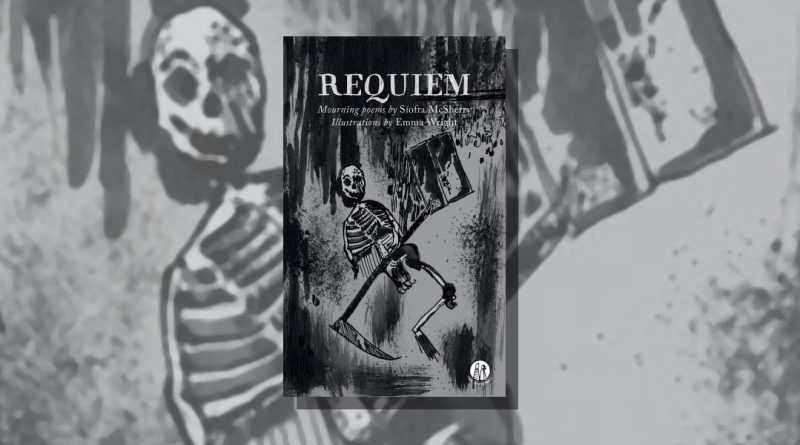

Requiem by Siofra McSherry

-Reviewed by Grace Atkinson-

Written in memory of her mother, who died of motor neurone disease in 2012, Siofra McSherry’s Requiem guides us with nerve and tenderness through a multitude of very human and complex copings with grief. These include the emotional processes we make (from denial, to anger, to sadness) to how we address death (from a prayer, to a legend-like story, to memories shared with a friend). Sometimes death goes unnoticed until, like an unexpected relative, it comes to stay for what feels like an eternity, then drifts back into the periphery. In this sense, McSherry’s pamphlet becomes a guide to what takes place when Death becomes a visitor we are forced to accommodate.

‘Kyrie’ is a poem that plaits transitions like the weaving flows of a waterway, as each stanza drifts from the spiritual [‘Lord have mercy upon her’] into the physical [‘Bed have mercy upon her’], and from the external [‘Catheter have mercy upon her’] to the internal [‘Neuron have mercy upon her’]. There is something both painfully helpless and soothingly dreamlike about asking for mercy from things that are as objective as a needle and as transient as breath; from the very proteins that make and unmake us. The only commonality within the list that makes up ‘Kyrie’ is their inability to respond to the demands made on them and, in a way, the opening two poems of Requiem are like the first phase in a string of changing dialogues, starting with a one-way plea [‘now hear our prayer’].

There are times in McSherry’s pamphlet when we are in the presence of a reciprocal conversation, ‘Pie Jesu’ for example, reads like the call-and-response of a song, the ‘Aye’ of every other line as consistent as waves: [‘Tis a hard road./Aye. And, ‘tis a soft./ Aye, so it is’]. We are not made quite so privy to the conversations in ‘Tract’ but the craic that is ‘spooling nicely’ can be practically heard, as each line rolls into the next, seeming to dart from one corner of the ‘rickety bar-room’ to the other. Like the cutting of strings in ‘Agnus Dei’ silence is made unbearably painful in this book, and in this chaotic and crowded poem the ‘odd unbustling’ of the Faithful Departed is hushed into silence as Death enters ‘with/ little warning but a rash of goose-/bumps’, leaving us only with an awareness of the long wait.

Often stories and anecdotes become tools to re-live moments with those lost, and ‘Communion’ clutches at the memories of someone who is slipping from them [‘I’ve already lost your voice and most of your face’]. But, in this poem, the power of an anecdote becomes double-edged, both able to conjure memories of the dead [I used to think you sang too loudly in church] whilst, in the same breath, illuminating what can never be made accessible [You starred as a young woman in My Fair Lady but I never heard/ you sing it], the line break focusing us on the word ‘hear’. One thing that McSherry does so successfully in Requiem is translate emotional conflicts like these, and the last stanza of ‘Communion’ illustrates so beautifully the helplessness of trying to summon someone in a language that isn’t quite your own.

These human contradictions are best portrayed in the humour that sits in the belly of Requiem, with the Real-Housewives-like drama between Death [‘A melancholic fellow’] and Orpheus in ‘Tract’ – [‘Orpheus got drunk and lost his/grip on the subject entirely, later/ being ripped apart by women’] or in David’s coke-induced foreseeing of Judgment Day in ‘Sequinta’. McSherry points at the bizarreness of our everyday ability to ignore, and even deny, death’s tyranny on existence. The speakers of ‘Benedictus’ seem only mildly irritated by Death’s visit, fixated on his disruption of the ‘symmetry’ of their lives, or on how the black of his borsoloni clashes with the earthly hues of their coat rack – [‘kingfisher,/ cream, suede, and emerald green’]. Denial is often depicted as an inevitable stage of dealing with death, but this poem laughs at any pretense made in treating life like a maths problem that can be solved [‘the geometry of the house changed’]. No matter what we do, death is the only possible answer to life.

In ‘Sequinta’, McSherry attempts to undercut God’s cinematic wrath with this same humour, and as He scrawls the sins of the world across the sky (reminiscent of looking at a phone for too long before bed – [‘we close our/eyes but see it scrolling still, in black on lidden red.’]. He lists a history of very dull but funny wrongdoings – [‘Mullen cheated on her husband, June of nineteen/ninety-four. Muhammad on the second floor/stole his neighbours’ WiFi’]. Meanwhile, Death is depicted like a character from Kevin Smith’s Dogma, [‘Death sits and/pours himself a double shot of rum, and sighs. This fucking guy.]. In films, in the press, and in the stories we tell each other, humanity has always made their own narratives around Death, perhaps in an attempt to shake its existential grip. McSherry places herself amongst the performance of a ‘hundred million trumpets’ [‘Crawling and weeping. I drag myself into the light.’] and we are caught up in the horror.

From the piercing directness of McSherry’s final poem ‘At first/there was just the fresh soil and a white cross/and the yellow circle of your wedding ring we forgot/to take from your finger when they closed the box’ to the soft clarity of ‘Libera Me’ ‘I remember that I love’, Requiem is a dazzlingly delicate yet painstakingly thorough working of what it means to lose someone dearly loved. But McSherry also harnesses something shared in her experience of death, which transcends the book into something we could all take guidance from.