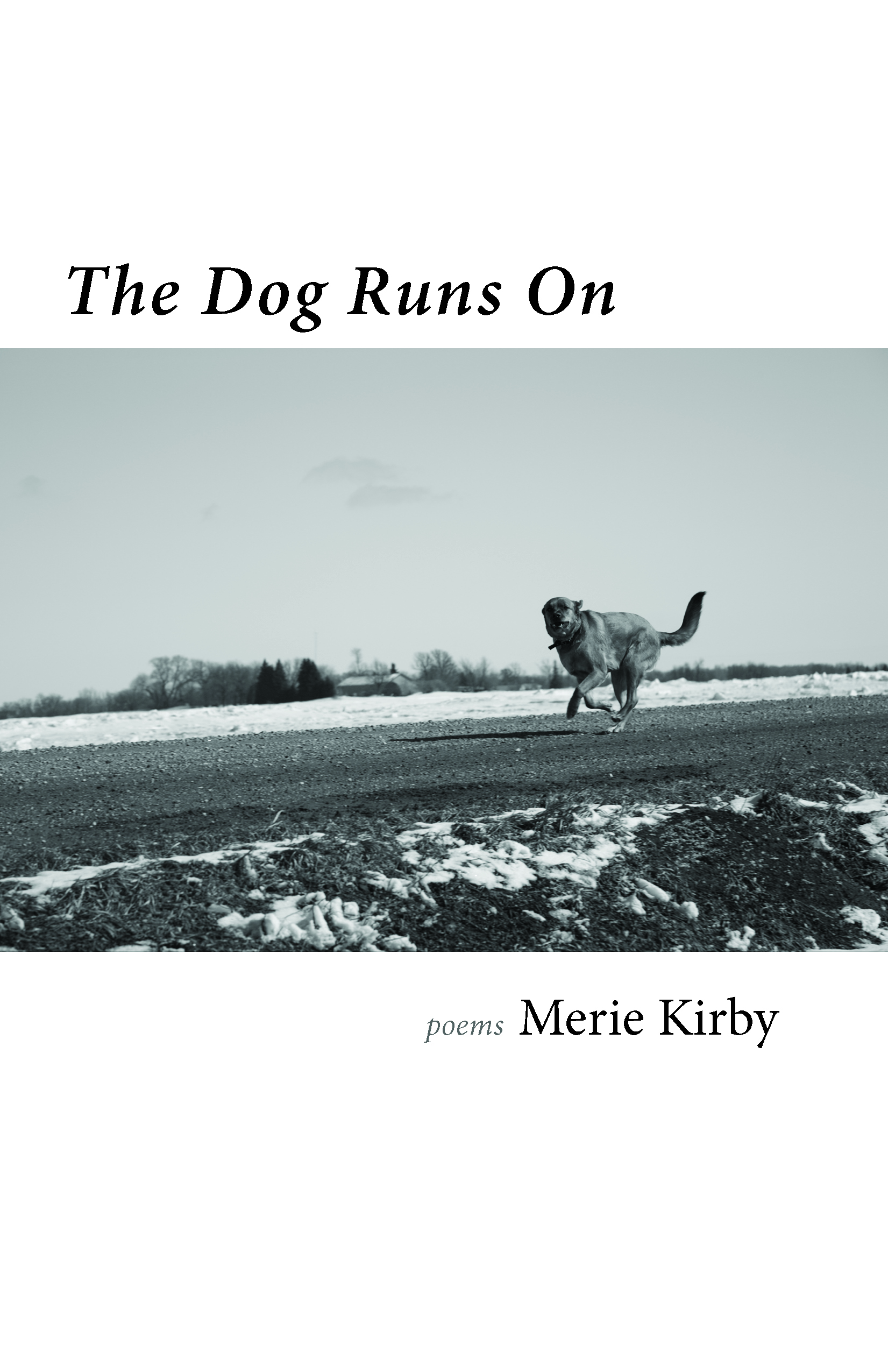

The Dog Runs On by Merie Kirby

-Reviewed by Bethany W. Pope–

Merie Kirby’s first collection, The Dog Runs On, is a fascinating discourse that centres around what it is like for a poet to look at the cruelties of the modern world through the warped crystalline lens of myth, and the ways by which repetitive violence can render even the kindest, most sensitive people callous to the suffering in the world. ‘Sunday morning’ highlights this nicely. In this poem, the media is meant to shock, not inform, and each bloody repetition adds another layer of skin to the poet’s mental nerves, deadening response until:

You’re less moved

than if it were a nightmare

you just woke from.

It takes something stronger

to wake you each time.

It’s not only adults who are damaged by the media-drenched culture we live in; children are too soon inducted into our culture’s voyeuristic cult of horror. ‘When the kind girl grows up’ opens with a shotgun blast of fairy tale imagery reminiscent of the transcendent work of Helen Ivory:

There were the fairy tales, of course, the fire-hot

shoes, the pecked out eyes, the sliced off

tongue, the horrifying stew, the finger flying

through the air – that world where sweet words

are rewarded and bullies end up with a mouth

full of burning ashes…

But these satisfyingly moral tales are wiped from the speaker’s daughter’s consciousness by exposure to the darker, bleaker, world of ‘News’:

She asks, in the car, at night, in the dark

between restaurant and home,

Have any kids died or killed themselves this week?

and later her worried father draws me aside

Where did that come from?

The poem ends with a bitter, cutting revelation as the poet remembers being ‘confronted continually with evidence / that fair may only be another word for pretty.’

This collection is remarkably strong, but it is not perfect. Kirby’s style ranges from concise fifteen-line free verse poems to sprawling experiments in narrative and it is in the later field that the poet exposes her few weaknesses. ‘Ashes, ashes’ was conceptually very interesting, dealing as it does with the magic of growing up and the darkness that hides inside of nursery rhymes, but it would have been much more effective as a prose-poem or a piece of flash fiction:

For her

the most interesting part is that the rhyme is magic:

she can sing certain words and her mother will spin with her,

then drop to the kitchen floor laughing, and let herself

be pulled up to do it again, while dinner bubbles merrily on the stove.

Let me be clear. The writing in this collection is universally good, but this poem would have been more effective if the poet had given in to the urge to write in paragraphs and not inflict line-breaks on writing that wanted to be prose.

Kirby has more success with ‘When I think of genocide’, a prose-poem that uses tight, brutal paragraphs to create breathtaking bursts of ideas and imagery:

When I think about genocide I think about landscape, how it doesn’t matter. I think about religion and how it doesn’t matter. I think about the borderless globe viewed from outer space and how that does not matter. When I think about genocide I think about how hate and politics meet flesh and rend it.

This collection thrums with life; the poems in it are beautiful things united by quality and theme. I look forward to Kirby’s second collection. I am certain that it will fulfil the promises given by the first.