and the word choices deceptively simple, apart from a unique flash of dialect in West of Dolgellau. Closer inspection reveals that the simplicity and directness of the voice is a melody line dancing over a complex and cajoling mastery of form: the mind skips over it almost without noticing. The poet gives us a firm foundation and we are never left to feel insecure. It’s no accident that there are only a few words of Welsh used in the collection, and they translate as Good Night and Go Home, underlining the sadness of a past which can no longer be revisited, an ending.

Slaney is no stranger to enjambment, creating glorious repetitions across stanzas. It takes a deft hand to place consecutive rhyming couplets without an overwhelming effect: here they are placed with such assurance I barely notice them for what they are. There are also quatrains with a beautiful 2-1 4-3 repetition across the stanzas, a little dance or fugue, and it is a credit to the delicacy of the poet that I have to search them out.

An element of imaginative ventriloquism emerges in some of the writing: Slaney places words in the mouth of the father in particular, re-evaluating. The young child has now grown, and is reassessing relationships between family members in the light of her maturity. There is a refreshing honesty in this, along with a repetition across the collection of ‘I don’t know,’ which leads to the understanding that, of course, we never know; we make guesses, educated guesses, about the thoughts and feelings of those whose lives we share and those who came before us; it’s all we have. I think the touch of melancholy through the writing is best reflected in the lines

Did you see me then, Daddy?

Do you see me now?

There is sadness in the insecurity which leads to this question. Moving through the particular to the general, does anyone truly see the truth of us? Can we be certain that even we see the truth of ourselves, or is our view coloured by expectations, remembrances and similarities, the many repeated faces of family?

However, I have to end on a happy note: many joyful, childhood memories came back to me on reading this pamphlet, not least the memory of sitting, bareback, as the poem states, on the broad, table-top back of the coalman’s horse, fingers wrapped in his mane and legs at an improbable angle. We were both three.