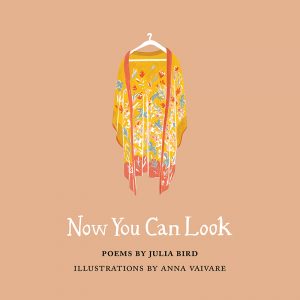

Now You Can Look by Julia Bird & Anna Vaivare

– Reviewed by Edward Ferrari –

Winners of the Publishers’ Award at the Michael Marks Awards for Poetry Pamphlets 2016, The Emma Press is a true believer in the power of the pamphlet, and it shows. Now You Can Look is an almost perfect fusion of form and content. Julia Bird’s vivacious poetry and Anna Vaivare’s energizing illustrations are testament to the faith, dedicated craftsmanship and superlative editorial work that this small press brings to bear on all its projects. Readers should expect socially astute, observational lyric poetry paired with unique, full page comicbookesque gouache and watercolour illustrations. Lucy Bourton has described Vaivare’s work as “full of energy and enjoyment”, making inspired use of “repetitiveness to display delicious textures”, and her bold and rhythmic style powerfully accentuates Bird’s writing.

In ‘The Artist in a Field in November’, Bird’s curt verbal parallelism suggests the collapse of a relationship, as “the wood catches, the crowd watches, / their colours wheeling round the blaze” and we are implored to “Look, […] when the bang comes,” at how “a husband whips his head towards the friend”. Vaivare’s illustrations offer thematically repeated patterns, like a William Morris wallpaper design, rather than competing narratively with Bird’s poetry. This works well. For ‘The Artist in a Field’, Vaivare creates an intricate background of black branches with perpendicular grid lines, foregrounding a collage of objects including robins, teddy bears, and a gas mask. This creates a surreal and mesmerising effect, as poem and illustration mutually reinforce their escape from convention.

The writing is consistently focused and evocative, hardly a surprise for readers familiar with Bird’s characteristically whip-smart, audience-conscious lyric. Here’s ‘She Makes Omelettes at 1 p.m. on a Sunday’ in full:

She is in the kitchen, cooking.

–––––––He is in the attic, painting.Rapt, he must be unaware

–––––––of the three globed yolks in her mixing bowland the fourth one, ruptured on the flag floor,

–––––––its split yellow and its blood spot.

From its fairytale opening, through its domestic imagery, to the final verbal pivot of “ruptured on the flag floor,” Bird’s poem manages to perform the linguistic equivalent of a one-two-punch. On the face of it these are domestic, familiar textures, but very quickly, as in Vaivare’s accompanying illustration, one notices the ants crawling in the wine glass and the knives and cigarette butts noosed by a looping rope. The darker depths suggested by both Bird and Vaivare give this pamphlet emotional clout.

A multilayered collection that plays with genre in interesting ways, Now You Can Look also contains several poems that adopt a more playful, experimental approach to their presence on the page. ‘We Leaf Through Her Sketchbook …’ and ‘A Bomb Damage Report’ make use of the 8×10 “big and beautiful” format that the ‘Art Square’ series provides. The latter, ‘A Bomb’, splits the poem in two, with a left- and right-aligned column of text facing each other across the page. This neat mimesis is thought provoking, as the reader becomes aware of their saccades across each enjambment, spanning the blank space between “one block / lost. 29A-29D / like a tin can shot / from the top of a / wall.”

The two page spread of ‘We Leaf Through Her Sketchbook …’ also makes effective use of the extra space afforded by the form. Its dispersed tercets suggest multiple trajectories across the page, interacting with the theme of the poem in productive ways. The “studies of sheepless hills / done in a spectrum of snow” not only connect to the painterly sensibilities of book as a whole, but run parallel to its attention to the materiality of print. The “last pages are blank // though this green mark is dock sap .. and this pressed flower, flax.”

Now You Can Look is almost perfect, but several of the poems feel a little hemmed in: ‘The Assistant Escorts’ and ‘Without Confiding in a Soul’ only just negotiate the margins of their pages. This is the only point at which I feel the form of the book impinge on the reading of the poems, and it hardly detracts at all, but a more minimalist approach might benefit the reading experience in future editions.

On the whole though, Now You Can Look is an energetic, vibrant work of literary art generated by a thriving Midlands scene. This pamphlet is beautiful, readable, and contains superlative, thought-provoking poetry: it is successful as both an art object and as a literary statement.