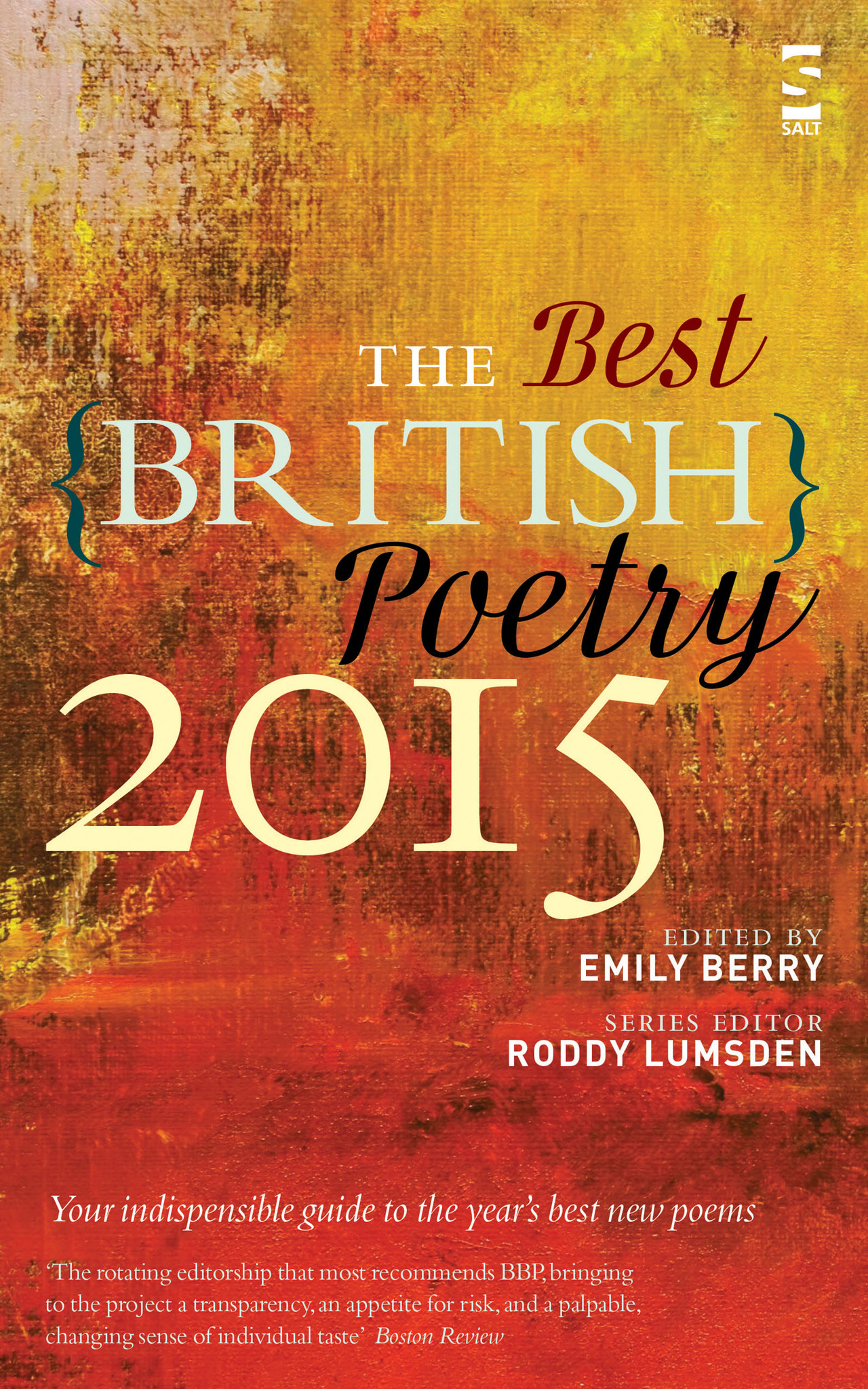

Best British Poetry 2015 edited by Emily Berry

– Reviewed by Jenna Clake –

In her introduction to Best British Poetry 2015, Emily Berry states that when she was selecting poems for the anthology, she ‘thought dutifully about the meaning of “best”’: whether or not she should choose poems she liked best, or poems ‘deemed, somehow, objectively best’. Luckily, she went with the former, resultingin an anthology which takes us on a tour of Berry’s bookshelves (or what we can imagine is there).

Women’s poems appear most frequently and Berry admits that this was an opportunity to tackle the imbalance of gender in poetry: In an interview with The London Magazine, Berry says that she ‘wanted to ensure the anthology was more than 50% women because [she] wanted to redress the balance in a small way,’ though she admits that ‘this wasn’t something [she] really had to make an effort to do, because that’s already [her] frame of reference.’ The first five poems in BBP are by women, and the first two are a riposte to gender inequality.

Aria Aber recounts, in a poem (‘First Generation Immigrant Child’) about how her father wished ‘the Americans or Brits/ had colonised our country’, how the Taliban treated her mother:

the Taliban tortured my mother for being

a feminist, she had to stand for thirty-three days, tongue-dead

and freezing, until her period crawled down her thighs.

The humiliation is tangible in this poem; we are told that ‘blood is thicker than water, / even for whores,’ and it becomes apparent that blood – perhaps specifically menstrual blood – is seen as the source of women’s shame.

