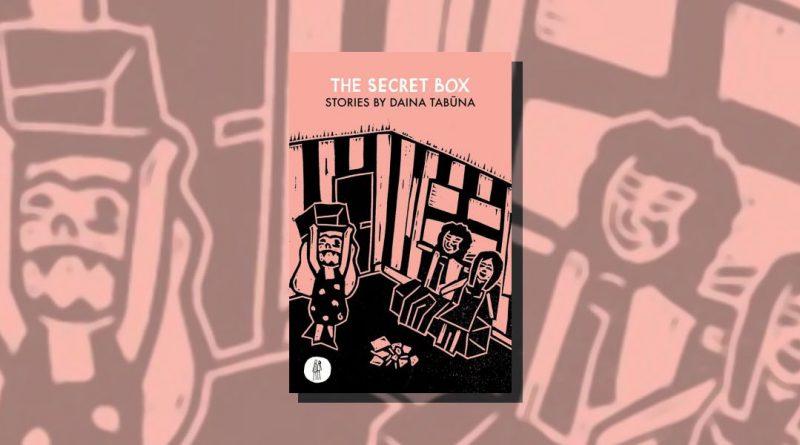

The Secret Box by Daina Tabūna

– Reviewed by Scott Manley Hadley –

The Secret Box by Daina Tabūna is a pamphlet of short stories published by Birmingham-based independent The Emma Press. All of the pieces are translated by Jayde Will, and were originally published in Tabūna’s native Latvian in her award-winning debut collection, Pirmā reize (Mansards, 2014).

Google Translate informs me that Pirmā reize translates as The First Time, and a little bit of research suggests that said collection contains more than the three stories included here. This is frustrating, because there are no other translations of her work and, well, I can’t read Latvian…

All three stories are set in a post-Soviet city at the end of the 20th and beginning of the 21st centuries. Each one explores – to a lesser or greater extent – “growing up”. The “growing up” in question isn’t identical, this isn’t three vague “coming of age narratives”, in fact quite the opposite. Each piece is set within the youth of a protagonist: in childhood, adolescence and young adulthood.

The first story is called ‘Deals With God‘ and offers a unique exploration of a specific cultural moment. The story – told in a childlike first person – follows a young girl as she responds to the 1990s revival of Christianity that followed decades of religious repression under the Soviet regime. A nun begins giving classes on religious doctrine at the girl’s school, and she becomes hooked on Jesus. Unfortunately, the nun retells the Bible chronologically, so by the time the torture and crucifixion of Christ comes up, our narrator’s attachment to him has got to such a point that she is FLOORED. She goes out into the world and tries to bring good in lieu of Jesus, now she knows he is dead (because no one can come back from the dead, right?), but quickly runs against resistance. The story ends somewhat abruptly with the implication that her Jesus-phase is over.

To be frank, as a reader I’m not really interested in discussions of religious faith (though is questioning religion in the voice of a child a statement of secularism?), and I was pleased that the rest of the collection dealt with other subjects. The central themes of the later pieces are more universal and thus easier to emote to, or at least they were for me.

‘The Secret Box’ is a story about a girl on the cusp of puberty finally bonding with her older brother over a shared interest in creating, drawing and playing with elaborate paper dolls. Unsure of her own adolescence and confused by her brother’s shameful engagement with dolls and drawing, i.e. girls’ stuff, she tries to embarrass him by showing his new girlfriend the stories and dioramas and characters they have made together. “I awaited her disapproval and disgust,” she thinks, “I awaited [my brother’s] anger, shame, and denial.” Of course, though, she is wrong:

the teenage artsy girl dating the teenage artsy boy is charmed, rather than appalled, by the evidence of a close, creative bond between her boyfriend and his younger sister, so in a confused, depressive act the sister pessimistically destroys all the paper dolls and resigns herself to the end of childhood and the end of playing.

It’s a sad, moving, conclusion, beautiful both as allegory and as a simple tale of childhood.

The final piece, ‘The Spleen, My Favourite Organ’, is a significant text about a young woman ending up in a sexual situation that terrifies her. As with the two previous stories there is a first person narrator, but this time it is a young woman, rather than a child, though a person not “settled” in the adult world. She is lonely and spends time with an equally-lonely young man, but being together does nothing to change that feeling:

“I concluded from that what I had already anticipated: we didn’t have anything to talk about.”

Eventually, the man begins to touch her in a way that she does not want. The story does not descend into violence, and this is what makes it powerful and pertinent: it is about the social and societal pitfalls that result from unexpected and unwanted male sexual attention, and the repercussions of many people’s inability to discuss openly and directly what they do and do not want. It’s perfectly-pitched, very clear, and deeply emotive.

The pieces in The Secret Box are accompanied by original woodcut illustrations (or woodcut-style illustrations) by Mark Andrew Webber, which tonally match the pieces and are therefore a valuable inclusion.

Perhaps a brief note as to why these particular stories of Tabūna’s were chosen for translation might have been interesting, but maybe this is a concern of a curious reviewer rather than a general reader.

The Secret Box is an engaging, thoughtful and disarmingly varied selection of stories that deal with important topics: there’s a lot in Daina Tabūna’s collection here to love. A thoroughly enjoyable read offering real insights into the many ways that the lives of ordinary people are affected by huge political turmoil. Well worth a look.