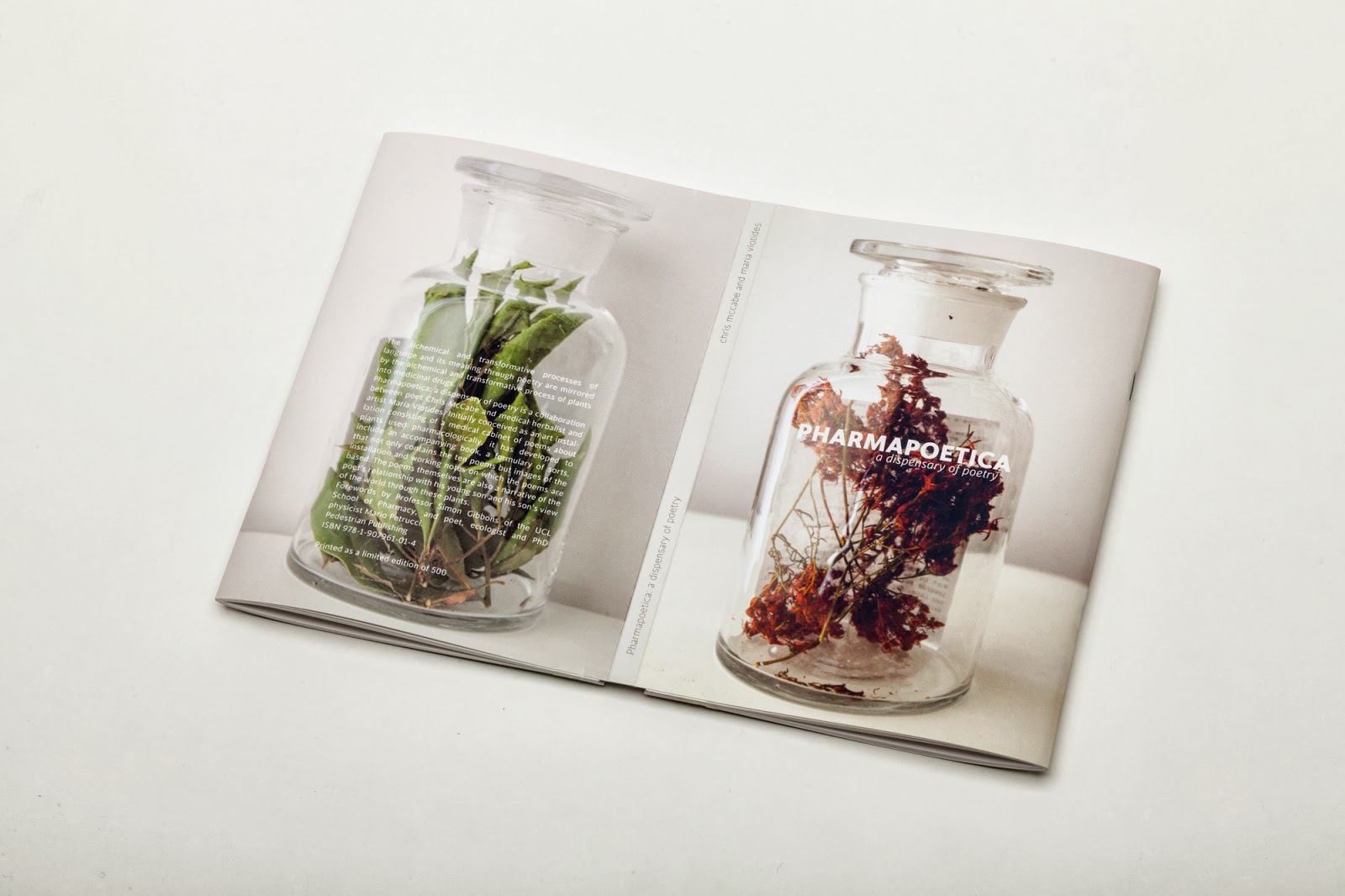

Pharmapoetica: a dispensary of poetry by Chris McCabe and Maria Vlotides

-Reviewed by Afric McGlinchey–

This unusual and beautiful book is the product of a collaboration between the poet, Chris McCabe, and Maria Vlotides, artist and medicinal herbalist. Initially conceived of as an art installation, the project has evolved into a book containing images of Vlotides’ notes on the herbs, as well as images, and McCabe’s poems. For this project, McCabe escaped to the Cornish coast with his wife and four year old son, referred to as ‘the Boy’ in this chapbook. His decision to write his poems via ‘the hunting gaze of his own young son’ as Vlotides puts it, contributes to the poems’ emotional centre of gravity, which elevates the whole chapbook to become a physical, magical touchstone. In making his son a kind of Everyboy, he universalizes him, so that readers can relate to his activities and observations, and to the parent-young child bond.

In Mario Petrucci’s sensitive, insightful introduction, he highlights McCabe’s particular gift which is to ‘tap down into deeper soils of experiential investigation and association.’ It’s the associations which create the magic. Daisies become ‘SM58 microphones, yellow,/the one-two sound-check explodes in white/word fronds’. He plants fennel seeds and the Boy waits for jellybeans to grow. While observing bay leaves, he discovers that ‘writing is a way to eat yourself.’

Les Murray, in an interview, writes: ‘We have three minds, I reckon, one of which is the body, while the other two are forms of mentation: daylight consciousness and dreaming consciousness […] The questions to ask of any creation are: What’s the dream dimension in this?’ McCabe immerses himself in all three dimensions in the making of these poems. ‘I’ve been in dreams all day’, he writes in ‘Rosemary’:

‘The Boy says: “Next time you see a circus

just knock it down”.

Sea-spray, my memory; sea-dew my eyes.’

The herbs are not always overtly discussed, but appear in the poems obliquely, like a ‘Where’s Wally’ cartoon: ‘I’ve hidden the fennel seeds in my poem’ he tells us in ‘Fennel’. Sometimes, the reader is offered a gift directly: ‘I offer this antioxidant to your anxieties / as a cardiac tonic for winter deliriums’ (‘Hawthorn’). McCabe draws on the notes given to him by Vlotides, who writes of the hawthorn: ‘A member of the rose family (it also has thorns, hence hawthorn) – rose having an affinity for the heart – these plants are indicated whenever the heart is affected whether physically [….] or emotionally.’ We also discover that hawthorn is linked to death and it’s a taboo to bring it indoors.