Astrid Alben takes a more humorous approach in her poem ‘One of the Guys’, in which a poet tells her ‘how not too much poetry / should be done by too many girls.’ The drunken slurring of the poet is one of the highlights of the poem: ‘Are you turning, shurely not, feminissshht?’ Alben’s poem surely resonates with many feminist readers and poets, and the comedic timing ensures that we feel as though we are being told this story over a drink, and can laugh at the poet too.

Rachael Allen’s ‘Prawns of Joe’, inspired by Selima Hill’s ‘Prawns de Jo’, is not ostensibly addressing feminism, but Allen’s accompanying note suggeststhat, as a woman, ‘feelings of shame are mandatory’. Hill’s poem allowed Allen to explore her own feelings of shame through a portrait of a claustrophobic relationship, and the humiliation that pervades when it ends:

When I had a husband I found it hard to breathe.

[…]

In amongst all the crying, I see

a burning child on the stove.

The same one as before?

The curtains are full of soot.[…]

There’s a woman over the road

who moved in after he left.

She has a black little finger

and has been watching me for days.

Claustrophobia also pervades Kit Buchan’s ‘The Man Whom I Bitterly Hate’. Buchan’s use of rhyming couplets makes the recurring appearance of the man inevitable. The bizarre nature of this episode seems to be inspired by Luke Kennard’s poetry:

I leave in the evening and waiting for me is a man whom I bitterly hate.

He’s staring at me with improbable glee and I gulp as his pupils inflate.[…]

Then after he’s kissed me he buries a fist in my belly to tell me I’m late

and with each cigarette that I take I forget he’s the man that I bitterly hate.

A short selection of Luke Kennard’s anagrams of Genesis 4: 9-13, from his recent collection, Cain, also appear in BBP. In Cain, the anagrams are given context in the form of marginal notes that create a box around the anagram (they are the episodes of a sitcom featuring Cain, Father K [a version of Kennard], and Adah). The anagrams appear alone in BBP, but the reader will still manage to understand what is happening. The anagrams show how Kennard has creatively dealt with some of the challenges posed by Genesis 4: 9-13, such as its use of the letter ‘H’ forty-one times:

We enrol at HRH Ethelred University at Adah’s behest. Cain has taken

10 evening modules:

Arsehole Theory

Misunderstanding 101

Heartburn Studies

The Novelette

Troubleshooting the Mithridatised

The Modern Underachiever

Draw in H, 2H, 3H, 4H, 5H, 6H, 7H, 8H, & 9H (& Rub)

Footnote Clutter

NSFW

Berry seems fond of sequences: many of the poems selected are sequential, challenging the typical ‘poem’ form. Jesse Darling’s ‘14 Dreams’ recounts, in prose poem form, fourteen dreams which become stranger and more disturbing:

A young girl becomes pathologically fixated on some dark magical aspect of sex; it begins with her own lover, who then disappears, and after that she wants mine. My love is a man and I’m not really me either. She’s in the hallway outside our room, breathing hard and turning herself inside out.

Darling is able to capture the terrifying, disorientating nature of a dream, and also the ease with which we find ourselves immersed in a new world – ‘14 Dreams’ feels like it should never end.

Sophie Mayer blurs the lines between poem and essay in ‘Silence, Singing’, in which she discusses the voices of women:

These are the words I was given.

Be a good daughter

Lead a good life.

Find a good husband.

Be a good wife.[…]

In my matching Artscroll siddur, I could have found this short prayer said daily: ‘Blessed are you, Lord our God, Ruler of the Universe, who has not made me a woman.’

Mayer moves away from the biographical to consider women’s writing:

As Anne Carson argues in her essay ‘The Gender of Sound’, no-one likes to hear a woman’s ‘vehment cryeng’ – which is often how women’s writing is heard. Confessional, over-emotional, nonsensical, hysterical.

Throughout, Mayer moves from her own experience to how women have been received and perceived in literature, discussing Thomas Wyatt’s translations, and Iphigenia in Euripides’s plays. She discusses the idea of giving a voice to Iphigenia, even after her death:

There is no unwriting Iphigenia’s death. But there is writing it: borrowing it, not to shore up the security of the status quo, but to graffiti the walls. Not to uphold the law, but to break it.

The idea of giving a voice to the unheard is prevalent in Alex MacDonald’s ‘End Space’:

I have been asked to write

in a room like this you think of the hiding places first

secret drawers dusty chairs behind metal shutters there is a smell

of medicine in the air but I do not look sick I look great

The speaker recounts, in snapshots of insignificant details, their day and routine. At times, the oppressive nature of their existence is evident:

I found the tennis courts

the rackets lined up like machine guns[…]

who is watering my plants at home? My brain feels dirty

as if it has grown a beard I want to wake up very early to see how

the days changes so I could say to someone ‘well, it was much nice earlier’

but I feel slow I haven’t seen anyone for a while

I feel a sort of sympathy, but also alienation from this speaker. There is a sense throughout that we might never quite understand what has happened to them, or why they think this way, and this sadness pervades MacDonald’s poem.

There are many, many more poems that could be and should be discussed. Berry has certainly done an excellent job of selecting some of the ‘best’ poems of 2015, as the anthology isn’t simply fulfilling one criteria: this isn’t a feminist anthology, although there are feminist poems; this isn’t an anthology for women, although the majority of poems are written by women; this isn’t an anthology of surrealism, although there are plenty of surreal or absurd poems. Berry has put together a varied, sad, disturbing, exciting and humorous collection.