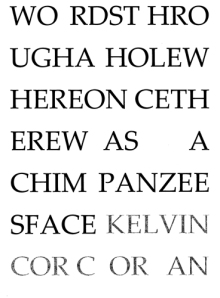

‘Words Through a Hole Where Once There Was a Chimpanzee’s Face’ by Kelvin Corcoran

-Reviewed by Afric McGlinchey–

Kelvin Corcoran has already published eleven collections of poetry. But this Longbarrow Press chapbook is really ‘an intimate work for a few friends’ he tells us, obscurely, in broken-up words. The title is also portrayed as a scrambled series of letters on the cover, which, in itself, is a striking image. The dedication reads: ‘For and from…’ followed by twelve names, all of which are mentioned in subsequent poems. So it’s with a sense of voyeurism and intrigue that the reader (who happens not to be one of those named) approaches the poems.

Part 1 is titled ‘Going Down’, and down we go, with the narrator, into the abyss. He finds himself, after a stroke, among ‘the blurred and breathless dead’, the only thread connecting him back to reality being ‘you / sifting through my hands – a shadow’. The impact of the poems accumulates as meanings are unscrambled. The title symbolizes the narrator’s mind which is hallucinating, seeing noises, being invaded by colours. He touches a mouth, a nose: ‘This is your face isn’t it?’ he asks his lover. The title comes from a second-hand book, The Wonder Book of Wonders, sent to him by a friend and from which, on p.88, ‘someone has cut out the face of the chimpanzee’. When even the face of his loved one is insubstantial to him, this absence is all the more alarming. Through the hole, the narrator reads random words:

wet season

most for

animals earth

Herr Forelegs

These words acquire a resonance for the poet, and act as a springboard for many of the subsequent poems. He uses prose to give the reader some context: ‘I was blind and suffered some short term memory loss because that area of the brain was hit by the blood clot’. But I wonder if explanation in an otherwise lyrical collection is really necessary.

‘Herr Forelegs’ becomes a human entity, ‘a lurking confident bastard / his shirt of bloody platelets / his heart like a fist – bastard’. The tone of the poems swerves from bewilderment to hostility, to a dark humour: ‘come on you anti-coagulants – take these chains from my heart and set me free’.

In one sense, The Wonder Book of Wonders takes him out of his own terrifying mental experiences, to focus on external images: ‘A man in a weighted diving suit, / acetylene torch in hand makes wrecks fit to float’. This of course suggests the resurrection of his own physical and mental wreck of a body.

Other outside influences, such as music (a motif throughout the chapbook) penetrate his altered state: ‘John Coltrane bends time / Bach straightens it out again’. But Herr Forelegs continues to haunt him: ‘in the crowded darkness, you belong to me,’ he says.

His friends call and email, and Herr Forelegs calls too: ‘with eyes for inner darkness: the shit’. Here there is a little too much telling, when simple showing would do: ‘Andres called, his voice / his restorative conversation’. There is an echo of Frost when ‘Goldberg skips decorous sprightly / along the neural tracks, / down the digital wood dark and deep’ where ‘light walks through the trees’. And we remember, ‘I have miles to go before I sleep’. Corcoran blends nature images with technology in a number of poems:

‘These trees look designed,

them birds is on fire

in loops and swirls the sky ablaze.

A radar script inscribed

what does it say? what does it say?

the word as non-conductor of electricity’

In ‘He stared at death. Death stared straight back’, Corcoran writes:

‘MRI shows the riot here and here,

let it rip, Elijah, roll us in our boat;

phosphor trails a migrant route’

but moves from this bravado to sincerity when addressing his lover:

‘Did you fear I could leave you so easily…?

…I would see you leaning over me, your dark hair,

your eyes stare down burning

like the first night we spent ourselves on each other.’

Poems are connected by motifs: boats (the journey, salvage), animals, words, numbers, faces. The narrator slowly begins to return from ‘katabasis’ (from the Greek, meaning retreat or descent) when he realizes that:

‘there’s no shape for me out there if not you,

our days like silver boxes open in our hands.’

Part 2 is titled ‘Coming Back’, and in the first poem he sets out on the journey to recovery, observing the external world: ‘Three women walk down the street / red coat, black coat, something else coat’. Still very susceptible to the surreal effect of stimuli, colours pulse into the narrator’s consciousness: ‘an unknown yellow world…lettering the sky;’ ‘a square of yellow light;’ ‘a man in a red t-shirt’. The narrator continues to struggle to get a grip of reality: ‘I think I taught that girl, worked with that man, but…not in the world’. Still, ‘that my legs hurt tells me I’m coming through’.

A sense of wonder and awe touches the narrator, as he becomes aware of his surroundings again and begins to recognize people: ‘To walk away from all of that / and to say I know you, I know your names’. Surreal events still occur, however. In ‘Eight Things About The Arctic’, ‘the faces of tourists rip and fly over the white hill’. In the next poem, he seeks ‘the source of chill in my bones; and says ‘leave me here where nothing moves…empty and endless for the mind to lodge at zero’. Letters and numbers surface frequently in these poems: ‘a language holding low around the edges of the world;’, ‘random numbers’ that are uttered aloud, ‘twists of light’ that ‘letter the air’.

In the last few poems, Corcoran moves the landscape several times, from the freezing Arctic to the warmth of Greece. In previous collections, he has drawn analogies from Greek mythology to universalize his themes, and does so again here, linking his personal journey with the story of Odysseus. The poems are narrated in different voices, with threads connecting to the first part of the chapbook: ‘I poured my heart into a hole in the air’. These are polished pieces, but their inclusion here is possibly a little self-conscious, the style and tone quite different. All in all, however, this collection is a fascinating journey through several mental states, worlds and weathers until finally it is love which brings him back from the brink: ‘the only thing to hold onto at the dark door.’ These poems reflect a voice that is assured and sometimes refreshingly original.

The collection does indeed sound fascinating. Great review. Thanks.