Currently & Emotion ed. by Sophie Collins

-Reviewed by Jenna Clake–

Translation is a political act: this is the recurring message behind Currently & Emotion. In her introduction, editor Sophie Collins notes that:

Shifting our perception of translation from that of a kind of literary service that simply facilitates access to foreign and/ or historical texts, to one that recognises an influential, political and manipulative act, is vital, because when ‘representation’ is viewed as something unproblematic, capable of providing ‘direct, unmediated access to a transparent reality’ … translation does nothing but reinforce hegemonic versions of the colonised, presenting individuals as ‘objects without history.’

The aim of the anthology not only exposes the political elements of translation, but also challenges the perception of translations ‘being either “faithful” translations that reproduce inasmuch as is possible the source text’ or ‘“free adaptations” or “versions” often rendered by poets with no initial knowledge of the source language.’ Collins outlines three types of translation as given by Roman Jakobson in ‘On Linguistic Aspects of Translation’: the interlingual (shown by ∞), which covers any translation of a text from one language into another; the intralingual (shown by ≠), which we can refer to as ‘English-to-English translations’; and the intersemiotic (shown by §), translations that ‘operate between different mediums’. The symbols are used to introduce each poet’s work, alongside a brief outline from Collins.

This approach is essential in making a reader (particularly one unaware of current discussions about translation) re-evaluate their views, and preparing them for the varied approaches to translation in the anthology.

The political is central to many of the texts in the anthology. Don Mee Choi’s The Morning News is Exciting is described by Collins as ‘completely political but not didactic’. Mee Choi herself states that ‘primary technique for translation and my own poetry is failure’. ‘Weaver in Exile’ is based on the ‘Korean folktale “Kyo nu wa jiknyo” or “Herder and Weaver”. The story concerns the romance of the female weaver and the male cowherd whose love for each other is disallowed.’

Stars are whores.

I weave pubic hair for dolls and frogs naively lit by your orange lamps. If

cloth is meat, what is blood? Try weaving shredded wrists, decapitated

hearts. Was my mother a sacred bitch?[…]

Let’s skip to your dream. How many lamps did you see? Do you remember

east and west? Explain the island. Why is the bridge flat? Describe the

distance

between the murmuring pines. Did you love my mother? Will I remarry?

Mee Choi’s poem seems to be littered with non-sequiturs and dreams, creating a very disorientating poem (we might even call it Absurdist). The poem is addressed to the weaver’s father, and the speaker’s anger is tangible: calling the stars ‘whores’ and her mother ‘a sacred bitch’ suggests that the speaker is lashing out. The misogynistic language seems at odds with Mee Choi’s aims, but we can see the language as a reflection of the father’s views: the speaker uses the language to reflect how unfairly she is being treated.

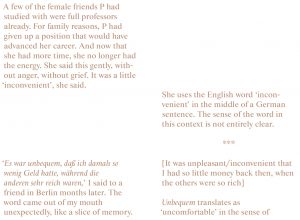

The mixture of languages is essential to Chantal Wright’s translation of Yoko Tawada’s German-language story ‘Porträt einer Zunge’, which layers footnotes and the translations side-by-side to create an episodic story of the speaker’s friend, P:

This poem consists of small, poignant and devastating moments, showing the ways in which translation might be impossible: throughout, words are not fully translated, or require substantial explanation so that we might understand. This, of course, is a commentary not only on translation, but how difficult it is for a person to live in a new country, and how difficult it is to adopt a language that doesn’t feel like your own.

There are also less conventional methods of translation: Collins takes ekphrasis as a translation and, furthermore, takes Rachael Allen’s use of the 4chan forums as an atypical form of ekphrasis. Allen ‘decontextualizes the visual materials on the 4chan boards, selecting images that correspond with adolescent experiences… and reappropriates them as unlikely emblems of girlhood.’ In ‘Animu & Mango’, Allen uses anime to write about a teenage love:

The main bit’s where Naru and Keitaro kiss and, in char-

acter, Keitaro and Declan who lived in Pensilva and had a

cast and wore school uniform even after school (poor) and

I was Naru. In one scene I made Declan promise we’d go

away to college together but I don’t think he understood, we

were far beyond the slap-pink and heavy breathing of a slow

Chinese burn but would carry on doing them in silence or

burn shag bands on hay bales that were shrink wrapped in

the nearly-dark and as he burnt grass I dreamt heavily and

cleanly about our future together it was in truth a sluggish

start anyway he’s in the navy now and probably knows how

to make a promise

Allen uses a conversational tone to capture a teenager’s voice; we get the feeling that we enter mid-conversation, and that anime and the real world are closely intertwined for this speaker.

No anthology of translation would be complete without including Anne Carson’s work. Collins includes ‘The Albertine Workout’, which takes Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu as its source. Collins notes that Carson seeks to ‘work out’ Albertine ‘as though she were a logic problem’:

8.

The problems of Albertine are (from the narrator’s point of view)

a) lying

b) lesbianism

and (from Albertine’s point of view)

a) being imprisoned in the narrator’s house.9.

Her bad taste in music, although several times remarked on, is not a problem.10.

Albertine does not call the narrator by his name anywhere in the novel. Nor does

anyone else. The narrator hints that his first name might be the same first name

as that of the author of the novel, i.e. Marcel. Let’s got with that.11.

Albertine denies she is a lesbian when Marcel questions her.12.

Her friends are all lesbians.13.

Her denials fascinate him.

The matter of fact way that Carson deals with Albertine certainly imitates someone working out a problem. This is a logical progression through a riddle.

Currently & Emotion offers many varied examples of how translation is being used in poetry to create exciting new work. The political issues behind translation are not resolved, but Collins’s attention to female poets and translators is important: her introduction hints at ‘rapidly occurring and measurable changes in attitudes towards race, gender, and modes of representation’ – it is a well-known fact that women are published less often that men, and Collins’s introduction points to the infrequent publishing of translations: ‘in the UK and US translations into English from other languages currently represent approximately 3% of all books published, and if we reduce this to literary fiction and poetry the figure is actually closer to something like 0.7%.’ It is therefore evident that Currently & Emotion is important: if translations and women’s work are published so infrequently, anthologies like this are a chance for work to be shared more widely.