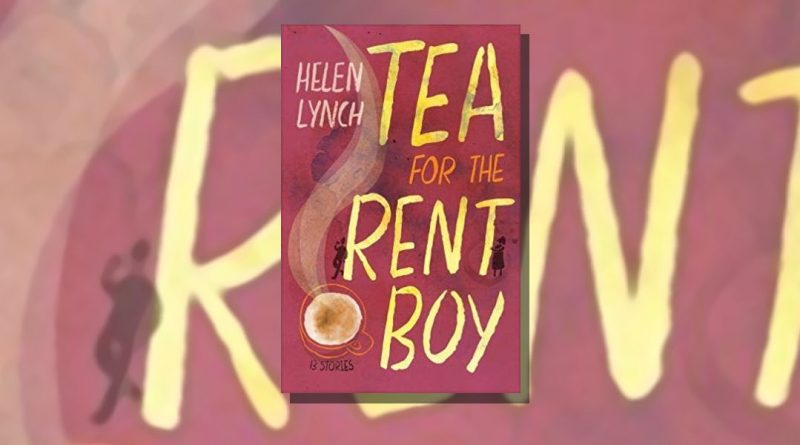

Tea for the Rent Boy by Helen Lynch

– Reviewed by Jenny Booth –

Tea For The Rent Boy, Helen Lynch’s second collection of stories, addresses several weighty themes. One could be feminism and the construction of femininity. Another is history; beneath the surface of most of the characters are complex backstories, geographies and genealogies; a consideration of history not as a costume drama, but a real examination of how we got to where we are. There is welcome attention to motherhood and childhood, sometimes neglected territory in literary fiction.

Lynch approaches these themes by using a variety of voices and styles. ‘Ouenaye at the Post’, is presented as an entry in the journal of a missionary encountering the New World. It recounts the priest’s success in persuading the indigenous tribe he meets that men should rule over women and children should be subjected to corporal punishment. Lynch lets her narrator, confident in his normative righteousness, convict himself. To him, the sight of the tribe’s women punished for rebelling against the new male hierarchy has ‘a comical appearance, as if there had been an outbreak of toothache’; but the description of people restrained with ‘a gag or bridle, stopping their tongue’ is brutal and sad on the page. His satisfaction, verging on erotic, in watching the whipping of one of the girls, is repulsive.

‘Ouenaye at the Post,’ tells the story in microcosm of colonial dominance, and the consequent supremacy of values such as male superiority, female modesty and intolerance of children. In a sense, the legacy of this can be seen as the trap that the collection’s more contemporary stories find themselves in. Nurses restrain a three year old girl screaming for her mother, because she’s a ‘bad girl’ for disturbing a ward of children expected to sleep through the night in silence. A husband who becomes frustrated and cruel when confronted with his wife’s depression is unaware that it is at least partly caused by the fact that being a housewife isn’t fulfilling in the way social convention had led both of them to expect. The teenage girl sexually abused by her grandfather reflects that it isn’t especially ‘unpleasant, simply a rather odd use of my time. But then, what isn’t in those years you spend doing nothing in particular but growing up, when where you go and what you do for so many hours of so many days, weeks and years is dictated by others, determined by forces so arbitrary as to seem inevitable?’

One of the purposes of the writing is to give some agency back to these characters. Some characters manage acts of resistance, but other pieces simply give them a voice and bear witness to the injustices they experience. Lynch is adventurous with the variety of voices she experiments with in the collection. The story ‘Sapozhkelekh‘ is a first person narrative from the point of view of a young child explaining the world as she understands it, recollecting conversation from adult figures that touches on a wide range of topics including genocide and sectarian violence. In doing this, the narrator in ‘Sapozhkelekh’ not only recreates the stories that she has been told, but also gives the reader an appreciation of a young child’s point of view, the ways in which she would be able to empathise with children caught up in genocide, and a sense of her own vulnerability.

If this all seems worthy and issue driven, it isn’t. The prose is often beautiful and deeply atmospheric, particularly in its observations of the natural world. As spring comes to the oppressive suburbs, ‘A furry green softness trickled through the branches of the sycamores.’ A girl dragged along to a house viewing by her parents slopes off to its wild garden to see ‘splayed damson trees, the mound where a wave of ivy swept up over a fallen fence, the hedge brambles sprawling in rusty coils on old rockery stones.’ ‘French Leave,’ a story about a woman stuck in rural France while she waits for an older man she is having an affair with, opens:

‘Last night the barn owl called like a creaking door in the orchard. At dusk I saw it, the great creamy shadow sailing just above the grass-tops between two grizzled plum trees. The mountains glowed. I thought it must rain.’

Reading prose of this quality is pleasurable in itself but it arguably performs another function. It’s important that the landscapes of literary fiction are populated by and seen through the eyes of, Polish immigrants, housewives and curious children.

If the colonial misogyny of ‘Ouenaye at the Post’ is a constraining backdrop to the collection, the title story ‘Tea for the Rent Boy’ offers new possibilities. Its conflict is ostensibly simple, a woman trying to decide whether to make a clean break from her partner. The story approaches this question by exploring the histories of the couple within their relationship and separately, where they came from politically and culturally, hinting at how this has affected them. It also considers the future, particularly in relation to Rosa, the couple’s teenage daughter. Rosa initially appears confident and assertive, apparently oblivious to gender roles. Later in the story however, Rosa is impressed by a display of male violence (when deployed in a cause she approves of) revealing her position to be more precarious. It suggests that the narrator’s choice as a woman in her relationship will have implications that reach beyond her immediate circumstances and leaves the reader wondering which way it will go.

Tea for the Rent Boy is a well written and fascinating collection of stories. It encourages readers to think about how and why things are the way they are, and how things could be better.