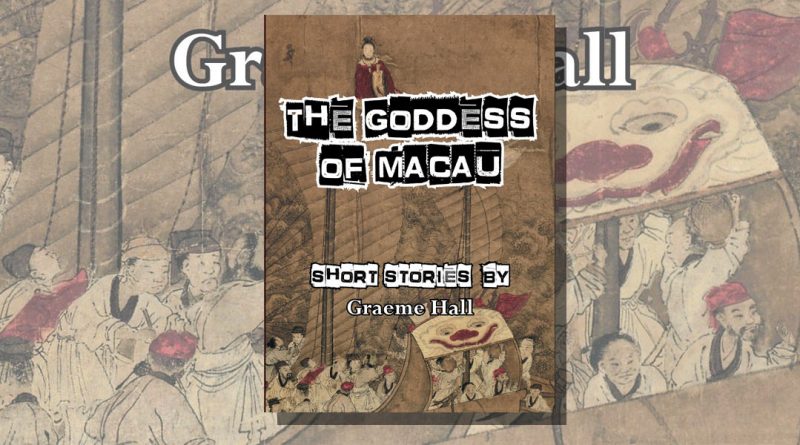

The Goddess of Macau by Graeme Hall

–Reviewed by Ben Cassidy–

When crafting stories, it is vital to consider whether the chosen form is going to be the most arresting, and best-suited, for what needs to be achieved. Graeme Hall is certainly aware of this in his collection, The Goddess of Macau (Fly on the Wall Press, 2020). Choosing to use the “shorter short-story” is a masterstroke. Of course, that alone isn’t going to pique a reader’s interest, it is how the form is negotiated.

The first line of the first story, ‘A Short History of Chinese Tea’, gets the whole collection moving. What seems a simple line, “Today I am meeting my husband for the first time”, is deceptively simple. Only a writer who knows what they’re doing can achieve this with ease and poise. The action has begun. Essential in a piece as short as this. The initial hook, there. What will the experience be like? What will he be like? Basic story-telling skills. What really elevates the line though is that it’s written in present tense.

Readers are right there, with the narrator. They’ll experience it first too. There’s more, though. The whole collection is very much grounded in people and their interactions. Moments of their lives, but the big moments.

The themes Hall will go on to explore in his stories are set out right there. A couple of paragraphs in and this is bolstered by a line that builds essential characteristics of the world he’s created, as “Hushed conversations partly overheard behind closed doors” perfectly illustrate the central character of the story spying on her own life. But only with the follow up line “I don’t mind”, is the nature of the subjugation of the women he creates really revealed. Hall captures the complicit participation of the victim, and her acceptance of her lot. Only through knowing a culture so well can this level of sensitivity be attained.

A book that springs to mind that can perhaps help best understand these stories (from a Western perspective), as well as the significance of their setting, is Edward W. Said’s Orientalism (1978). Said claimed many works that attempt to capture a culture are, when written by a western or European author, only capable of being biased and romanticised. In short, propaganda, whether intentional or not. Hall’s works are very much written in celebration of a culture he’s taken time to come to know. His handling of their strength and identities shines through in lines like “The men are tired”, from the second story, ‘All Will Be Well’ and one following, shortly after, “One more big one, that’s what we want”.

Their dreams are their own. They are hardworking. Such representations help to dignify them, providing a well needed antidote to the tired Western view of Asian cultures. Especially those who have repeatedly had their agencies removed via stereotyping as lazy or incapable, requiring the West to let them prosper.

In ‘River Crossing with Night Herons’ what really begins to show is Macau’s uniqueness. As well as having been a territory of the former Portuguese Empire, and so subject to their Colonialism, the Communist Regime of China has also heavily influenced their way of life. “Each day had been marked with public denunciations”, writes Hall, before adding that:

“The schoolmaster had been first, forced to admit that he had been teaching George Eliot. The Shopkeeper was accused of cheating his customers by leaning on the scales when he weighed out the rice”.

It’s here that the reality of life is shown. Whilst Macau was officially a Portuguese protectorate until 1999, it’s what happens there day-to-day that is of interest to Hall. The actual lived experience of the inhabitants and what they face. He really manages to put in concrete terms the ways their lives and state of existing are managed by those in power. This culminates in his telling how “One farmer was blamed for the drought […], another for the flooding”. A sense of what life is like against ideologies of such charged aggression and perpetual oppression conveys how authority works.

Constant struggle and desire for simple freedoms is elegantly captured in the final line of the story, as “I hear once again the deep, raspy caw of a night heron”.

Other themes in the collection are love, loss, loneliness and sometimes just survival.

