May Utang by Jules Orcullo (Are We Where We Are?, Shop Front Theatre, Coventry, 11 May 2017)

reviewed by Stella Backhouse

Are We Where We Are? is a series of nine performance pieces to be premièred at Coventry’s Theatre Absolute over the next two years. Inspired by Henry Thoreau’s questioning of the consumerist and materialist obsessions of Western society in his 1854 book Walden: A Life In The Woods, Are We Where We Are? aims to draw on a range of theatrical approaches and personal experiences to explore the complexities of justice, equality, race, citizenship, nationhood, isolation, and inclusion that have come to define our experience of twenty-first century life. Are we where we are? Or are we somewhere else?

Opening the series at Shop Front Theatre on 11 May, May Utang, written and performed by Jules Orcullo, approaches the question of situation and belonging from a number of different angles. Roughly translated from Tagalog as ‘debt of gratitude’ and intercut with snatches of recorded conversations between herself and her parents, Orcullo’s new work mingles meditations on growing up as the fanatically Anglophile Sydney-born daughter of Filipino migrants, with rapid-fire reckoning of how much her education has cost mum and dad in cold hard cash (a lot).

For a second-generation non-white migrant to a black country with a majority white population (Orcullo is clear that Australia is, in her words, “a black country”), the provocation ‘are we where we are?’ inevitably triggers a complex and multi-layered response. Orcullo structures her performance around unpacking a series of unflattering stereotypical commonplaces about Australians (they’re racist, they’re sex-mad and the only work they’re interested in is bar-tending) and comparing them with her own experiences. The repeated phrase “the country we know of as Australia…” tolls through the work like a bell.

Reflecting these thoughts onto what appeared to be a majority white British audience adds to Orcullo’s story yet more dimensions. Australia, after all, began its modern history as a place for Britain to send the people it didn’t want; and as the work of Margaret Humphreys and the Child Migrant Trust has laid bare, Britain was still, to its shame, transporting children it didn’t want as late as the 1960s. (Australia did want them – but primarily so it could grow them into a ‘white defence’ against an imagined threat from South-East Asian peoples who look like Orcullo.)

Thanks to this complicated history, Orcullo’s narrative constantly challenges us to identify not only the ‘we’ in the “the country we know of as Australia”, but also those who ‘know of’ the stereotypes that seem to have dominated Orcullo’s relationship to her home nation. Are they white Britons, making uneasy sport of a country they characterise as populated mostly by the descendants of people they rejected (or who rejected them)? Are they white Australians, sheepishly colluding in the game? Are they anyone who is not Australian Aboriginal? And in her use the first person plural, is Orcullo aligning herself with the ‘knowers’ even as she disassociates herself from them?

In a sense, it is Britain’s own ambivalent and characteristically snobbish relationship with Australia that is reflected in Orcullo’s deeply personal experiences as recounted in May Utang. Some of the most searing passages in this searingly honest work concern the racism she has been subjected to not in Australia but in Britain. So while we no longer send Australia the people we don’t want, we are still, perhaps, prepared to attribute to them certain attitudes that we are less prepared to acknowledge in ourselves. In this reading, we are definitely not where we think we are.

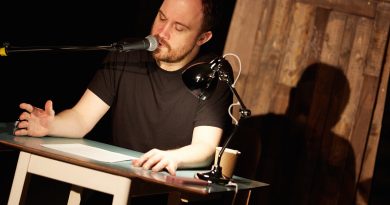

Orcullo is a clever and engaging performer: by turns funny, shocking and linguistically playful. Despite everything, the love and gratitude she feels towards both Australia and her parents shines bright. Whether the two strands should have been put together in a single work is perhaps debatable; there were moments when it seemed to lack clarity. The final impassioned plea for Aboriginal rights, though heartfelt, also felt slightly ‘tacked on’.

In a period when mass-migration is profoundly impacting Western political discourse and the Bank of Mum and Dad has been confirmed as Britain’s ninth largest mortgage lender, May Utang is both timely and urgent. But this is a work that, for all its present-day relevance is itself indebted, gratefully or otherwise, to the past – specifically to the colonial past of Britain, Australia and also the Philippines – and its continuing echoes through our lives today.

Image by Andrew Moore