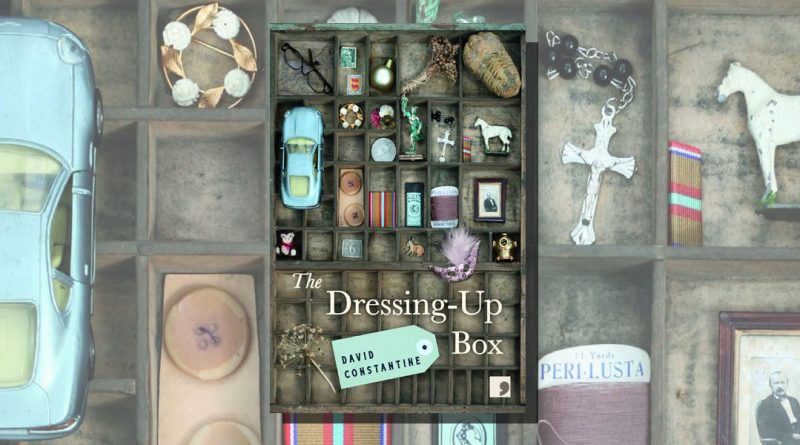

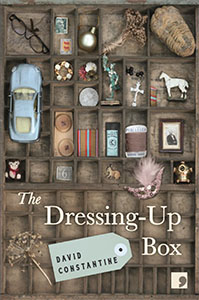

The Dressing-Up Box by David Constantine

–Reviewed by Markku Nivalainen–

David Constantine is a poet-scholar who has had an illustrious career as an author, translator and academic. The wider audience probably knows him best for his award-winning short stories, one of which, “In Another Country”, had a second life as the critically acclaimed movie 45 years. Constantine’s latest collection, The Dressing-Up Box and Other Stories (Comma Press), is a cornucopia of wonders. The stories vary in length, style and subject matter, but certain themes reoccur throughout the book. The story that lends its title to the collection combines these themes in a manner that beautifully illustrates the tension between dread and hope that propels the book.

‘The Dressing-Up Box’ is the story of a group of children sheltering from war in an abandoned house. Part of their schedule includes performing absurdist plays inspired and illustrated by an endless number of curiosities summoned from a dressing-up box. The story is a heart-warming allegory of all that is good in humanity and the importance of the aesthetic in dark times. Their art portrays a world where good qualities are not denied, thus offering some respite from the reality around them while doubling as an imaginative critique of it.

The kindness of the children advocates a view of human nature that is in stark contrast to the questionable but stubborn view grounded on the notion of original sin that was famously bolstered by the Lord of the Flies and continues to prevail in European literary imagination.

The most powerful stories in the collection tread a fine line between the mundane and the fantastic. It is for the reader to decide whether, for example, the dressing-up box is genuinely magical, or do the vast number of things it carries simply make it appear as such to its imaginative users. I found the stories that appear to reject this fundamental ambiguity to be the least successful. To remain understandable, allegories rely on narrow definitions of the key categories they are built upon, and this ends up limiting their ambit. A good example is the wryly humorous and at times painfully grotesque story titled ‘When I Was a Child’ that risks mirroring the morality plays it seeks to deconstruct.

Ambiguity allows for much more flexibility and is one of the defining features of my favourite story, the exquisitely crafted ‘The Diver’ that subtly manages to pare down the entire world of a hefty novel into a mere five pages. The open ending demands the reader to create a past and project a future for the characters that Constantine so masterfully fleshes out with the most minimal means. The lines in ‘Rue de la Vieille-Lanterne’ describing Gérard de Nerval could also be used to describe the author himself:

“You were good at situations and at plots and sub-plots, one thing leading to another. But you were quite hopeless at dénouements. When did you ever bring anything to a conclusion? You were all beginnings and little forays hither and thither. That’s what you enjoyed and that’s what you were good at: inventing situations full of possibilities.” (165)

Constantine ensures the realm of possibilities seem almost unlimited by making both the beginnings and endings of his stories seem arbitrary. Although the events described are essential to the stories, the characters and the trajectories of their lives are not defined by them. In stories such as ‘The Diver’, we are offered a brief window to a world that appears to exist largely beyond the page, and any meaning the story might yield is largely accidental and dependent on what the reader brings to it. This dynamic is prominent in ‘A Retired Librarian’ that has the freewheeling husband of the protagonist question his wife’s desire to find answers to all the questions roused by the strange events that have recently taken place in the neighbourhood:

“The trouble with you, said Sid, if you don’t mind me saying so, is that you feel people’s stories have to make some sort of sense. Whereas in reality it’s all accidents, that make no sense.” (151)

For Constantine, our imposition of meaning on the world through narratives is delimiting and too often used to stifle the richness of life. In The Dressing-Up Box, stories with sense and conclusions are the remit of corrupt clergymen (‘When I Was a Child’) and lunatics (‘What We Are Now’) who understand neither kindness nor innocence.

While death, insanity and horror are present in most of the stories, Constantine nevertheless delivers a message of hope.

The acceptance and kindness of children is, for Constantine, essentially life-affirming and in a heart-warming gesture, it is to them that he dedicates the book.

Find out more about The Dressing-Up Box and Other Stories on the Comma Press website.

Reviewed by Markku Nivalainen — Markku is a lapsed academic and an occasional critic. He lives in Pontyclun, Wales, and provides administrative assistance for the Cardiff University Library.

You can get in touch with Markku via his website, The Unemployed Philosopher: http://unemployed-philosopher.co.uk