A sudden switch to the supernatural brings great results in ‘An Apartment on Coloane’. The story is narrated by a fortune teller who provides the revelation “The thing is, I’m actually the real deal. Not one of those fakes or tricksters that prey on people”. This self-awareness of the character’s own condition doubles as a pronounced example of mysticism, that exposes the Western-centric view of many readers that accept such traits. Hall takes a stereotype and breathes new life into it, using it as a way to dig deep into what most drives people. His story about death makes the supernatural natural, and so also one about life. Towards the end of the tale, Miss Choi, who has come to visit the teller, reveals she too can see. The narrator states “She’ll need to keep a sense of detachment”. Like the powers being discussed, the reader is offered only a glimpse of the future. Miss Choi will live, but life will be hard. Carving out such bonds between character and reader isn’t an accident.

‘A Photograph Creased’ deals with difficult relations within families. The old, the young, the often-terse pacts between the two. The fragility of relationships is another recurring theme through the collection. Hall sums this up well in the line “Why did they lose interest? Did you say something to them?”, perfectly outlining the damage words can do, from speaker to target. Connotations of blame and pressures of expectation are summoned here, with devastating simplicity. Hall goes on to show that that words alone don’t make for highly charged emotional encounters. Towards the end of the story, despite the fact that the narrator speaks only a little English, what’s still apparent is that “I can sense his disappointment when he realises that I don’t understand”. This is truly the language of a writer. Hall captures something of the animal, the instinctual, that thing unspoken but that’s the loudest in the room. The psycho-emotional bond an interaction can have. He shows how they breaks down all barriers.

Two of Hall’s later stories in the collection are connected by the same character. ‘The Price of Medicine’ and ‘From Somewhere the Scent of Jasmine’. It was pleasing to read more of Mei-Wa, in the latter of the two stories. Almost as soon as you’ve started to get to know these characters in Hall’s world of Macau, they are gone. His stories are very much sketches, outlines of larger lives. ‘The Price of Medicine’ is about a young woman who enters into prostitution to get the money to help her sick mother. As soon as we hear that “Throughout the night she tried to ignore what was happening”, we know that things won’t end well, whether her mother gets the medication or not.

Later, in ‘From Somewhere the Scent of Jasmine’ (the final story in the collection) when we hear her say “I had business to see to, I told you that” we realise she didn’t end the prostitution. The line takes on further power because it’s spoken to her father. By the second story a very different, hardened version of Mei-Wa is born. Perhaps it’s motherhood that’s responsible; that, and the pressures of also trying to look after her ailing father’s health. The way she talks to him, views him perhaps, is different from in ‘The Price of Medicine’. At the end of that story “She wondered when would be the best time to tell him that she was pregnant”.

Something crucial to conceive, for any writer hoping to use the short story to powerfully effect, is the need to make an impact with what is not written, as much as what is. The penultimate story, sandwiched between the two connected pieces is ‘The Jade Monkey Laughs’. The economical line, “They’ve been there longer than she has worked for Senhor Almeida”, deals in multiple aspects of the story, simultaneously. On the surface, the line is about a statue of jade animal – the monkey in the story’s title. But the line is also talking of the character’s relationship to the object; and the many years of her life we don’t get to see. We soon hear that “It was ten years before she was even allowed in this room”. Here, we really get to understand things, as Hall musters the distrust and growth of status of the character, by her employer. Simple lines, but important ones. Further evidence of Hall being accomplished with the form.

What comes through overall is that Hall writes all of his creations into the history of Macau. He offers snippets of fuller lives, managing to remind us that we all judge and stereotype, based of limited information. Hall is aware of this and consciously seeks to avoid the trap. Giving these characters a complex and personal history makes them important as individuals, as well as symbols of their homeland and culture.

He knows that the place and people can never be separate from the regimes and processes that have brought them about, but that they do exist apart from both. They belong to neither; thanks to Hall, the people in his stories have a sense of belonging to themselves. They matter on their own terms, not just as products of politics and power-struggles. It’s obvious that some of the place is living through him, and has captured his heart like no other place quite could. What he manages to do, is give you glimpses of why, allowing your heart to see some of what his has, so diligently and respectfully. Vitally, Hall’s stories make you want to look into yourself, as much as into the characters and their settings.

Find out more about The Goddess of Macau on the Fly on the Wall Press website.

Reviewed by Ben Cassidy — Benjamin Francis Cassidy was born in Blackpool, in 1982. He lives in Manchester with his cat, Lucy, where he gained his Degree, from Manchester Metropolitan University in 2018, in English and Creative Writing. Non-fiction work includes publishing by Louder Than War, Sci-fi Pulse, Mad Hatter Reviews, and Fly on the Wall Press’ Blog. His fiction appears in two new writer anthologies by Comma Press. Ben writes poetry too and has poems published by Fly on the Wall Press and Yaffle. All his work attempts interpreting what he feels is a very strange world.