As well as allowing the reader observations of his son, McCabe offers starkly intimate revelations of his own, as in his poem, ‘St John’s Wort’ where we are reminded, ‘the mind has cliffs’.

The combination of science, nature and imagery is an intoxicating concoction:

‘Elderflower’s in the cider. 4% pollinated

with hoverflies & sulphites it attracts

surfers saturated with sand & alcohol for

the summer months.’(‘Elderflower’)

A natural poet herself, Vlotides describes in her notes why she included daisies: ‘What really brings lawns to life, other than picnics, are the constellations of daisies that turn a green space into a reflection of the night sky’. There’s a link also between the Boy’s explorations and her own childhood discoveries: ‘I was astounded to discover as a child that each tiny yellow speck in its yolky core was in itself – botanically speaking – a flower, with its own male and female gonads. I was amazed that the simplest-looking of flowers was in fact an orgy of reproductive possibility.’

Physically, the book is a work of art in itself, opening out in both directions, effectively to form two books, one with poems, the other with images and notes. The paper is heavy, and the poetry section only has poems on the right-hand pages. All that white provides a space for each small poem to be seen as a precious gift.

Vlotides’ initial conception of the piece was to achieve ‘an interweaving of science, art, language, memory, the personal and universal: distilled and dispensed’. McCabe has used the resources she offered, the context of location and the presence of his son to produce ten poems which are startlingly arresting and varied. They begin in delight and end in wisdom, as Frost suggests the best poems should. McCabe is a natural aberrationist, giving way to undirected associations, from one chance suggestion to another, in all directions. But the theme keeps him on a steady course, in the same way a piece of jazz keeps a signature baseline. Each poem offers a little wildness and at the same time, fulfils us just as a glass of well water quenches a thirst.