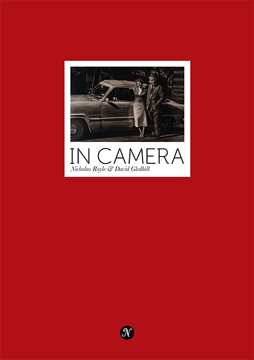

In Camera by Nicholas Royle & David Gledhill

-Reviewed by Adrian Slatcher–

In Camera follows on from other books from Roelof Bakker’s Negative Press in being both uncategorisable, and at the same time recognisably from the imprint. This seems to be what small presses should be about. In Bakker’s case, each project connects up photography with text in new and surprising ways.

The stylish In Camera came about from the work of the painter David Gledhill, who discovered a book of family photographs at a fleamarket in Germany, depicting the old East Germany. In his studio at Rogue Studios in Manchester I’ve seen in the flesh some of Gledhill’s photo realist paintings that are reproduced here. The transformation between mediums adds something to the source material: they are imitations but they are also impressions.

This book adds a new layer to such interpretation, where Nicholas Royle uses the pictures to provide the inspiration for a short story, which here is interpolated between the various pictures. Each picture becoming a scene from a story; an imagined story of a doctor in the DDR, whose family becomes a target for the Stasi. In one scene, where the lead character is looking back trying to understand what happened in her childhood, her friend P says ‘one in twenty doctors in the DDR…spied on their colleagues and painters,’ twice the amount of collaborators in the general population. A doctor has access to privileged information, also, for the authorities, their transferable skills meant they were seen as more likely to defect to the West.

But the story here only slowly comes into that reflective present. It begins with an every day incident in the surgery, where the narrator’s father is treating a patient who slipped in the street. A child becoming dimly aware of their relative privilege compared to their neighbours, she suspects her friend J. has been responsible for the banana peel that the patient injured himself on. In the second short scene, she finds that her father has taken up photography and occasionally leaves the camera in a place where she is able to ‘borrow’ it for a few minutes.

We know that where there is a set of photographs there must also have been a camera which was used to take them. In those days, the care taken to ensure each picture was worthwhile, because of the cost and time it took to get photographs printed, meant that each photograph in an album would have significance. Royle imagines not just what’s in the photographs, but the ‘unseen’ story behind their taking. In every photograph of a person there’s the unseen camera operator. Who might it have been? At times it’s the daughter, at other times maybe it’s G, the untrustworthy son of ‘Onkel F’. He’s not a real uncle, of course, but as the story unfolds, we get hints at who he might have been – the person who tried to recruit the doctor as an informer, and when he refuses, the person who spies on them.

Told through the twin fractures of a child’s memories, and the prompts of these photographs, the story is a remarkably satisfying one, full of hints and half truths. This ‘real’ family is brought to life – or rather, the pictures are an inspiration for an imagined story that can have an authorial significance, unconstrained by whatever the true story told by the photographs might be. Taking a picture and imagining what is the story behind these lives. It’s what historians have done for decades, yet here is something in living memory – memorably told in Anna Funder’s Stasiland – that is well documented but has a whole layer of secrecy behind it.

In this short story that because of its accompanying images, repays re-reading and exploring, Gledhill’s pictures provides a constrained landscape against which Royle has created a carefully crafted story of 1950s East Germany. The style is pared down, and reads as if it might almost be in translation. It particularly reminds me of Natalie Ginzburg’s The Things We Used to Say where a child’s view on the everyday is used effectively to uncover the horrors of the age, in her case, the rise of fascism in Germany, in Royle’s case, the anxiety of the East German surveillance state. Royle’s doctor is the hero of this piece – ‘he protected us, and he protected his patients…anyway, it’s all history now.’

These photographs, these paintings, this story provide a plausible version of that history – and the books, like previous Negative Press offerings, is a beautiful presentation of the project it contains. Highly recommended.